Few films help explain why the cinema of the 1970s still feels so difficult to surpass, as Chinatown does, to the point that it is prominently cited in the documentary about 1975 currently available on Netflix. Not simply because of its formal rigor or the rare convergence of talent behind it, but because the film is rooted in a real problem — historical, urban, political — and finds a narrative form capable of exposing that problem without ever simplifying it. Chinatown does not promise justice, nor redemption. It offers understanding. And it makes clear that understanding comes at a cost.

In Hollywood, however, every canonical work carries an almost inevitable temptation: extending its life through sequels, remakes, or prequels. In the case of Chinatown, the sequel failed — The Two Jakes (1990), the only film ever directed by Jack Nicholson — and the prequel, developed since 2019 by David Fincher and written by Robert Towne, remains in pre-production. Technically, it is still a possibility rather than a certainty. Editorially, though, it reveals something far more interesting: Chinatown was never a closed film.

Where Chinatown came from

Robert Towne’s starting point for Chinatown was never “to make an elegant noir.” Towne wanted to write a detective story anchored in a structural crime; something that could not be solved by identifying a single culprit. His reference point was the real history of California’s water wars: the diversion of water from the Owens Valley to fuel the expansion of Los Angeles, orchestrated by powerful men who enriched themselves by acquiring land and water rights while entire communities were sacrificed.

Turning this into a narrative was the central impasse. Water, land, infrastructure, and administrative decisions do not naturally lend themselves to classical suspense. Towne spent years rewriting, failing, and stalling. The solution was to shift the focus: instead of explaining the system, place a character inside it and follow his gradual loss of control.

The detective as a limit

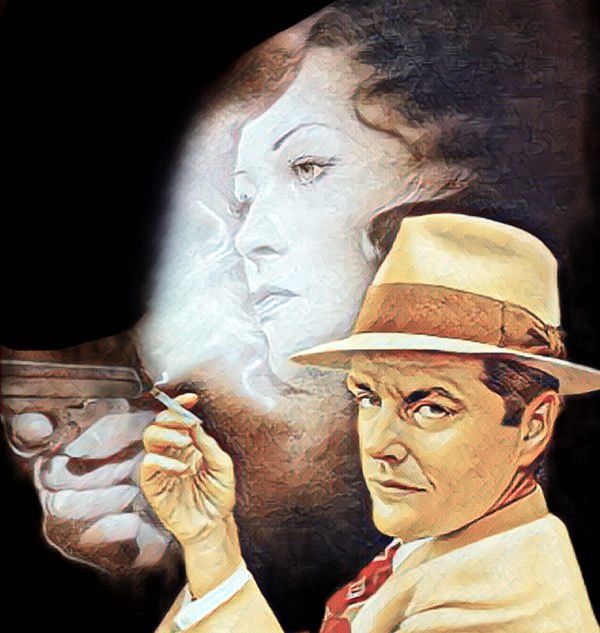

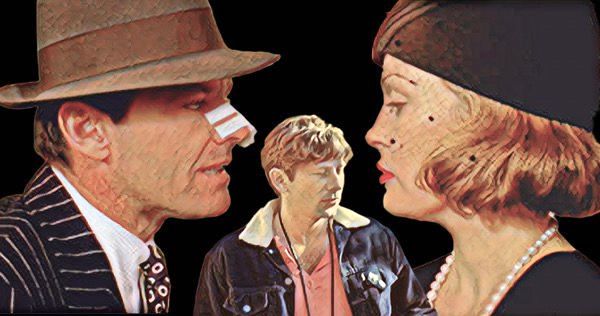

Jake Gittes enters the story believing he understands the game. A private investigator specializing in adultery cases: elegant, witty, self-assured. Jack Nicholson constructs Gittes as a man who trusts his reading of people and his own intelligence. It is precisely that confidence that the film proceeds to dismantle.

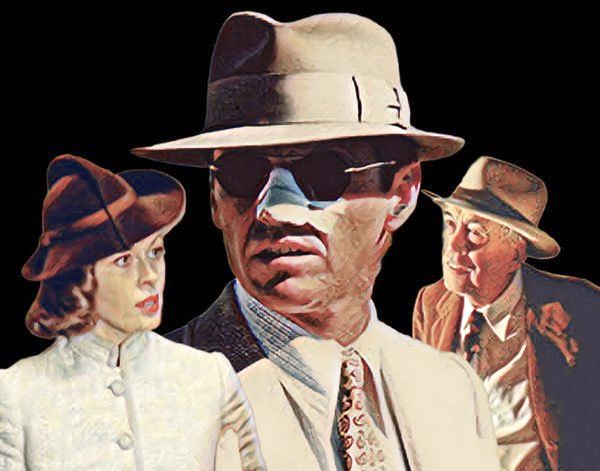

What begins as a small case — tailing a public official suspected of infidelity — expands into a web of interests involving water, land, old money, and political power. Each discovery does not bring Gittes closer to justice; it only reveals how irrelevant he is in the face of the system. Chinatown is not about solving a crime, but about learning the limits of individual action.

Los Angeles as a city without memory

Towne always described Los Angeles as a city of transients — a place where people arrive to start over and erase the past. This is not a sociological aside; it is the film’s dramatic engine. Crimes like those in Chinatown can only thrive in a city without a strong collective memory, where violence can be normalized as progress.

Water becomes the perfect symbol of this logic. Transparent, vital, apparently neutral — yet burdened with violent decisions and private interests. The film turns infrastructure into narrative and makes the city not merely a setting, but an accomplice.

Polanski’s rigor

Roman Polanski’s arrival is decisive. His most important choice is not aesthetic, but structural: the film never abandons Gittes’ point of view. The audience discovers things when he does — never before, never after. There are no parallel scenes offering moral advantage or external explanation.

This rigor creates a particular experience: we follow the protagonist and, at the same time, are trapped by his limitations. Noir ceases to be merely a style and becomes a way of seeing. Knowing does not mean being able to act.

Evelyn Mulwray and the tragic core

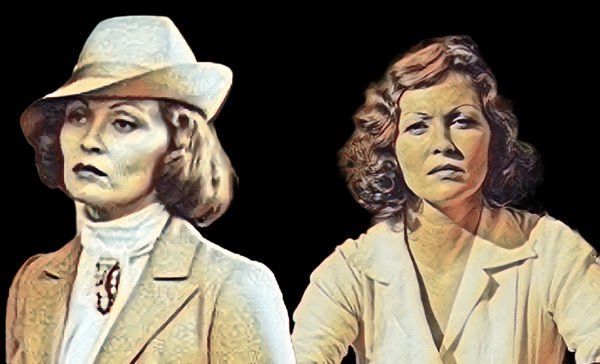

When Evelyn Mulwray appears, played by Faye Dunaway, the film leans on the classic expectation of the femme fatale only to subvert it. Evelyn is not manipulative; she is someone trying to survive within a system that crushed her from the start.

The revelation of incest — one of the most disturbing in American cinema — does not function as a gratuitous shock. It lays bare the film’s central theme: power that invades every sphere, including family and body. Evelyn is the only character who attempts to interrupt the cycle. And she is eliminated for it.

Noah Cross and the permanence of power

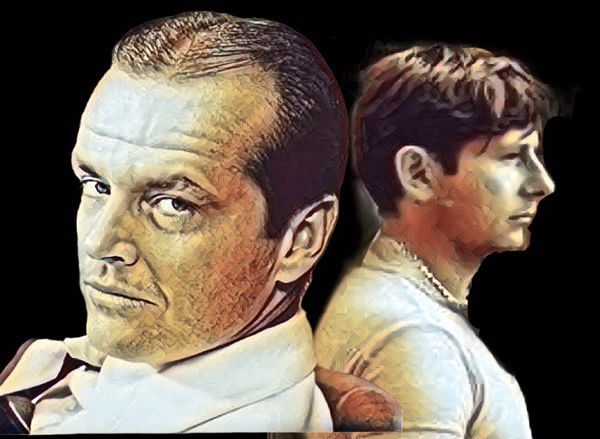

Noah Cross, played by John Huston, does not behave like a traditional villain. He does not hide, explain himself, or fear consequences. He represents power that sees itself as natural, hereditary, and inevitable.

When Cross goes unpunished, Chinatown articulates its harshest thesis: systems do not collapse when exposed. They adjust and keep operating.

The ending that had to exist

The finale set in Chinatown was a point of conflict between Towne and Polanski. Towne imagined an ending just as bleak, but more elaborate. Polanski insisted on something simple and dry. Over time, the screenwriter acknowledged that the director was right. After such a complex plot, the film needed a direct, almost banal conclusion.

“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown” is not irony. It is a diagnosis. It recognizes that there are spaces where the logic of justice does not operate. And it remains one of the most iconic lines in cinema.

The sequel and the stalled trilogy

Towne once imagined Chinatown as part of a broader arc about the corruption of Los Angeles across the twentieth century. The sequel, The Two Jakes (1990), written by him and directed by Nicholson, shows Gittes in 1948: older, comfortable, integrated into the establishment.

The reception was lukewarm, the box-office result disappointing, and any plan for a third film — sometimes called Gittes vs. Gittes — was abandoned. Not because the idea lacked legitimacy, but because the definitive film had already been made. Repeating Chinatown proved impossible.

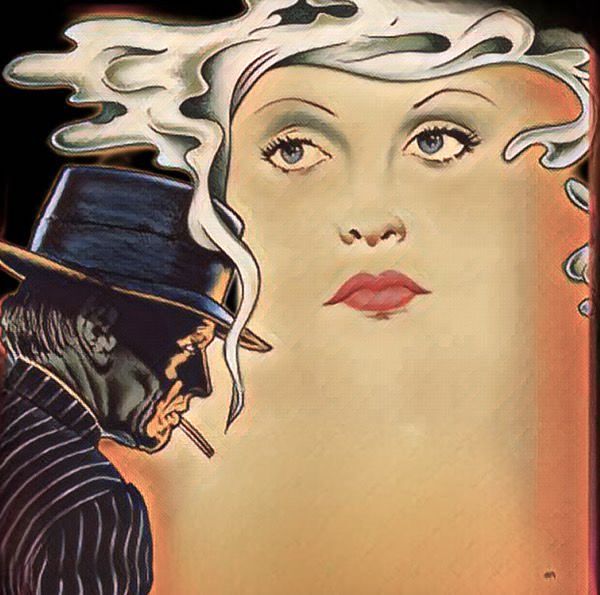

Why Chinatown is one of the great noirs

Because it understands that modern evil is not spectacular, but administrative. That corruption works best when it is efficient. And that truth alone does not guarantee repair. Chinatown redefines noir by stripping it of any promise of comfort.

Its influence stretches across decades of political thrillers and conspiratorial narratives. It does not imitate classic noir; it pushes the genre to its logical limit.

David Fincher’s project

It is within this context that, in 2019, the prequel project developed by David Fincher with Towne for Netflix emerged. The proposal is not to revisit the film’s mystery or repeat its villains, but to follow a young Jake Gittes, still believing that method, ethics, and intelligence are enough.

Towne confirmed, before he died in 2024, that the scripts were written. Netflix’s silence does not invalidate the project; it merely underscores how uncompromising it is. This is not about expanding IP, but about deepening an idea: that there are systems that teach their limits early — and decisively.

A film that remains active

If Fincher’s Chinatown project has yet to move off the page, the original has not aged because it never offered easy solutions. It remains current because it describes a mechanism we recognize, not as nostalgia, but as a reading of the present.

Perhaps that is why every attempt at continuation feels insufficient. Because, in the end, Chinatown was never a specific place. It was always the realization that understanding the world does not necessarily mean being able to change it.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu