Even before cinema learned how to speak, Germany in 1927 released a film bold enough to imagine the world of 2026. Reaching that year turns Metropolis into more than a classic: it becomes a reality test. Not because it got technological details right, but because it understood — far too early — how the future would organize itself socially, economically, and psychologically.

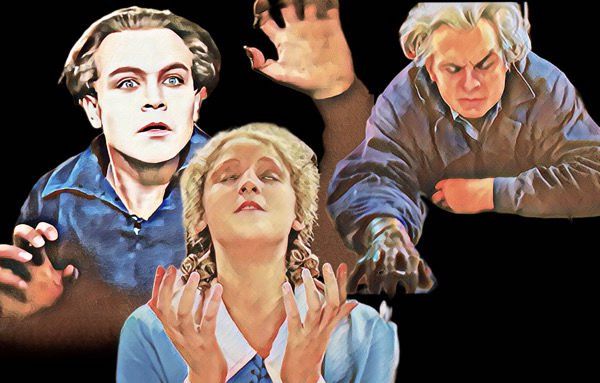

Directed by Fritz Lang and adapted from a novel by Thea Gabriele von Harbou, Metropolis is often cited as the first major cinematic representation of Artificial Intelligence. That label, while accurate, barely scratches the surface. The film doesn’t imagine machines; it imagines the political use of technology. And that is where, a hundred years later, the discomfort begins.

In fiction, Metropolis is a vertical city. At the top, the elite live surrounded by light, leisure, and hanging gardens. Underground, workers operate gigantic machines, repeating mechanical movements until exhaustion. In 2026 — the real one, not the fictional version — we don’t literally inhabit a single city, nor do we physically descend underground to work. But the division exists, and it may be even more efficient. Today’s “below” is social, economic, and digital. It isn’t easily visible, but it sustains everything.

The film imagined labor as an extension of the machine. In 2026, that proved true in a less literal and more brutal way. Workers are no longer crushed by colossal gears; they are absorbed by abstract systems. Algorithms determine productivity, visibility, relevance, and even permanence. Exhaustion is no longer merely physical; it is mental, continuous, with no off switch. On this point, Metropolis got the diagnosis right; it only missed the aesthetic.

Another unsettling accuracy lies in communication. The film shows Joh Fredersen controlling the city from an office filled with screens, buttons, and indicators, speaking to subordinates via video. In 1927, this was pure fantasy. In 2026, it is banal. Not only do we hold meetings by video; decisions affecting millions are made from digital panels, dashboards, and command centers that compress entire realities into data. Power, as Lang intuited, has become remote, technical, and deeply impersonal.

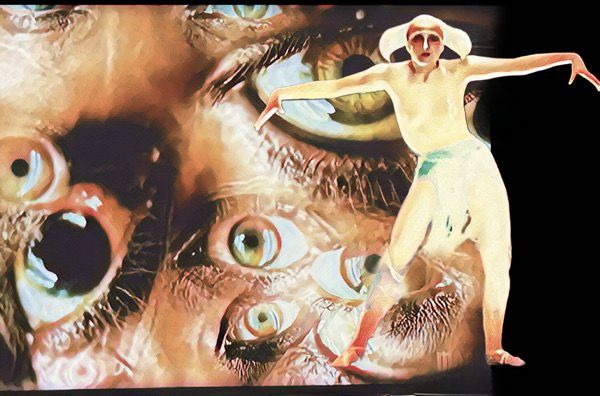

But the most disturbing comparison between fiction and reality lies in Artificial Intelligence itself. In Metropolis, the android HEL — the Maschinenmensch — is created to manipulate, confuse, and incite chaos. She does not rule by force, but by the appearance of legitimacy. She has a human face, seductive rhetoric, and the ability to mobilize emotion. In 2026, we don’t have humanoid robots leading revolutions, but we do have deepfakes, synthetic voices, avatars, and automated narratives capable of generating panic, devotion, or hatred at global scale. The method is the same. Only the interface has changed.

There is, however, an irony that only becomes fully visible in 2026. In Metropolis, the machine does not begin as a docile tool of power; it becomes a destabilizing element, something that threatens to set the system that created it on fire. Reality took a different path. Technology rarely escapes elite control; when it seems dangerous, it is quickly absorbed, regulated, and monetized. Lang feared loss of control. We fear efficiency.

The film “fails” when it suggests that conflict could be resolved through moral conciliation — the famous idea that “the mediator between the brain and the hands must be the heart.” In 2026, power is no longer concentrated in a visible figure who can be persuaded or humanized. It has dissolved into systems, platforms, invisible investors, and automated decisions. Conflict is no longer direct; it is diffuse, informational, and cultural. In this respect, reality proved more complex — and harder to confront — than the film imagined.

Metropolis also bet on a hyper-physical industrialization that never fully materialized. Monumental factories gave way to minimalist offices, remote work, and silent automation. But that error is superficial. What the film truly foresaw was the gradual removal of the human being as the system’s center — and that happened. Today, people don’t disappear beneath machines; they disappear beneath metrics.

Lang imagined a future in which technology would still require heavy, almost brutal manual labor. That didn’t come to pass literally, but the spirit remains. In 2026, automation promises liberation while reorganizing labor into ever more precarious layers. Artificial Intelligence doesn’t eliminate human effort; it displaces it, fragments it, and renders it less visible. The machine keeps turning — it has only changed shape.

Perhaps Metropolis’s greatest insight was understanding that technology is never neutral. It reflects the fears, the desire for control, and the obsessions of those who create it. HEL is not a villain because she is a machine, but because she mirrors an inventor driven by resentment and power. In 2026, we keep making the same mistake: we discuss Artificial Intelligence as if it existed in isolation from politics, economics, and human inequality. Lang and von Harbou already knew that was an illusion.

Reaching 2026 does not make Metropolis a “dated film that got a few things right.” It makes it a film that understood the future better than we would like. It didn’t predict gadgets. It predicted structures. It didn’t guess forms; it grasped logics. And that may be why it remains so current: the future it feared did not arrive with the roar of giant machines, but with clean interfaces, automated decisions, and a form of control so efficient it often feels invisible.

Watching the film today is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is a mirror. And like any good mirror, it doesn’t show technologies. It shows choices. And if there is one thing Metropolis truly failed to anticipate, it is the degree of resistance elites would show to any real rebalancing. The film bets that extreme confrontation could produce empathy, that proximity to collapse might awaken conscience. A century later, that may be its most naïve fantasy. Robots, vertical cities, and technological control seem plausible. The idea that economic inequality might be reduced without political conflict — through goodwill alone — sounds, today, even more distant than it did in 1927.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.