We enter the year of Marilyn Monroe’s centenary, and few symbolic dates feel so heavily charged. This is not merely about remembering a famous actress, but about confronting the greatest myth Hollywood ever produced and perhaps the most resilient one. Some stars age with their films, others with their images. Marilyn crosses generations without asking permission, awakening the same passions, projections, and disputes more than six decades after her death. The mystery that surrounds her does not diminish with time. It grows. And it says as much about us as it does about her.

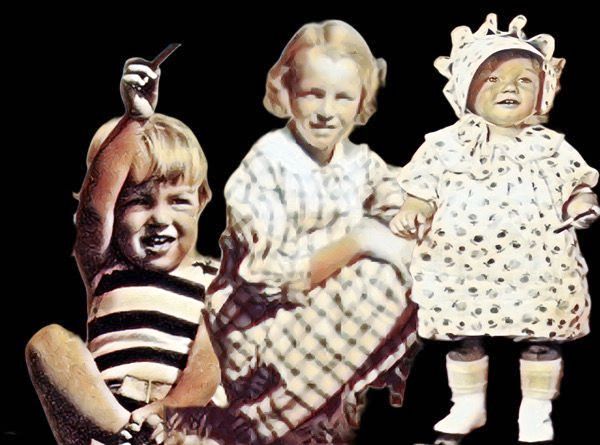

Norma Jeane: a childhood without ground

Marilyn was born Norma Jeane Mortenson on June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles. Her father’s name was never definitively recorded. Her birth certificate reads “unknown,” and that absence has been filled over the years with hypotheses that never fully close. The most frequently cited name is Charles Stanley Gifford, an RKO executive with whom her mother is believed to have had an affair. Others point to Edward Mortensen, her mother’s husband at the time, although chronology and later examinations make this version unlikely. Other names appeared in sensationalist books, always without conclusive proof. The inescapable fact is that Norma Jeane grew up without a father, knowing only that he existed somewhere and never chose to acknowledge her. This absence is not a biographical detail. It is a structural wound.

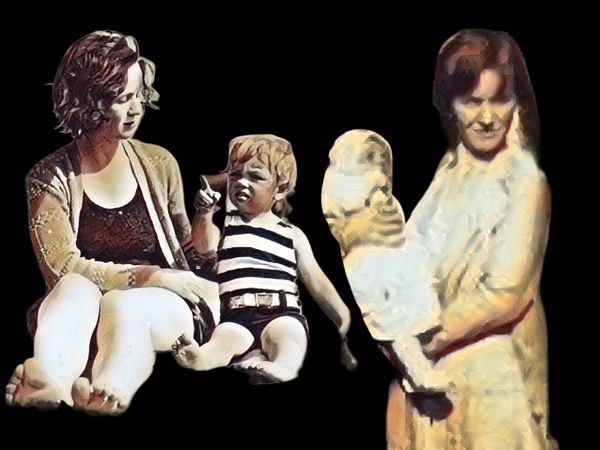

Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker, worked as a film cutter at RKO and suffered from severe psychiatric illness, today associated with paranoid schizophrenia. Gladys was institutionalized for the first time when Norma Jeane was still a child, spent long periods in psychiatric hospitals, and was never able to raise her daughter.

Norma Jeane was raised by foster families, spent time in an orphanage, and lived an unstable childhood marked by constant displacement, loneliness, and, later, reports of abuse. None of this aligns with the image Hollywood would later sell. And perhaps that is why the contradiction between the abandoned girl and the most desired woman in the world remains so difficult to reconcile.

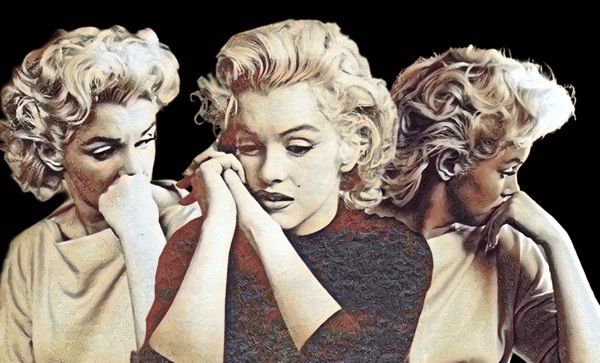

From Norma Jeane to Marilyn: the invention of a persona

The transformation of Norma Jeane into Marilyn Monroe was not merely a change of name. It was a conscious process of construction, refinement, and selective erasure. Under contract with Fox, she dyed her hair, modulated her voice, learned how to move before the camera, and, above all, understood what Hollywood wanted from her. Marilyn was born as a character carefully designed for the male gaze of the time, but also as a tool of social ascent for a young woman who knew that without that persona, she would return to invisibility.

That process had a central figure: Johnny Hyde. A powerful agent, lover, and mentor, Hyde believed in Marilyn’s potential when few took Norma Jeane seriously. He negotiated contracts, opened doors, taught strategy, and tried to shield her from the most obvious traps of the system. When Johnny Hyde died suddenly in 1950, at the age of 47, Marilyn lost not only a romantic partner but her primary anchor within the industry. Many biographers agree that had he lived longer, her trajectory might have been less erratic and less lonely.

Hollywood, desire, and control

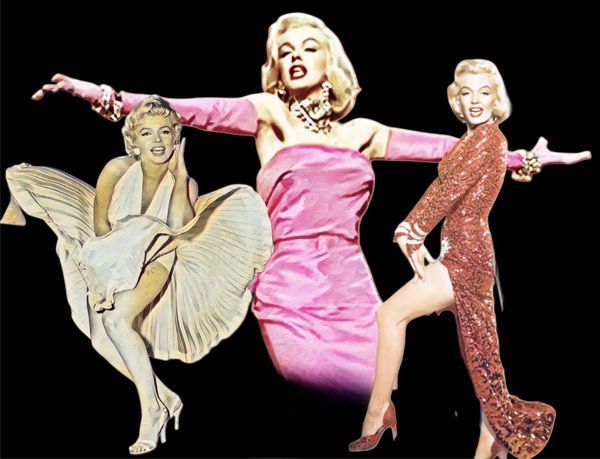

When Marilyn emerged as a star in the 1950s, she did not simply invent a new feminine type. She redefined desire on screen. Her curvaceous body, breathy voice, impeccable comic timing, and acute awareness of the effect she produced made her something rare: a sex symbol who understood her own mechanism.

Films such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, How to Marry a Millionaire, and The Seven Year Itch solidified the persona. But it was Some Like It Hot that revealed what she always knew, and few were willing to acknowledge: Marilyn was an extraordinary comedienne, with absolute command of rhythm, pause, gaze, and subtext. The laughter she provoked did not come from naïveté, but from intelligence.

That talent, however, was rarely respected on equal terms. Hollywood treated Marilyn as an extremely profitable but disposable product. Delays on set, emotional crises, and contractual conflicts were seen less as signs of illness and more as flaws in a difficult commodity.

Marilyn fought Fox for better roles, created her own production company, studied at the Actors Studio with Lee Strasberg, and sought recognition as a “serious” actress. She understood that her beauty opened doors but also closed them. She knew that public desire turned her into merchandise. And she knew that the industry preferred fantasy to the real woman. That tension runs through her entire adult life.

Love, shelter, and the repetition of abandonment

In her personal life, the same pattern repeats. Marilyn searched for protection, belonging, and validation. At sixteen, she married her neighbor James Dougherty, a choice driven less by romance than by survival: he could support her and offer a home at a moment when her foster parents no longer intended to keep her.

By then, Norma Jeane had passed through approximately eleven foster homes, in addition to a period in an orphanage during her childhood and adolescence. The exact number varies slightly among biographers, since not all placements were formally recorded, but this is the historical consensus. Instability was not an exception in her life. It was the rule. The marriage to Dougherty ended when Norma Jeane began working as a model, a discovery that would lead her toward her dream of becoming an actress and, at the same time, definitively close that first attempt at shelter.

Later, already as Marilyn Monroe, came the relationships the world followed with curiosity and, often, cruelty. There was the affair with Yves Montand during the filming of Let’s Make Love, a brief and ambiguous relationship that once again exposed Marilyn’s loneliness within a system that blended desire, power, and convenience. There was also the intense and unstable involvement with Frank Sinatra, perhaps her most enduring relationship outside marriage, marked by complicity, excess, and a mutual attempt at protection that never fully succeeded.

In the realm of the most controversial speculation, allegations of relationships with John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy persist to this day. Never definitively proven, these stories endure because they reinforce the image of Marilyn as a dangerous woman through proximity to power.

Within marriage, her trajectory followed the same movement. Joe DiMaggio loved her but could not tolerate the public exposure and tried to control it. Arthur Miller, her last husband, admired her intellectually but withdrew when her fragility became inconvenient, unable to reconcile the real woman with the symbol projected by the world.

Marilyn suffered miscarriages, endured profound depression, developed a dependence on prescribed medication, and experienced a growing sense of loneliness, even when surrounded by people. The image of the woman desired by everyone concealed someone who rarely felt truly chosen.

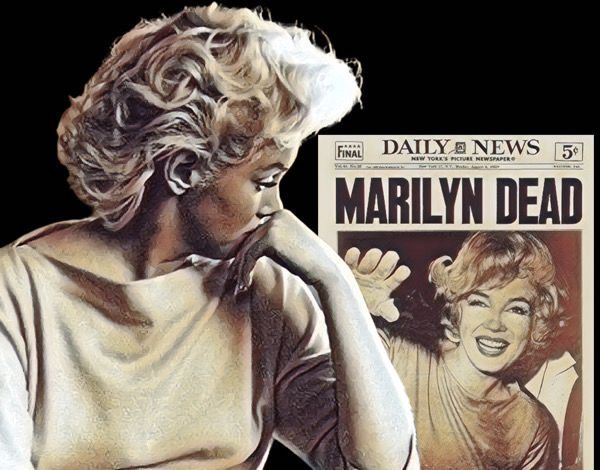

A suspicious death and the final paradox

Her death, on August 5, 1962, at the age of 36, sealed the myth. Marilyn was found naked in her home, alone, with a telephone beside her bed and pill bottles scattered around. The official cause was a barbiturate overdose, classified as probable suicide. Since then, theories have multiplied. Mafia involvement, government cover-ups, political silencing, and medical accidents. None has been proven. All survive because the official version feels too simple for a figure so burdened with symbolism and because there were real failures in the investigation, contradictions in testimonies, and an eagerness to close the case.

There is also a central paradox. At the moment of her death, Marilyn was experiencing a tangible professional decline. Her recent films were earning less, studios saw her as a liability, and her public image was beginning to erode. Her death, however, instantly reversed that process. The public fell back in love with her with renewed intensity. Failure became injustice. Instability became poetic fragility. A flawed woman became a legend. Death interrupted the wear and tear and froze Marilyn at an eternal point of desire and mystery.

Norma Jeane, Marilyn, and the impossibility of rest

The fascination persists because Marilyn embodies contradictions that still unsettle us. She was both a victim and a strategist. Naïve and calculating. Strong and fragile. A woman who consciously built a public image and was simultaneously crushed by it. We try to decode her because we want to resolve that paradox. We want to believe that by understanding Marilyn, we might understand something about fame, desire, misogyny, and loneliness in the modern world.

It is no coincidence that her life has been retold so many times. Blonde reduced Marilyn to suffering, erasing her intelligence and agency. My Week with Marilyn offered a more delicate and human perspective. Neither closes the enigma.

The question that remains, one hundred years later, is not only who killed Marilyn Monroe. It is why we still need that answer. Perhaps because accepting that she died alone, exhausted, and poorly cared for by a system that exploited her is more disturbing than imagining a conspiracy. Marilyn asked, in her last interview, not to be treated as a joke. She wanted respect as an artist. She wanted to be seen beyond her body.

Perhaps we will never fully know who Marilyn Monroe was. Perhaps we can only approach Norma Jeane, the girl who wanted to be loved, and the woman who wanted to be respected. As long as we insist on deciphering her, Marilyn remains with us. The challenge, one hundred years later, is learning to look at her with less appetite and more listening.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.