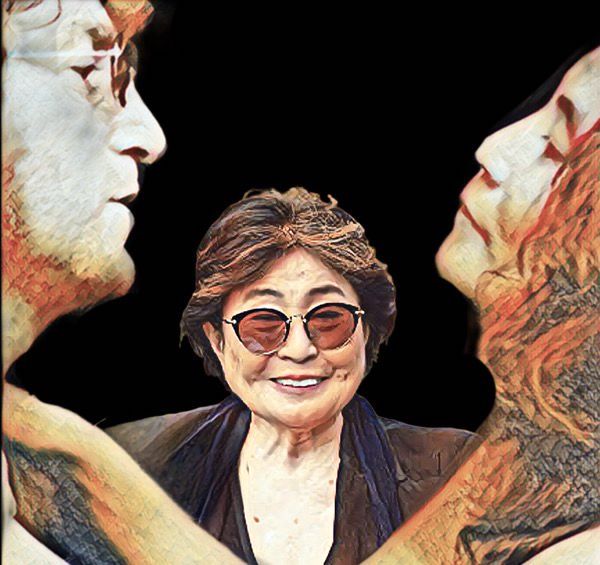

For decades, Yoko Ono’s story was told as an uncomfortable footnote in the biography of John Lennon. More recently, she has been revisited as a symbol of historical misogyny: a convenient scapegoat for the end of The Beatles. The two recent documentaries that orbit this period — One to One: John & Yoko and Daytime Revolution — are not satisfied with either version. They do something rarer: they restore complexity to a relationship that was always treated in overly binary terms.

One to One: John & Yoko, directed by Kevin Macdonald, arrived in theaters in IMAX format for a reason (later on HBO Max Platform). At its center is the benefit concert held at Madison Square Garden in August 1972, featuring Lennon, Yoko Ono, and the band Elephant’s Memory. It was the only full concert Lennon performed after the Beatles’ breakup and before his death. But to describe the film as merely a concert movie is to miss its core intention. The performance serves as a gateway. From it, the documentary pulls us into the political, emotional, and domestic life of the couple in the early 1970s, when New York became the gravitational center of their existence.

There is an important aesthetic choice here: there are no talking heads explaining what we should think. The film is built almost entirely from archival material: images, recorded phone calls, news footage, and intimate domestic moments. The sensation is immersive, as if we were dropped into 1972, seeing the world through John and Yoko’s eyes. Sean Ono Lennon, who worked directly on the new audio mixes for the concert and followed the project closely, articulates with unsettling precision what the film reveals about his parents: they functioned as the first celebrity couple to live in a permanent state of exposure, long before reality television, social media, or the idea of intimacy as content.

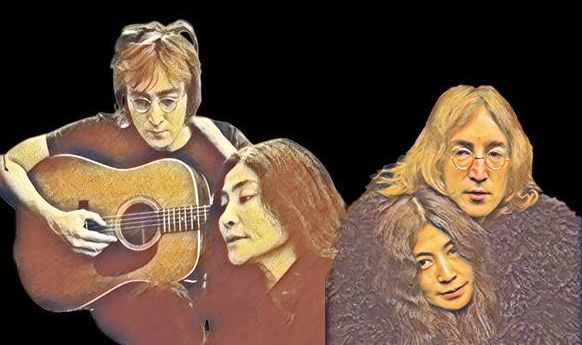

That perception changes everything. Lennon and Ono did not simply love each other; they documented their love as a political act. They recorded phone calls because the FBI was monitoring them. They filmed their daily lives because they wanted control over their own narrative. Slogans like “Give peace a chance” or “War is over if you want it” were not just phrases; they were early memetic campaigns, before we had the language for that. By showing themselves raw and unpolished, they anticipated a logic of performative transparency that today feels commonplace but in the early 1970s was radical.

This is where Daytime Revolution functions as an almost perfect companion piece. The documentary follows the week in 1972 when John and Yoko co-hosted The Mike Douglas Show, then the most-watched daytime program on American television, with an audience of roughly 40 million viewers per week. This was not an alternative or countercultural space. It was the living room of Middle America. And yet, they turned that platform into a political arena. They spoke about police brutality, feminism, racism, and environmental issues. They invited figures such as Ralph Nader, Bobby Seale, and George Carlin. It was a calculated gesture — and at the same time, dangerously naïve — to use the machinery of mainstream television to confront the very comfort it was designed to sell.

Seen together, the two films help explain why millennials and younger generations respond so differently to Yoko Ono. They did not grow up under the dogma that she “broke up the Beatles.” They grew up accustomed to fused couples, shared identities, and public lives with no clear boundary between the personal and the political. When they look at Yoko, they see an artist shaped by war trauma, displacement, and loss. They see a woman whose work always demanded discomfort from the audience. And above all, they see someone who never tried to be palatable.

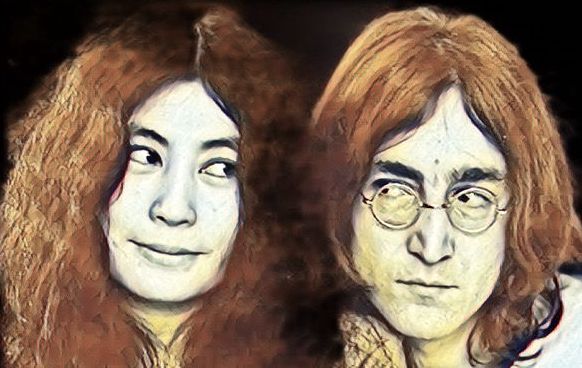

I followed this same path of reassessment. For years, I absorbed the inherited narrative: Yoko as intruder, as noise, as obstacle. Over time — and through the band’s own testimonies, especially in The Beatles Anthology — it became impossible to sustain such a simplified version. The Beatles’ exhaustion was deep, structural, and openly acknowledged by the four of them. Artistic divergence, power struggles, emotional fatigue. The end would have come regardless.

Still, there is a delicate point that neither documentary erases — nor should they. Lennon and Ono’s relationship was marked by extreme codependency. They did not merely love each other; they fused into a single entity, inseparable both physically and symbolically. Yoko was always present because Lennon needed her to be. Within a group sustained by fragile balances, that fusion was explosive. Not because Yoko sought to destroy anything, but because Lennon could no longer — or no longer wished to — inhabit two worlds at once.

This fusion is where the historical accusation is born. Not as factual truth, but as an emotional reaction. From the outside, it was easier to blame Yoko’s visible presence than to confront Lennon’s gradual absence as a Beatle. Their codependency does not negate empathy for Yoko; it complicates it. It allows us to understand how love, trauma, and activism are intertwined to the point that any return to the past has become impossible.

One to One: John & Yoko may be the film that comes closest to doing justice to this complexity. Sean Lennon has said he has never seen such an honest portrayal of his mother. That matters. This is not sanctification; it is listening. Yoko speaks for herself, in context, without caricature. Her pain, intelligence, artistic rigor, and contradictions emerge without condescension.

In the end, what these documentaries expose is not only the mystery of Yoko Ono, but our persistent need for simple narratives to explain emotionally difficult endings. Blaming Yoko was always more comfortable than accepting that the Beatles ended because they grew, changed, and chose incompatible paths. Revisiting Yoko today does not erase the tension she represented. It recognizes that she was never the sole cause, and that she may have been, from the beginning, the most uncomfortable mirror of an inevitable ending.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.