As published in Revista Bravo!

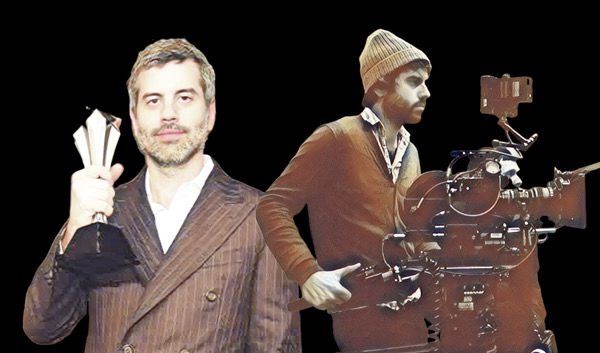

Not everyone sits down to watch a film, paying attention to the cinematographer’s name or remembering their contribution to the final result. But almost every viewer recognizes when they are facing images that feel like paintings, because they move us by what they convey and, above all, by what they evoke in us. For us, Brazilians, this year’s international awards season is yet another sign of the strength of artists working behind the camera who continue to stand out year after year. The 2026 Critics’ Choice Awards honored Adolpho Veloso for Train Dreams, a recognition that is unlikely to be the last as the race heads toward the Oscars.

In the case of Train Dreams, this is not simply about “beautiful” or technically accomplished cinematography. What Veloso builds in Clint Bentley’s film is an emotional grammar. The image does not illustrate the story; it writes it. Every landscape, every shift of light, every visual silence actively participates in the narrative. Train Dreams would not be the same film without the sensitivity of the Brazilian cinematographer who conceived it as a memory rather than a record.

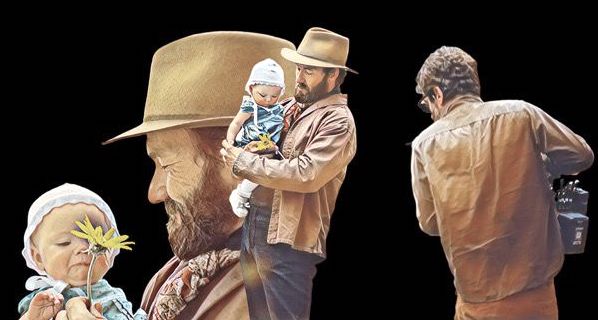

Veloso comes from a place that explains much of his cinema. Brazilian, now based in Portugal and working primarily in the United States, he carries in his own path the experience of displacement. He is a foreigner in almost every territory he inhabits. And it is precisely this condition that shapes his gaze: attentive, respectful, always willing to observe before imposing form. In Train Dreams, the story of Robert Grainier, the itinerant worker played by Joel Edgerton, finds a direct echo in this biography. This is a man who spends months away from home, building railroads, cutting down trees, moving through lands that never fully belong to him. In filming a life defined by departures and uncertain returns, Veloso does not look from the outside. He recognizes.

That gaze, however, is not accidental. Adolpho Veloso discovered cinema very early, when films became, for him, a way of crossing worlds. He did not come to cinematography through photography as a formal discipline. He became a cinematographer because he loved stories and wanted to tell them through images. This distinction is essential to understanding his work: Veloso does not treat the camera as an instrument of virtuosity, but as an emotional language. As he began his training in the audiovisual field and worked in independent productions in Brazil, he built a relationship with the image based less on effect and more on experience.

There is a turning point he often mentions. Watching City of God, shot by César Charlone, he realized that one did not need to belong to hegemonic centers to create images capable of speaking to the world. It was possible to make powerful cinema “from here.” That awareness runs through his entire trajectory. Before reaching high-profile international productions, Veloso developed his signature in projects that already revealed an affinity with nature, with real light, and with characters in transit. A decisive example is Rodantes, by Leandro Lara, filmed in the Amazon region of Rondônia, where the transforming landscape already emerged as a narrative force. The relationship between territory, body, and memory that would later define Train Dreams was already there, in embryonic form.

His name began to circulate beyond Brazil when he shot the documentary On Yoga: The Architecture of Peace, directed by Heitor Dhalia. That film caught the attention of Clint Bentley, who invited him to shoot Jockey in 2021. More than a one-off collaboration, a deep aesthetic and human partnership was born. In Jockey, Veloso consolidated a method marked by small crews, extensive use of natural light, a camera close to the actors, and a radical openness to chance. That creative laboratory is the foundation of Train Dreams.

Since then, his international career has expanded without abandoning this authorial ethic. Veloso shot the series Becoming Elizabeth—one of my favorites of 2022, whose work with natural light is striking even in a production from a platform considered “smaller” in the global circuit—and features such as Queen at Sea, by Lance Hammer, as well as Remain, by M. Night Shyamalan, starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Phoebe Dynevor. Along the way, he has accumulated technical recognition from festivals and professional associations, with nominations from organizations such as the ASC and Camerimage. Still, he resists the idea of a fixed “style.” Each project, he insists, demands a new kind of listening.

It is with this background that he arrived at Train Dreams. Not as a technician hired to “beautify” a period drama, but as a co-author of the narrative experience. Veloso and Bentley conceived the film as if the viewer were leafing through a box of old photographs, out of order, trying to reconstruct a life from fragments. The image is not organized as objective chronology but as memory—sometimes luminous, sometimes hazy, always subjective. Hence, the choice of the 3:2 aspect ratio was inspired by photography and the decision to shoot as if the camera were visiting memories rather than reconstructing the past.

Nothing encapsulates this ethic of looking better than the fact that has become emblematic: Train Dreams was shot using 99% natural light. Not as a technical fetish, but as a conviction. For Veloso, the world’s light is dramatic material. If it rains when the sun is expected, he films the rain. If the sky changes, the scene changes with it. Nature is not a backdrop; it is a character. Forests, rivers, snow, fire, and above all, the wildfire that devastates the landscape and alters the protagonist’s destiny act as narrative forces. When green gives way to ash, it is not a stylized effect. It is reality imposing itself on the image. The cinematography does not beautify destruction; it recognizes it as trauma.

The same rigor permeates moments of intimacy. The scenes in the cabin where Robert lives with Gladys, played by Felicity Jones, often emerged from improvisation. Veloso simply followed the actors with the camera, allowing them to interact with the space, with animals, with the baby, with the river. There were no rigid marks, no choreography imposed by technique. The image adapted to the gesture, not the other way around. That is why these apparently small moments carry such emotional density. The film makes us feel the everyday, not merely observe it.

When one speaks of “award-worthy cinematography,” the tendency is to think of technical virtuosity. Veloso’s work moves in the opposite direction. He does not stand out for spectacular camera moves or for an aesthetic that calls attention to itself. His strength lies in translating emotion into image. When portraying the happiest period of Robert’s life, for instance, Veloso chose a warm light, often captured at dusk. Not because that time was literally more golden, but because that is how memory works: we remember our happiest moments with a glow that may never have existed as we now reconstruct it. Cinema here does not reproduce reality. It translates the experience of remembering.

The final scene condenses this philosophy. When Robert enters an airplane for the first time and, from above, sees his life pass through his mind in fragments, the film organizes itself as a flow of memories. When he saw the finished sequence for the first time, with Nick Cave’s music emerging over the credits, Veloso was moved. Not out of vanity, but because he recognized there the synthesis of what he sought: a cinema that does not explain emotions, but allows them to exist.

The place Adolpho Veloso occupies today did not come out of nowhere. He dialogues with a tradition of Brazilian cinematographers who have achieved international recognition and major awards. Adriano Goldman is perhaps the best-known example, an Emmy winner for The Crown and the visual architect behind series such as Narcos. In cinema, names like Lula Carvalho, awarded at Cannes in 1962 for The Given Word, and Affonso Beato, Oscar-nominated for Dick Tracy, opened paths when Brazilian presence behind the camera in Hollywood was still the exception. More recently, Daniela Shaw has been building a solid career on major series, while other Brazilian professionals work consistently on global productions, even if the freelance nature of the profession makes any precise count impossible.

Veloso joins this lineage with a signature of his own. His references range from Roger Deakins and Sven Nykvist to Andrei Tarkovsky, but he often points to Gordon Willis as a decisive influence for the courage to sustain an authorial vision even under industrial pressure. This fidelity to a personal vision is also reflected in another recurring trait of his discourse: the need to return to the point of origin.

Whenever he can, Veloso returns to Brazil to see people “who look like you, who speak like you, doing what you want to do.” In an awards season marked by noisy disputes and aesthetics of grandeur, Adolpho Veloso’s work has been quietly earning its rightful prominence. More than a likely recipient of further trophies, he emerges as one of the figures who best embody what cinema can be when image and emotion move together: a space of memory, humanity, and beauty without artifice.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.