You can judge me and find it odd, but it was precisely the delay and the lack of appeal that horror films usually spark in me that made me take so long to watch it. Still, I found Weapons an absolutely incredible film. Here, the effect of the genre’s classic formulas is different. Zach Cregger builds a kind of horror that is not born from shock, but from unease, something that infiltrates little by little until it disrupts our perception of the world. The film begins as a mystery, slips into communal paranoia, and, when you think you have understood the rules of the game, it shifts gears. Not to be “clever,” but to be more cruel: Weapons wants the viewer to feel the fragmentation before understanding it.

The premise is simple and devastating. In an apparently ordinary town, 17 children from the same classroom disappear on the same night, at the same hour, leaving behind only one student: Alex. The impact is immediate, but the film refuses to follow the comfortable path of a linear “case.” Instead, Cregger opts for a narrative built from perspectives that alternate and collide. This device, so abusively used by films that confuse puzzle-making with depth, is not ornamented here, and it makes sense. The story breaks because the town breaks; grief breaks because there is no single culprit; logic breaks because trauma does not organize itself in a straight line. Form is content.

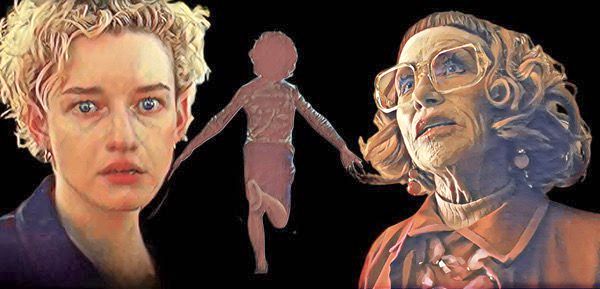

There is something particularly unsettling in the decision to narrate part of the events through an unidentified child’s voice, a point of view with no face, no defined body, hovering over the plot as witness and threat at the same time. It is not a reliable narrator, nor an empathy device. It is displacement. Suddenly, we do not know exactly who is speaking, but we feel that something is watching us. This is the kind of dread that does not depend on seeing, but on imagining, and it was impossible not to think of films that understood, long before us, that the most effective horror is the kind that does not respect the boundary between “it happened” and “it could happen.” Rosemary’s Baby. And, above all, The Blair Witch Project. Not because of aesthetic similarity, but because of the same sensation that the horror is not in the image; it is in what the image forces us to complete.

A “simple” plot to amplify fear

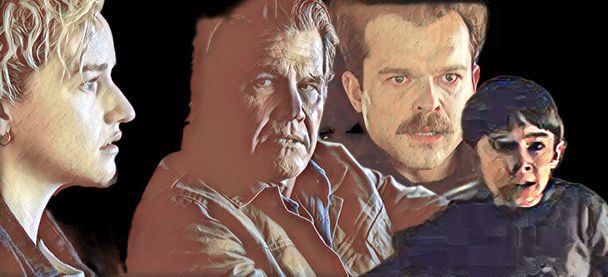

The film follows the aftermath of the simultaneous disappearance of the 17 children and the reaction of a community trying to make sense of the impossible. Security-camera footage shows the students leaving their homes in the middle of the night, alone, moving with a strange determination, almost as if they were being drawn by an invisible force. The class teacher, Justine Gandy, becomes the predictable target of some parents’ confusion and rage; she insists on her innocence while the town looks for culprits that might soothe its pain. Alex, the only student who did not vanish, comes to occupy an ambiguous position: witness, survivor, and, in some people’s eyes, the piece that does not fit. The formal investigation advances erratically, while the film alternates points of view — domestic, institutional, and intimate — as if each chapter were an attempt to organize chaos. When a figure who had been peripheral until then, Aunt Gladys, enters the story, the mystery shifts: what seemed like a communal collapse begins to reveal a mechanism of control that instrumentalizes people, especially children, for atrocious ends. The third act lays out this method and shows how Alex, by understanding its logic, manages to reverse it. The narrative does not close with total explanations: what remains is an apparent return to normalcy and the feeling that something essential went unnamed. A classic open road toward the already confirmed prequel and a possible continuation.

None of this is accidental. Cregger conceived Weapons as a film about social collapse told through shards. He starts from an event that is impossible to assimilate and observes what happens when each character tries to make sense of the unbearable through their own guilt, fear, or despair. The filmmaker has cited the interwoven structure of Magnolia as an emotional reference for following multiple stories in parallel, and the atmosphere of Prisoners as a model for that damp, gray unease in which the threat seems to soak into the space. There is also a declared shadow of Stephen King: a small town, children in danger, a mystery that feels supernatural, but always carries a moral subtext. Not by chance, the film plays with signs and codes that feel like nods to that universe — and, for cinephiles, this deepens into a direct connection with Stanley Kubrick and The Shining. The insistence on numbers and precise times, the construction of corridors and spaces as mental labyrinths, the use of emptiness as a dramatic element, and even the idea of an evil that lodges itself in ordinary places and ordinary people echo the way Kubrick turned horror into a sensory and psychological experience. There is an aesthetic and conceptual lineage here that is not fetishism: it is method. For those who recognize this grammar, Weapons gains an extra layer of sophistication.

Cregger also masters a classic principle of suspense: suggest the worst and delay the reveal. He builds expectation the way you tighten a cord, using time and editing to keep us on alert. In one of the most disconcerting sequences, perversity is not in what moves, but in what stays still: two people sitting, absolutely motionless, and it is precisely that stillness that becomes unbearable, as if the absence of action were the cruelest form of violence. Horror here is born less from gesture and more from the refusal of gesture.

There is also a moment of extracinematic shock that Cregger handles with precision: the appearance of a semiautomatic rifle, an object that carries an unavoidable symbolic weight in the United States. In a film that begins with the disappearance of children, the image summons, even if the screenplay never names it directly, the real-life tragedies that haunt American schools. A Hora do Mal does not turn into a manifesto, but it uses that sign to unsettle us, reminding us that the terror we see on screen converses, however obliquely, with the world beyond it.

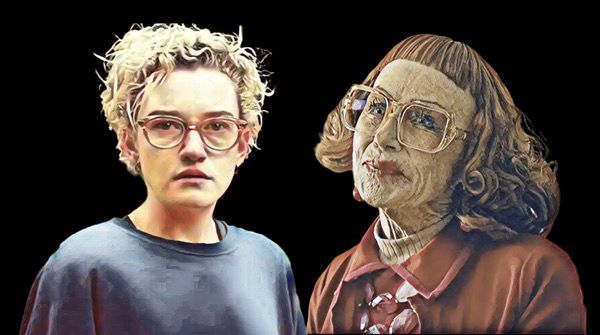

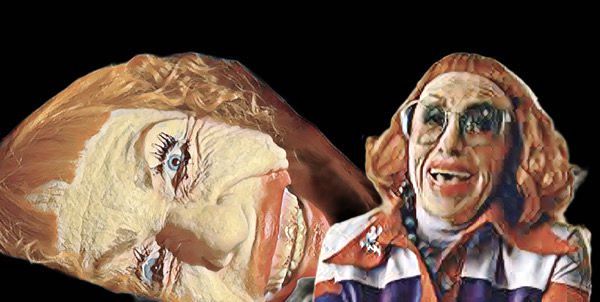

Until nearly an hour in, the film finds its axis. Amy Madigan enters the scene. And nothing stays in place. She plays Aunt Gladys, a presence that seems to have always existed in that family, on that street, in that collective memory. Eccentricity, cruelty, and charisma in equally disconcerting proportions. Madigan does not “do” a villain; she embodies a logic. Her Gladys is not histrionic, does not seek shock, and does not need explanations. She occupies space with unsettling naturalness, as if evil were simply an alternative way of being in the world.

Visually and conceptually, Gladys evokes a very specific kind of horror. There is something of Minnie Castevet, from Rosemary’s Baby, in her: the figure who infiltrates everyday life under the mask of familiarity, the “aunt,” the neighbor, the long-standing presence no one questions. At the same time, she is the very incarnation of the Blair Witch, not as a creature of the forest, but as a force with no clear origin, operating through manipulation, ritual, and the use of others for atrocious ends. Gladys does not merely attack; she instrumentalizes. She uses children. She uses victims. She uses relationships. And she does it with a calm that destabilizes because it does not ask for forgiveness.

A modern update of The Pied Piper of Hamelin

It is impossible not to read Weapons as a dark update of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” the folk tale recorded by the Brothers Grimm. In the fable, a stranger rids the town of rats with his music; when the townspeople refuse to pay what was agreed, he returns and, in revenge, leads the children out of the town, never to return. The story has always been about collective punishment, a broken moral contract, and the price adults pay when they fail. Cregger transforms that structure into contemporary horror: Gladys does not play a flute, but seduces, guides, and instrumentalizes; she does not take the children away by enchantment, but by manipulation; she does not act as a distant myth, but as a domestic presence. The result is more disturbing than the original allegory, because it shifts the threat from the fantastic to the intimate. The “piper” now lives inside the home.

Echoes of Get Out: the horror of appropriation and weaponizing the other

There is also an inevitable contemporary association: Weapons dialogues with Get Out (by Jordan Peele), not because of plot similarity, but because of an affinity of logic. As in Peele’s film, the horror here is born from what seems safe, cordial, domestic and reveals itself as a system of appropriating the other. In Get Out, bodies are colonized; in Weapons, people are weaponized. In both, violence is not explosive by nature: it is methodical, smiling, bureaucratic in its efficiency. The fear does not come from a monster that invades, but from a structure that becomes normalized. This connection reinforces the contemporary dimension of Cregger’s film: its horror is not only atmospheric, but it is also moral and social, a commentary on how relationships, institutions, and affections can be transformed into tools of domination.

It is at this point that the title reveals itself. Weapons is not about weapons only in the literal sense; it is about weaponization. Gladys turns people into instruments. She converts bodies into tools, affection into mechanisms, trust into access. The method is as simple as it is disturbing: through an intimate link — a strand of hair, a physical fragment — she establishes control. A branch, a banal object, becomes the conduit of that domination. The horror is not in spectacle, but in the grotesque materiality of the process. Nothing is too intangible to be touched. Nothing is too human to be used.

From there, the film reorganizes itself. Everything that came before feels like a slow preparation for this collision. And this is where Weapons stops being merely a great horror film and becomes an emotionally destabilizing experience. Because what is at stake is no longer “what happened to the children,” but what we do when we realize that evil can wear the costume of familiarity. The town, which had been searching for external culprits, becomes the battlefield itself. Parents, teachers, authorities, neighbors: everyone short-circuits. Panic is not a side effect; it is part of the mechanism.

What works, and what requires our complicity

What works in Weapons is the coherence between form and theme: fragmentation is not a trick, it is a mirror; ambiguity is not evasion, it is an ethical position; the refusal to over-explain is not negligence, it is a strategy to make fear endure. At the same time, there are moments when the film depends on our willingness to overlook details to fully enter Cregger’s imagination. Not all points of view are equally engaging, and the segmentation itself, with overlapping chapters, sometimes feels more like a delay than a revelation. There are scenes of violence that flirt with excessive sadism and some genre clichés that creak. This tension — between aesthetic rigor and emotional buy-in — does not weaken the film; it defines it. Weapons does not want to be a logical manual. It wants to be an experience.

The flaw that is also criticized: the police

The main flaw — and, at the same time, an implicit critique within the film itself — lies in the performance of the local police. Institutional unpreparedness is embodied by Paul: an officer who reacts more than he acts, who pursues obvious leads while the essential slips away, who confuses control with understanding. Instead of providing containment, the police amplify disorder. The film seems to suggest that, when faced with the incomprehensible, the structures that should organize chaos often end up reproducing it. This is not merely dramatic inefficiency; it is social commentary. The investigation fails not because procedures are lacking, but because moral imagination is lacking, the ability to see beyond what fits into protocols.

The third act delivers twists that aim not merely to surprise, but to close a system. Alex, the only student who did not disappear, does not defeat Gladys through heroism in the classic sense. He confronts her through understanding. When he realizes that her power depends on that physical link, he reverses it: he uses a fragment of her, ties it to the instrument of domination, and breaks it. It is a solution almost brutal in its simplicity, and that is precisely why it works. The film had been showing us the rule all along; we were simply too absorbed by the noise of terror to see it.

The next sequence is one of the strongest images in recent horror cinema: the children, once captured, become the force that hunts her. Gladys runs, but the town seems reprogrammed against her; doors, windows, and corridors stop being obstacles. It is cathartic and repulsive at the same time. And, in a film that is about weaponization, it is coherent that punishment should come from the very instrument she chose.

But Weapons does not end as justice. It ends in unease. There is an appearance of normality in the ending, a gesture of “starting over” that could be read as closure. But the sensation is not relief; it is displacement. Because Gladys’s origin remains opaque. A witch? An entity? Trauma incarnate? The film refuses to stamp an answer. And that is exactly where it becomes more adult than most contemporary horror: by not over-explaining, it does not diminish fear; it extends it. If evil can disguise itself so convincingly as kinship, care, routine, what does it mean to “return to normal”?

That formal and thematic rigor also echoed beyond the screen. Weapons was not only a critical success; it was a box-office phenomenon, with impressive numbers for an original horror film. And, perhaps even more revealing, it crossed a barrier the genre rarely crosses: awards season. Amy Madigan’s Critics’ Choice win for Gladys did not feel like a concession; it felt like recognition of a performance that redefines what we understand as villainy in horror.

The conversation naturally moves toward the Academy. In a year when several award bodies have shown themselves more open to genre cinema, Madigan’s name starts circulating as a real Oscar possibility, not as a curiosity, but as a legitimate contender. Whether the nomination comes or not, the fact that Weapons is even part of that debate already says a great deal about the cultural weight the film has achieved. And it is worth remembering that Ruth Gordon won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for Rosemary’s Baby in 1968. My hope and my bet are on Amy Madigan.

What makes Weapons so special is that, in a genre often trapped by its own conventions, Zach Cregger’s film emerges as a work that understands horror not as effect, but as language: one capable of speaking about guilt, power, childhood, manipulation, and collective fear without ever losing aesthetic rigor.

When I left the theater, I did not feel as though I had watched “just another great horror film.” I felt as though I had seen a film that knows exactly what it is doing to the viewer, and that does not apologize for it. A Hora do Mal does not want comfort. It wants discomfort. It wants you to go home with the impression that something is out of place. And perhaps that is precisely why it already asserts itself, without fanfare, as one of the best horror films of today.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.