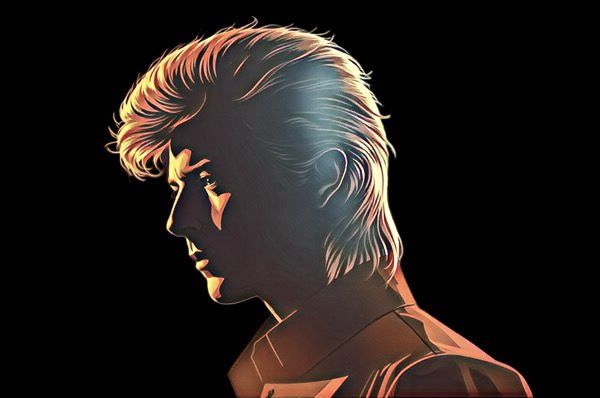

There are deaths that close trajectories. And some deaths open new readings. Ten years without David Bowie does not feel like absence, but like an active form of permanence. As if time, instead of distancing him, had done exactly the opposite: organized his work, confirmed his choices, and revealed the true scope of an artist who never wanted to be immediately understood.

When he died on January 10, 2016, two days after turning 69, Bowie left the world with the strange sensation that we had witnessed a final gesture that was already thought through, rehearsed, and choreographed. It was not merely the coincidence between the release of Blackstar and his death. It was the brutal awareness that he had transformed the end into language.

To understand why that final gesture never felt artificial, one must return to the origin, not as a founding myth, but as a construction. Bowie was born David Robert Jones on January 8, 1947, in Brixton, London, and grew up in an environment where music, theater, and image were never separate.

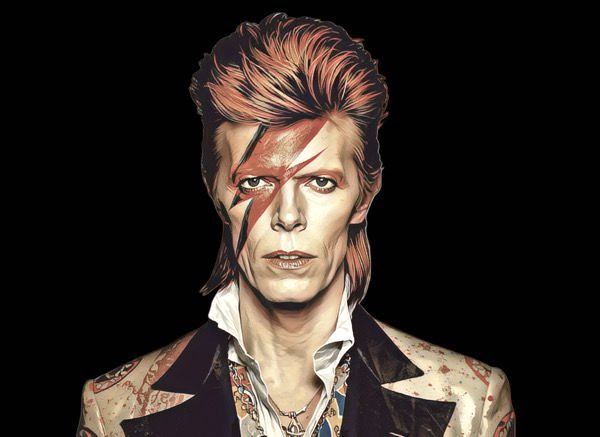

As a teenager, he studied art, graphic design, and theater at Bromley Technical High School, where he learned that creating is not simply expressing feelings, but shaping forms, signs, and personas. It was there that he grew close to George Underwood, a lifelong friend and future visual collaborator, responsible for decisive album covers such as Hunky Dory and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. In 1966, he chose to abandon the common surname “Jones” to avoid confusion with Davy Jones of the Monkees, and adopted the name “Bowie,” inspired by the Bowie knife—not as a fetish for violence, but as a symbol of rupture, of cutting away, of identity in constant reinvention.

In that period, Bowie was shaped less as a “singer” than as a total artist. He became a disciple of choreographer and mime Lindsay Kemp, who taught him to think of the body as narrative, performance as dramaturgy, and image as discourse. He moved through a London scene where music, fashion, and visual arts contaminated one another, the same environment that would give rise to art rock and glam through figures like Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music.

Musically, he absorbed everything: Little Richard, Elvis, Jacques Brel, Brecht, German Expressionism, American soul, European electronic music. And in parallel, he painted. His work in the visual arts was largely figurative and expressionist: portraits, studies of the human body, veiled self-portraits, dense colors, nervous brushstrokes, and a fascination with the face as a symbolic construction. He did not seek realism; he sought identity in a state of performance. For Bowie, music, theater, and painting were never separate fields. They were different languages for investigating the same obsession: who are we when we transform ourselves?

That formation explains why his body of work always functioned as a system in constant mutation. Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, Halloween Jack: characters that did not conceal David Jones, but examined him. Each persona was an experiment in identity, fame, desire, gender, power, and fragility. Bowie understood early what the world would only begin to discuss decades later: identity is not essence, it is construction. It does not reveal itself; it is performed.

Perhaps that is why he aged better than almost all of his contemporaries. Because he never sold the illusion of eternal youth. He chose transformation instead. When rock music crystallized myths, Bowie dismantled them. When the industry demanded repetition, he responded with displacement. From glam to soul, from the Berlin trilogy to the pop art of the 1980s, from the experiments of the 1990s to the strategic silence of the 2000s, nothing in his trajectory was gratuitous. Even the moments once deemed “minor” now read as chapters of a larger idea: art as process, not as a final product.

Blackstar remains, ten years later, one of the most radical gestures ever made by a popular artist in the face of his own finitude. There is no easy sentimentality there. There is strangeness, noise, and images that resist explanation. The video for “Lazarus” does not ask for empathy; it demands interpretation. Bowie does not cast himself as a victim or martyr. He places himself as the author to the very end. Controlling the narrative, not out of vanity, but out of aesthetic coherence. If his entire life was a work, the end could not be anything else.

That rigor also runs through Lazarus, the musical that premiered shortly before his death. It is not a disguised autobiography, but a thematic continuation of The Man Who Fell to Earth, a story already steeped in alienation, exile, and inadequacy. Bowie always felt like a foreigner: in his body, in his country, in his time. The stage was where that displacement became a creative force.

Ten years later, Bowie continues to be cited, revisited, reread, yet never exhausted. His influence is visible in music, fashion, cinema, pop culture, and above all in the idea that an artist does not need transparency to be honest. Bowie taught that mystery, too, can be a form of truth.

Perhaps that is why his presence remains so strong in 2026. In a world obsessed with exposure, Bowie built a career on the careful curation of what to show and what to conceal. In an era of rigid identities, he made fluidity a method. In a time that demands immediate answers, Bowie always worked through questions.

Ten years without David Bowie is not a prolonged mourning. They are in an ongoing dialogue. He did not remain in the past. And perhaps that is the greatest proof of his stature: Bowie did not die as a myth. He died remaining an artist, and true artists do not end when the body is gone.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu