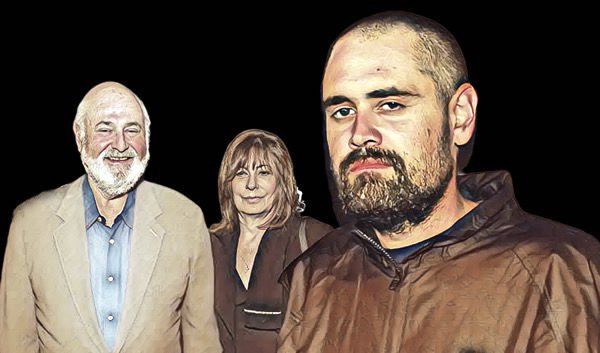

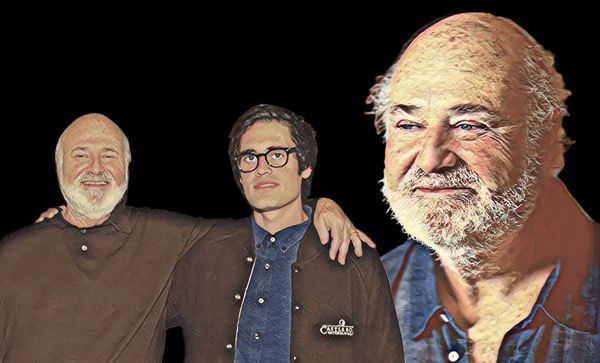

The case of Nick Reiner, suspect of the brutal killing of his parents, Rob and Michele Reiner, inside their own home in Brentwood, seems to move further away from any simple narrative about guilt, intent, and responsibility.

This week, when Nick was finally expected to enter his formal plea, the proceeding was once again postponed. Just before the hearing, his attorney, Alan Jackson — one of California’s most prominent criminal defense lawyers — officially asked to withdraw from the case. Without spectacle, without public explanation beyond a brief “we have no choice but to withdraw.” The judge granted the request. From now on, Nick will be represented by a public defender, Kimberly Greene. A new arraignment date has been set for February 23. Until then, he remains in custody, without bail, at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility.

Jackson’s departure, more than a procedural detail, adds an unsettling layer to a case that was already marked by ambiguity. This is not merely a change in legal strategy. In a case where everything seems to orbit the defendant’s mental state, the exit of a high-profile attorney on the eve of a hearing signals that even more delicate issues — clinical, ethical, evidentiary — may be unfolding away from public view.

From the beginning, the gravitational center of this story has not been only the crime itself, but the mind of the man accused of committing it. Nick, now 32, had a known history of substance abuse and, according to information that emerged in recent weeks, had been diagnosed with schizophrenia before the killings. Sources close to the case have said the medication he was taking made him “erratic and dangerous.” Even so, prosecutors have yet to present a clear motive for the murders or to detail how they intend to demonstrate premeditation — a key element in sustaining charges of first-degree murder with special circumstances.

On December 14, Rob, 78, and Michele, 70, were found dead in the master bedroom of their home, victims of multiple sharp-force injuries. Authorities have said there was an argument between father and son the night before, during a family gathering. Shortly thereafter, Nick was arrested and formally charged with two counts of first-degree murder with a special circumstance of multiple victims — a crime that in California can carry life imprisonment without the possibility of parole or even the death penalty.

But what has been unfolding since then is not a typical prosecution. At his first court appearance, Nick appeared disheveled, shackled at both hands and feet, wearing an anti-suicide smock. He spoke only three words: “Yes, your honor,” to confirm that he was waiving his right to a speedy arraignment. In that moment, the silence seemed to speak louder than any articulated defense.

Outside the courthouse, still acting as his attorney at the time, Alan Jackson delivered a statement that now reads almost like a premonition. He spoke of a “devastating tragedy,” of “very complex and serious issues” that would need to be examined carefully, without haste or rush to judgment. He asked for restraint, dignity, and respect for both the legal process and the family. A short time later, he would step away from the case.

Meanwhile, Nick’s siblings, Jake and Romy Reiner, addressed the public only to speak about the loss of their parents — “our best friends,” as they described them — and to ask that their grief not be turned into spectacle. No mention of their brother. No attempt at explanation. Only mourning.

All of this reinforces the sense that we are facing one of those rare cases in which the central question is not merely “what happened?” but “in what mental condition did it happen?” In such situations, the justice system moves across deeply uncomfortable terrain: it must determine whether there was conscious intent to kill, or whether the act occurred under a psychological state that compromised the ability to understand reality and the consequences of one’s actions.

This is not about acquittal out of compassion, nor about conviction out of outrage. It is about acknowledging that there are situations in which the boundary between crime and mental illness is not only legal, but profoundly human. A verdict of insanity does not erase the tragedy; it merely changes how society chooses to respond to it. Hospitalization instead of prison. Treatment instead of punishment. And still, the always difficult-to-accept possibility that someone deemed legally insane today may one day be considered fit to live in freedom.

Alan Jackson’s withdrawal on the eve of the hearing resolves nothing. On the contrary, it deepens the sense that this is a case resistant to moral or legal shortcuts. There is a brutal crime. A family destroyed. A defendant with a history of mental illness and addiction. And a justice system compelled to translate all of this into categories such as “intent,” “capacity,” and “responsibility.”

It is still too early for conclusions. But as the case drags on and new layers continue to surface, it becomes clear that this trial will not be only about murder. It will be about the limits of the mind, about the reach of the law in the face of mental illness, and about the kind of truth we are willing to accept when reality itself becomes blurred.

Some cases demand answers. Others, like this one, force us to live with questions that do not go away.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.