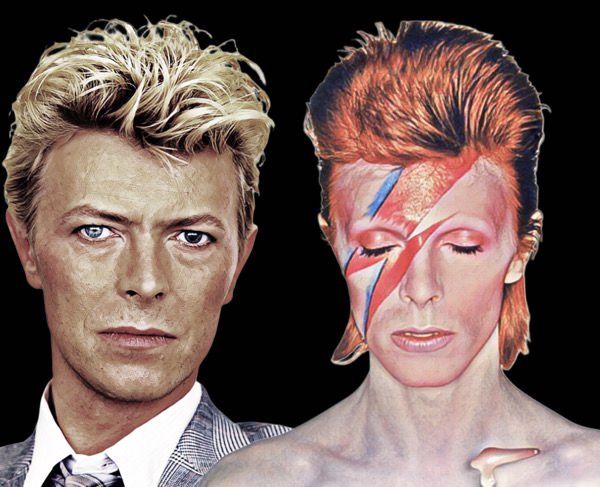

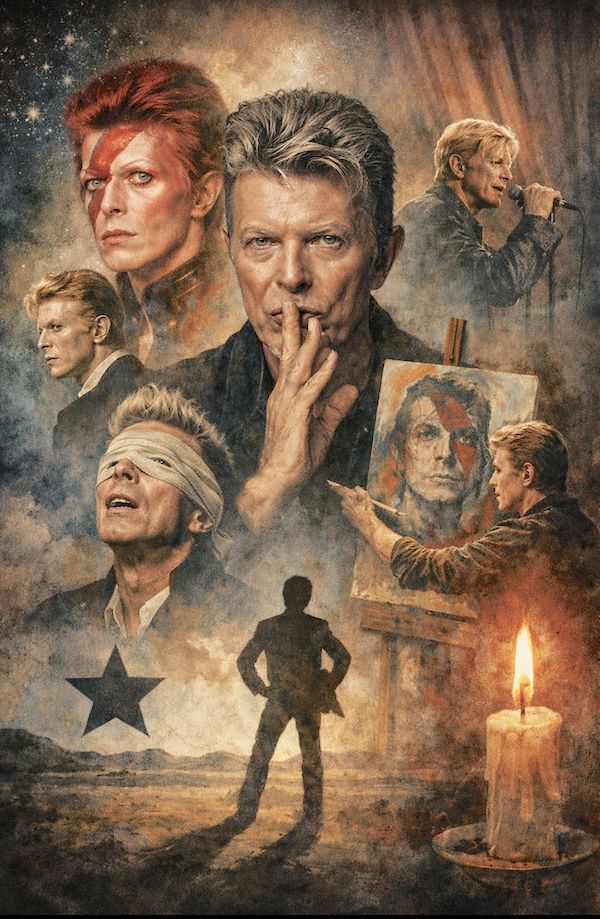

There is no “definitive” David Bowie. There is movement. There is a refusal to remain recognizable for too long. His work does not unfold in a straight line, but as a series of reinventions that converse with the spirit of each era, often anticipating it. Choosing ten songs is not about naming the “best,” but identifying ten moments in which Bowie redefined himself and, in doing so, reshaped the imagination of pop music. Each of these tracks did more than mark a phase: they opened worlds.

“Space Oddity” (1969)

Here, the modern Bowie is born. Major Tom is not merely a lost astronaut; he is pop culture’s first great metaphor for alienation, displacement, and technological loneliness. Released in the year of the Moon landing, the song turns a scientific milestone into existential drama. Bowie establishes his signature: using contemporary events to speak of timeless emotions. Space is not a setting; it is a psychological state. “Space Oddity” introduces the theme that will echo throughout his work—the individual facing forces larger than himself, whether technology, fame, identity, or power.

“Changes” (1971)

If “Space Oddity” introduces the artist, “Changes” explains the method. This is not simply a song about transformation; it is an aesthetic manifesto. Bowie asserts that change is not an accident of the journey but the very essence of his art. Still grounded in piano-driven pop, the song announces what lies ahead: there will be no promise of stability. In “Turn and face the strange,” Bowie legitimizes the unfamiliar, the different, the yet-to-be-named. From here on, his career becomes a conscious sequence of ruptures.

“Starman” (1972)

Ziggy Stardust is not merely a character; he is a cultural gesture. “Starman” turns rock into a message of salvation for a generation that did not recognize itself in traditional models of masculinity, sexuality, and behavior. Bowie appears on British television as a glam alien—ambiguous, seductive, vulnerable—and something changes forever. The song is pop on the surface, almost innocent, yet radical in subtext: there is another way to exist, and it can be beautiful. Here, Bowie does not merely sing; he authorizes identities.

“Life on Mars?” (1971)

If “Starman” addresses the collective, “Life on Mars?” is solitude in close-up. A grand ballad with cinematic harmonic shifts, it turns personal frustration into emotional spectacle. The question in the title is not scientific; it exposes the absurdity of everyday life, media, politics,s and unfulfilled promises. Bowie uses melodrama to speak of modern alienation. The song reveals his ambition beyond rock: he wants to create miniature films in sound, with characters, conflict,ct and catharsis.

“Heroes” (1977)

At the heart of the so-called Berlin Trilogy, “Heroes” may be Bowie’s most universal song. Recorded in the shadow of the Wall, it tells of two lovers meeting in a surveilled, divided, political space. Its power lies in ambiguity: heroism is not grandiose, but momentary, fragile, human. “We can be heroes, just for one day” offers intensity, not eternity. Bowie trades glam spectacle for an emotional ethic—resist, love, exist, even when everything conspires against you.

“Ashes to Ashes” (1980)

Here, Bowie revisits his own myth to dismantle it. Major Tom returns, now as a tragic figure: dependent, lost, an emblem of the illusions of the previous decade. “Ashes to Ashes” is autobiographical without being confessional, addressing addiction, disorientation, and collapse. At the same time, its electronic production points toward the 1980s. Bowie does something rare: he rewrites his own artistic past from within the work, acknowledging error, fragility, and fantasy. There is no nostalgia here—only critical self-examination.

“Let’s Dance” (1983)

Often labeled “commercial,” “Let’s Dance” is in fact Bowie expanding his reach without abandoning symbolic depth. The surface is accessible, irresistible. But the video—depicting racism, poverty,y and inequality in Australia—reveals another layer: pop music as a vehicle for social commentary. Bowie understands the visual power of the MTV era and uses it to speak of exclusion and structural violence. He enters the mainstream to transform it from within.

“Under Pressure” (1981)

Bowie’s collaboration with Freddie Mercury produced one of the most powerful songs about modern anxiety. “Under Pressure” captures the collective experience of a fast, competitive, emotionally exhausted world. It is not a cry of rebellion, but a plea for empathy. Bowie and Mercury do not compete; they converse. The song exposes male vulnerability in a genre historically associated with bravado. It is a portrait of the late 20th century reaching its emotional limits.

“Lazarus” (2016)

Here, Bowie confronts his own mortality with lucidity and form. “Lazarus” is not merely a farewell; it is a work of art about dying in public. Released days before his death, it turns the body into language, pain into poetic construction. There is no self-pity, only awareness. Bowie stages his absence, plays with religious symbolism, and speaks of suffering and transcendence. It is the final gesture of an artist who never separated life from work.

“Blackstar” (2016)

If “Lazarus” is the intimate goodbye, “Blackstar” is the aesthetic testament. Experimental, fragmented, unsettling, the track fuses jazz, electronics, rock, and silence. Bowie does not close his career with a comfortable synthesis, but with a demanding, open, almost enigmatic piece. He dies as he lived artistically: refusing the obvious, stretching form, asking more of the listener. “Blackstar” is not meant to be immediately understood; it asks for listening, rereading, and time.

Why do these ten songs matter?

Because together they form an emotional and aesthetic biography. Bowie was not merely a gifted songwriter or a style icon: he was a thinker of pop culture. He used characters to discuss identity, fame to question power, the body to speak of politics, gender, and mortality. His work does not simply follow its time; it interrogates it. And yet, every rigorous map has its margins of feeling.

Some songs do not enter by historical criterion, but remain through memory. “Absolute Beginners,” like “Modern Love,” may not represent a major aesthetic turning point, but it stands as one of the most passionate love songs in his catalogue: romantic, cinematic, unmistakably of the 1980s. For those who lived that decade, it carries an emotional weight that cannot be measured in cultural impact alone, but in lived experience. To mention it here is not a method; it is affection. Because, in the end, Bowie also taught us this: that art is made not only of ruptures and manifestos, but of what moves us personally and endures.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu