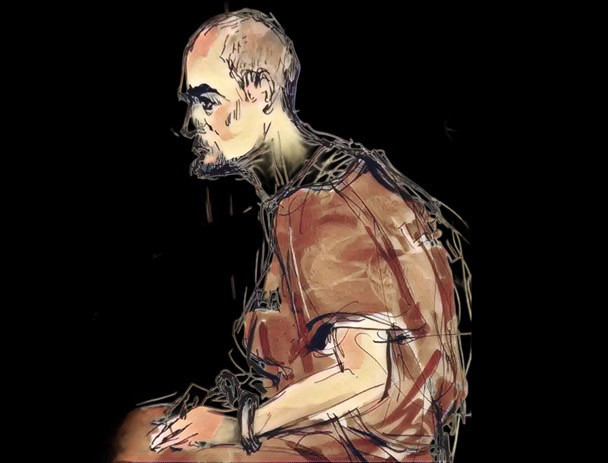

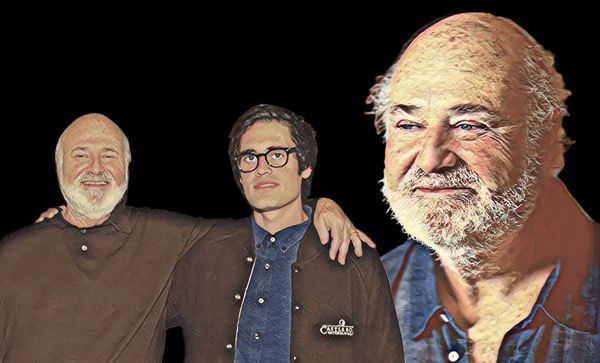

Few moments in a criminal case are as revealing as a lawyer’s abrupt exit on the eve of a court hearing. In the case of Nick Reiner, accused of killing his parents, Rob and Michele Reiner, Alan Jackson’s withdrawal was not a procedural footnote. It reshaped the public narrative of the case and exposed, if only between the lines, the limits of the defense strategy that had been taking form.

Jackson is no ordinary name. A high-profile criminal defense attorney known for handling complex cases and advancing aggressive legal theories, he asked the judge to relieve him from representation just moments before the hearing, stating that he had “no choice” but to withdraw. In legal language, such phrasing is rarely casual. When a lawyer of that stature steps away, what is usually inferred behind the scenes is a convergence of factors: an irreconcilable conflict with the client, strategic disagreements over the direction of the defense, ethical concerns about advancing a particular theory, or even practical impasses involving cooperation, access to information, or resources.

What has been circulating in legal circles is that Jackson had been preparing a defense anchored in a plea of “not guilty,” but not in the most literal sense of simply denying the act. The strategy was reportedly aimed at constructing a narrative capable of introducing reasonable doubt regarding authorship, intent, or even the defendant’s capacity to be held criminally responsible. That is where the scenarios that began to gain traction come into play: mental health, the possibility of third-party responsibility, or even the idea of an unidentified perpetrator.

The first avenue, and perhaps the most predictable in cases of this nature, is mental health. This does not automatically mean an insanity defense, which in the United States is narrowly defined and rarely successful, but rather an argument that the accused lacked full capacity to understand or control his actions at the time of the crime. Such a strategy does not necessarily seek outright acquittal; it can open the door to mitigation, a reclassification of charges, or, in some cases, psychiatric commitment rather than prison. The difficulty is that this approach requires substantial clinical documentation, independent expert evaluations, and, crucially, the defendant’s willingness to undergo scrutiny and accept that his mental condition becomes the central axis of the case. When there is resistance from the client, the family, or internal disagreement over how far to pursue this path, conflict with counsel is almost inevitable.

The second possibility is to shift responsibility to a third party, suggesting that Nick was not the perpetrator. This is the most legally precarious line of defense because it demands more than casting doubt; it requires presenting a plausible alternative narrative, supported by material evidence, inconsistencies in the investigation, or breaks in the chain of custody. Evoking “another responsible party” or even the notion of a “killer still at large” can be powerful in the court of public opinion, but in an actual courtroom, it only holds if there are concrete elements capable of dismantling the prosecution’s case. Without that foundation, such a theory tends to collapse and weaken the defense’s overall credibility.

There is also a more subtle layer: the possibility that Jackson encountered ethical limits. Attorneys cannot knowingly present false narratives or pursue a defense that violates fundamental professional standards. When such an impasse arises, formally withdrawing from the case becomes not only strategic but necessary.

With Jackson’s departure, Nick is now represented by Kimberly Greene, a public defender with the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office. This shift is not merely a change of name but a change of logic. Public defenders operate within a different structure, with different resources and, above all, a different relationship to the system. Greene does not step into the case to sustain a media-driven narrative; she enters to safeguard the constitutional right to defense, to scrutinize the record, review the prosecution’s case line by line, and determine, based on what is legally viable, which path to pursue.

That may mean a complete reassessment of strategy. If a “not guilty” theory rests on fragile ground, it may be reworked. If there is room to argue diminished capacity or mental health issues, Greene can seek formal evaluations and present that axis in a technical, unsensational manner. And if the prosecution’s evidence proves particularly strong, it would not be surprising to see an examination of plea negotiations, charge reductions, or other procedural avenues that, while less dramatic, are part of the reality of serious criminal litigation.

The next steps, therefore, are less cinematic and more procedural. First, the new defense must obtain full access to the case file and investigative materials. Then comes the crucial decision on the official posture: whether to maintain the “not guilty” plea as originally framed, to recalibrate it around mental health or another legal theory, or to signal openness to negotiation. It is also likely that the court will revisit scheduling, as a change in representation often justifies delays in complex cases.

What makes this case particularly fraught is the intersection of family tragedy, mental health, and intense public scrutiny. The departure of a prominent attorney is not, in itself, proof of anything, but it is an indication that the defense was facing real constraints. The arrival of Kimberly Greene marks the beginning of a less spectacular but more consequential phase: it is now, away from easy headlines, that the narrative will be defined — whether it becomes one of incapacity, of reasonable doubt regarding authorship, or of full criminal responsibility.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.