I warned you: the season has barely begun and already feels repetitive. BAFTA’s longlist confirms what other awards have been signaling since December — the same titles, the same names, the same geometry of power. Still, it would be a mistake to dismiss the British prize as a mere formality. BAFTA may be predictable, but it is rarely neutral. It organizes the board, legitimizes favorites and, from time to time, anticipates turns that Hollywood is still reluctant to see.

Recent history helps explain this paradox. In 2023, BAFTA crowned Cate Blanchett for Tár, going against the wave that ultimately carried Michelle Yeoh to the Oscar. It was a “European” reading, sophisticated, consistent with the British academy’s taste, but one that did not hold in the final stretch of the season. Last year, however, the award surprised everyone by giving the prize to Mikey Madison when nearly all expectations pointed to Demi Moore. It was not just a gesture of distinction: it was a prescient call. Madison went on to win the Oscar, and BAFTA emerged as the body that saw it first.

It is within this balance between conservatism and strategic instinct that the 2026 edition takes shape.

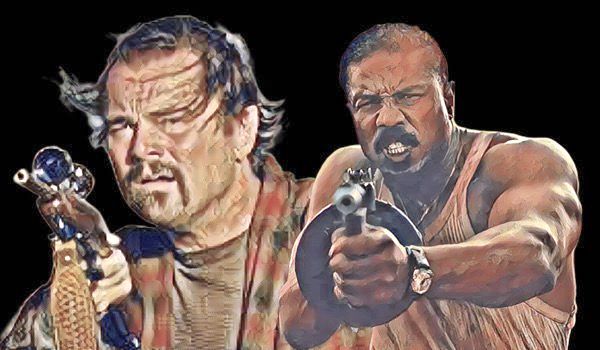

At the center of the race are, once again, the films that already dominate the narrative. One Battle After Another leads comfortably and occupies the familiar role of “the film to beat”: ambitious, politically charged, with strong auteur credentials and a prestige cast. Leonardo DiCaprio stands as the most visible face of the project, and once again as a natural candidate to embody the “performance of the year.” On the other side is Sinners, by Ryan Coogler, which combines cultural impact, box-office power, and a Michael B. Jordan in full star mode. These are two distinct forms of prestige: the authority of the “important” film and the force of the movie that imposes itself on the public conversation.

The male acting race also runs through Timothée Chalamet. Marty Supreme places him in a different key from DiCaprio: less institution, more reinvention. Chalamet is not merely a favorite; he is the face of a generation that BAFTA consistently tries to legitimize without appearing captive to fashion. If the prize goes his way, the gesture will be less about consecration and more about the future. DiCaprio represents the canon. Chalamet, the long-term bet.

On the female side, the list reveals an intriguing contradiction. While American awards have been overlooking Cynthia Erivo, BAFTA makes a point of recognizing her for Wicked: For Good. This is no small detail: it signals that the British academy still allows itself to value performances that have not entered the Hollywood consensus. Alongside her are names such as Jessie Buckley, Renate Reinsve, Emma Stone, and Jennifer Lawrence, a lineup that blends auteur respect, critical prestige, and market recognition.

Yet it is in the British block that BAFTA most clearly reveals its role as a national showcase, and where its distance from American awards becomes most evident.

In Dragonfly, Brenda Blethyn portrays an elderly woman living in a rural English community, in a quietly observed drama about aging, solitude, and silent resilience. It is a role built in the tradition of British realism: few outbursts, deep interiority, a kind of acting that rarely drives Oscar campaigns but that BAFTA has historically valued. Blethyn is not there as a “quaint supporting player” of the season: she represents a school of performance that British cinema refuses to abandon.

I Swear operates in a different register. The film follows a young man entangled in a legal case that exposes tensions of class, masculinity, and morality in contemporary England. Robert Aramayo delivers a restrained, anxious performance, shaped by silences and micro-gestures, a style more closely aligned with British theater and television than with the emotional rhetoric that tends to appeal to the American Academy. BAFTA embraces him as a “serious actor,” even as Hollywood barely takes notice.

In Pillion, Harry Melling takes on an uncomfortable, ambiguous, almost anti-charismatic character in a drama that explores power, sexuality, and marginality. It is a risky performance that deliberately avoids easy empathy, precisely the kind of choice celebrated in European circuits, but rarely translated into awards narratives in the United States.

Perhaps the most emblematic case is The Ballad of Wallis Island. Set on a remote island, the film is a melancholic story about characters suspended between memory, belonging, and the feeling of being out of time. Carey Mulligan appears in a register opposite to her most “awards-friendly” roles: less grand, more ethereal, sustained by atmosphere and presence. It is a work of emotional precision, deeply British in its restraint, and therefore poorly aligned with the more explicit tastes of American campaigns.

These titles and performances help explain why BAFTA, though predictable at its core, is not simply a replica of the Oscars. It reaffirms a prestige circuit that values intimacy, moral ambiguity, and the tradition of British realism, even when such work fails to cross the Atlantic as awards-season currency.

None of this means the prize is willing to fully subvert the season. On the contrary, the overall design is safe. One Battle After Another and Sinners concentrate most of the bets. DiCaprio, Chalamet, Jordan, Stone, Lawrence. Everything recognizable, everything “where it should be.” Predictability, in this sense, is not an occasional flaw: it is a method.

But that is precisely where BAFTA remains relevant. It does not decide the Oscars, and sometimes it errs with elegance, as in the Blanchett-versus-Yeoh year. At other times, however, it gets it right when few dare to, as with Mikey Madison. It functions less as a mirror of the American industry and more as its counterpoint: it confirms trends, but also tests limits; it legitimizes consensus, but leaves clues as to where the season might still turn.

In 2026, the picture is clear. One Battle After Another and Sinners dominate the landscape. DiCaprio and Chalamet are not merely competing for a trophy, but for two different ideas of stardom. Cynthia Erivo finds at BAFTA a recognition that Hollywood denied her. And British actors — Blethyn, Aramayo, Melling, Mulligan — once again occupy a space of prestige that does not depend on American validation.

The list is predictable, yes. But it is not irrelevant. As always, BAFTA does not write the ending of the story — it organizes the plot. And sometimes, it reveals who is being positioned for the final act.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.