Ten years after his death, on January 10, 2016, David Bowie should not merely be remembered; he should be celebrated. He is to be revisited, reinterpreted, rediscovered. Few artists withstand time in this way: not as static monuments, but as forces still in motion. To speak of Bowie is not to list hits; it is to map cultural shifts. Here are ten facts that help explain why he remains one of the most decisive figures in modern art.

1. Bowie turned identity into artistic language.

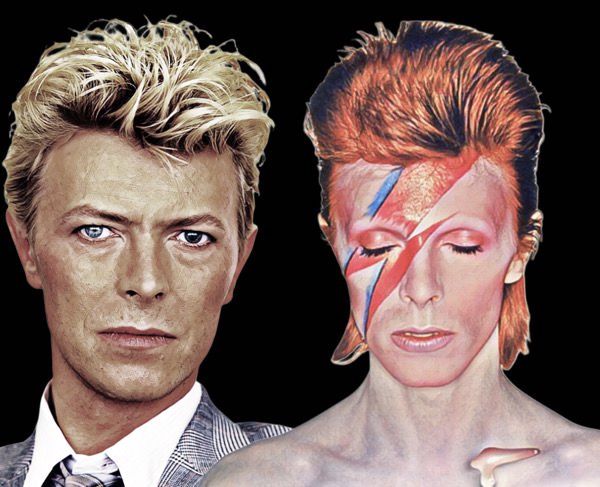

Long before discussions of gender, performance, and identity dominated cultural debate, Bowie was already using his own body as a field for aesthetic experimentation. Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke: they were not characters in a merely theatrical sense, but artistic devices for exploring desire, alienation, fame, and ambiguity. He did not simply sing about transformation—he embodied it. For generations seeking permission to exist outside the norm, Bowie became proof that identity itself can be creation.

2. He redefined what a pop artist could be.

Bowie never accepted the comfortable role of the predictable idol. Each phase dismantled the previous one: from folk to glam, from soul to electronics, from Berlin-era experimentation to the sophisticated pop of the 1980s. Instead of protecting a brand, he sabotaged it. This refusal to repeat himself created a new model of artistic career: non-linear, not bound to a single style, open to risk. Without Bowie, it is hard to imagine trajectories such as Madonna’s, Radiohead’s, Björk’s, or Lady Gaga’s.

3. He helped legitimize rock as conceptual art.

Albums like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Station to Station, and Low are not merely collections of songs, but works structured by ideas. Bowie brought elements of theater, literature, visual art, and philosophy into the rock mainstream. Popular music ceased to be only entertainment and became an aesthetic project. Today, when we speak of “eras” and “concepts” in pop, we are speaking of a legacy he helped create.

4. His Berlin period changed the course of contemporary music.

Between 1976 and 1979, Bowie produced the so-called “Berlin Trilogy” (Low, “Heroes”, Lodger), incorporating electronic music, ambient, krautrock, and structural experimentation. What seemed strange and fragmented at the time became the foundation for post-punk, electronic music, indie, and art rock in the decades that followed. Joy Division, Depeche Mode, Nine Inch Nails, Arcade Fire: all of them dialogue with that moment when Bowie chose to go against the market to reinvent musical language.

5. In the cinema, he was far more than a singer trying to act.

Bowie did not seek roles simply to “appear”; he sought characters that conversed with his artistic persona and with themes of identity, power, and displacement. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, he became the very image of modern alienation. In Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, his performance as the British prisoner Jack Celliers is perhaps the most impressive of his career: restrained, physical, silent, built far more through gaze and presence than through dialogue. Nagisa Oshima’s film turns Bowie into a political body, a symbol of cultural clash, repressed desire, and confrontation between irreconcilable moral codes. This is not “a singer doing cinema”; it is an actor who understands the character as a metaphor.

In The Hunger, he blends eroticism and melancholy with rare sophistication; in Labyrinth, he creates a pop icon for an entire generation; and in The Prestige, his portrayal of Nikola Tesla encapsulates the visionary Bowie: a man ahead of his time, misunderstood, yet decisive. In all these appearances, he brought to the cinema the same logic he brought to music: the character as an extension of artistic thought.

6. He changed the history of fashion by turning style into discourse.

Bowie did not “follow trends”; he created them. Makeup, hair, androgynous silhouettes, Kansai Yamamoto costumes, references to kabuki, expressionism, and haute couture: everything was part of a visual narrative. By blurring the boundaries between masculine and feminine at the height of the 1970s, he opened paths for fashion and behavior to become political rather than merely decorative. The impact remains visible today on runways, in editorials, and in the very idea of fashion as performance.

7. His relationship with visual art was structural, not ornamental.

Bowie did not merely collect art; he thought like a visual artist. A student of expressionism, surrealism, and contemporary art, he painted, drew, and incorporated visual references into the construction of his albums, videos, and covers. He understood image as narrative, not as packaging. In a world increasingly dominated by the visual, Bowie anticipated the figure of the multimedia artist—for whom sound, image, body, and concept form a single work.

8. He redefined the artist as a cultural curator.

Bowie did not only create; he pointed the way. By championing and amplifying artists such as Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Kraftwerk, Placebbo and Arcade Fire, he acted as a mediator between the underground and the mainstream. His taste, his lists, his interviews, and his side projects helped legitimize movements and careers. In a time before social media, Bowie already exercised the role of “curator”—someone who not only produces, but organizes and expands the cultural field.

9. His work consistently engaged with the spirit of its time.

Alienation, technology, surveillance, identity collapse, celebrity as simulacrum: themes that today seem central were already present in Bowie decades ago. Songs such as “Ashes to Ashes,” “Heroes,” “I’m Afraid of Americans,” and “Blackstar” have not aged because they speak less to a specific era than to a modern condition. Bowie did not merely document the present; he interrogated it. That is why his music still sounds uncannily current.

10. He turned his own death into a final artistic gesture.

Blackstar, released two days before his death, is not merely an album; it is an aesthetic testament. Bowie faced finitude with the same lucidity with which he confronted fame, identity, and creation. By making farewell itself into a work, he reaffirmed something rare: art as a form of thought until the very last moment. Few artists have managed to close their own trajectory with such coherence and symbolic power.

Ten years on, Bowie is not simply a great name from the past. He endures as method, as attitude, as horizon. More than an artist who influenced styles, he taught that culture moves forward when someone has the courage not to repeat themselves, not to over-explain, and to treat existence itself as language. That is why Bowie is not merely remembered. He is still happening.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.