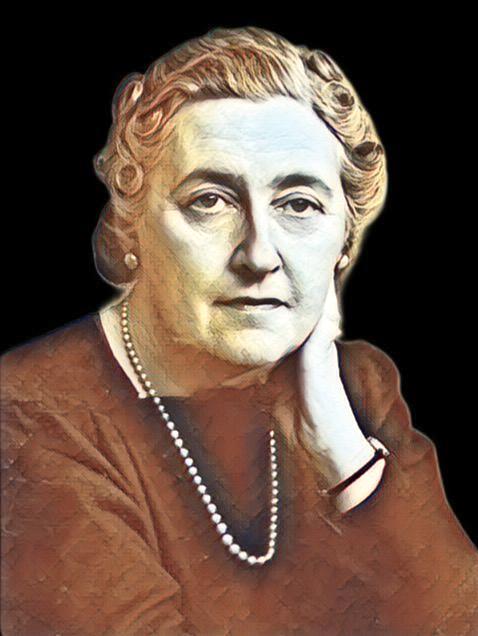

Today marks 50 years since the death of Agatha Christie, and the date calls for more than tribute: it calls for reading. Few bodies of work age with the serenity of those that do not depend on effect but on structure, and few authors have built a language so recognizable without ever becoming repetitive. Christie was not merely the “Queen of Crime”; she was the engineer of a genre, someone who understood early on that mystery is not about piling up clues, but about organizing the reader’s experience, rationing information, hiding what matters in plain sight, and, at the right moment, reshaping what seemed definitive.

Who Agatha Christie was before she became Agatha Christie is part of the charm and the logic of her writing. Born in 1890 in Torquay into a comfortable middle-class family, educated at home, and an avid reader from an early age, she grew up in an environment that encouraged imagination, observation, and a certain taste for games of logic. What is rarely emphasized is how this informal education left her free from literary schools and passing fashions, allowing her to build, almost intuitively, her own narrative method. The world she would later observe, of social conventions, country houses, train journeys, hotels,s and drawing rooms where civility conceals conflict, was already, in some way, present in her youth.

Christie began writing relatively late, prompted by a wager with her sister during the First World War. Working first as a nurse and later in a hospital dispensary, she came into direct contact with chemicals and poisons, an experience that would permanently mark her work. This is not merely a curious biographical detail but an aesthetic key: by choosing poisoning as a recurring method, she transformed crime into something silent, intimate, te and deeply psychological. In Christie, death is rarely spectacular; it is almost always domestic, discreet, and embedded in routine, which makes the mystery all the more unsettling. Evil, in her books, does not come from outside; it infiltrates.

Her encounter with the crime genre was not accidental, but neither was it academic. Christie read Conan Doyle and G. K. Chesterton, absorbed the pleasure of the puzzle, and realized there was room there for rigor and invention. What she added wasa method. The famous “whodunit” in her hands ceases to be merely a question and becomes a narrative architecture. Each character is a possibility, each dialogue a clue that can both reveal and mislead, each scene a piece that must fit at the end. The perfection of her formula lies not in the trick, but in the honesty of the game: all the necessary information is before the reader, and yet the ending still surprises. Christie does not cheat; she organizes.

This organization bears unmistakable authorial marks. Poisons, as a technical signature, coexist with twists that rewrite what has already been read without denying what has been shown. The effect is not gratuitous shock, but belated recognition: we realize we were looking in the right place without knowing how to see. It is a kind of narrative intelligence that respects the reader, because it invites participation rather than passive consumption. In a market often dominated by mysteries that confuse complexity with confusion, Christie’s clarity remains a lesson.

Her detectives are perhaps the most popular aspect of her legacy, but also the most sophisticated. Hercule Poirot, with his obsession with order, detail, and his “little grey cells,” is less a policeman than a walking method: he believes truth is a matter of observation and logic, but also of understanding human motives. Miss Marple, in turn, is the quiet subversion of the investigator archetype. Underestimated, seemingly naïve, she solves crimes by analogy, reading behavior as one reads social patterns. It is no accident that, over the decades, Marple has become a symbol of female intelligence operating at the margins of formal power. Christie wrote detectives who not only solve crimes butalso embody different ways of knowing the world.

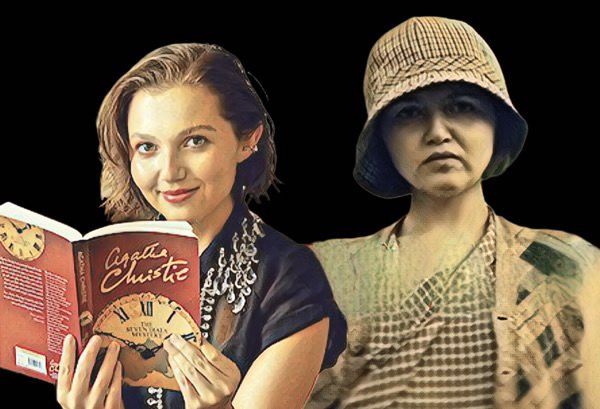

There is also the episode that turned her own life into a mystery: her disappearance in 1926. After her mother’s death and the collapse of her marriage, Christie vanished for eleven days, leaving the country in suspense. She was found in a hotel, under another name, without offering a clear explanation. The episode generated theories, biographies, novels, adaptations, and an aura of enigma that, ironically, brought the author closer to her own plots. More than a sensationalist anecdote, the disappearance reveals the human fragility behind the public figure and perhaps explains why her books, even when playful, are never cynical: there is always an acknowledgment of pain, of loss, of what moves someone to cross a line.

Fifty years after her death, Agatha Christie’s legacy is not only literary; it is institutional. Her estate, now managed by heirs and a dedicated team, controls rights, authorizes adaptations, protects the integrity of the works, and, at the same time, understands that keeping Christie alive requires reinvention. New editions, audiobooks, translations, stage plays, films, and series coexist with a growing effort to contextualize the author for contemporary readers without erasing the marks of her time. The stewardship of the legacy is, in itself, an exercise in balance between preservation and renewal, something rare in cultural heritages of such scale.

It is within this context that the new Netflix series, Agatha Christie’s Seven Dials, adapted from The Seven Dials Mystery, takes shape, revisiting Christie’s universe with a contemporary aesthetic while preserving the heart of the classic enigma. By reimagining Lady Eileen “Bundle” Brent for a new generation and embracing a visual style that dialogues with today’s pop culture, the production does not attempt to “correct” Christie but to translate her into another language and another time, keeping intact what has always been essential: the game of suspicions, the choreography of clues, the twist that reorganizes everything.

Mentioning Seven Dials on a date like today is not merely updating the legacy, but confirming the obvious: Agatha Christie does not belong to the past. Her enigmas still work because they are, above all, human. They speak of jealousy, inheritance, resentment, ambition, guilt, love, and everything that crosses eras with only minor changes of costume.

To mark the 50th anniversary of Agatha Christie’s death is to recognize that few authors have so profoundly shaped the way we read, watch, ch and think about crime stories. She turned mystery into form, curiosity into methand od, and entertainment into rigor. In a world saturated with narratives that bet on excess, her lesson remains elegant: true suspense is not in noise, but in order. And as long as readers are willing to follow clues, distrust the obvious, and accept the invitation of an honest narrative game, the Queen of Crime will continue to reign, discreet and implacable, over every “whodunit” that still challenges us.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.