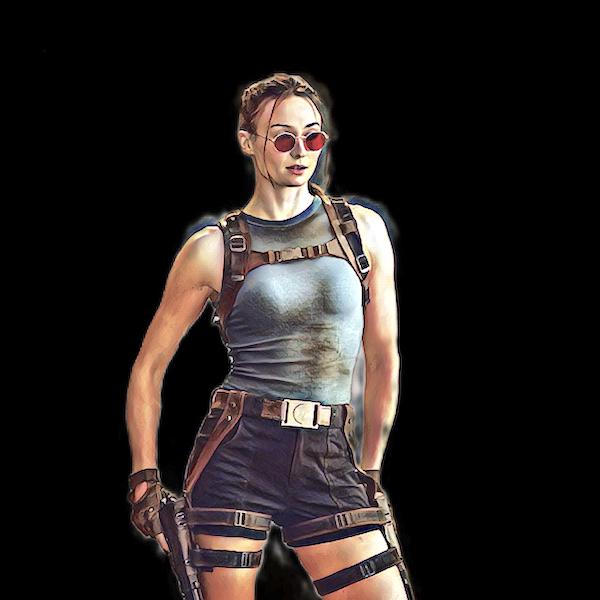

Expectations were growing, and the official image seems promising: Sophie Turner is now Lara Croft in Amazon Prime Video’s version.

Some characters do not belong to a specific era because they endure and cannot be exhausted by a single interpretation. Lara Croft is one of them. Since her emergence in the 1990s, her image has been consistently contested: between strength and fetish, between myth and humanity, and between spectacle and character. Every new adaptation feels less like a conclusion and more like another chapter in a recurring question: who, after all, is Lara Croft for her time?

The character’s origin helps explain why that question never disappears. Created in 1996 in the first Tomb Raider, Lara was a rupture within the gaming industry itself. A female protagonist, independent, adventurous, intellectually autonomous, who turned archaeology into a language of action and space into narrative. At the same time, she carried the visual and commercial marks of the decade: hypersexualization, unrealistic proportions, and an iconography designed as much to fascinate as to provoke. From the beginning, then, Lara existed as a paradox: a symbol of female power and a product of a culture that did not yet know how to represent that power without reducing it to the surface.

When cinema encountered her in the early 2000s, the choice was to embrace the myth. Angelina Jolie’s Lara was not built as a person but as an image. Jolie brought charisma, physical magnetism, and a presence that turned the character into an instant pop icon. Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001) was a major box-office success and definitively established the archaeologist in the global imagination. The problem was never the actress, but how cinema chose to use her. The stories were shallow, the villains were generic, and mythology was treated as a mere pretext. Lara was larger than her own films. The sequel, two years later, quickly revealed the formula’s fatigue. Jolie had created a symbol, but cinema had still not created a character.

Nearly two decades later, the next attempt moved in the opposite direction. In 2018, with Alicia Vikander, the discourse was realism. The new Lara was younger, less idealized, more physical, vulnerable, in formation. There was an important ethical and aesthetic correction: less fetish, more body, more exhaustion, more failure. Vikander gave credibility to the effort, making Lara someone who bleeds, falls, and hesitates. The film was received with respect, but without enthusiasm. It did not fail, but it also did not generate a desire for continuity. What was missing was narrative personality, a mythology of its own, a voice. Vikander’s Lara became a person, but she still did not become a story.

It is in this space between image and humanity that the new attempt takes shape. Lara Croft now returns not merely as a reboot, but as a long-form project, in series format, at a moment when streaming platforms are searching for characters capable of sustaining universes, not just recognizable titles. The Last of Us and The Witcher proved that video games can generate prestige, debate, and density when treated as narrative rather than brand. Tomb Raider returns because, despite its omnipresence in the cultural imagination, it has never been fully resolved on screen. The character remains open, unfinished, in permanent dispute over meaning.

The choice of Sophie Turner as the new Lara points neither to the untouchable myth of Jolie nor to the physical minimalism of Vikander. It points tothe process. Turner brings a public image associated with maturation, trauma, displacement, and reconstruction, qualities that resonate with the more recent phases of the games. She is not a star who eclipses the role, nor a neutral presence. She carries a generation of viewers who watched her grow in Game of Thrones, learning to sustain long, ambiguous, emotionally complex arcs. The expectation surrounding her Lara is neither of a fetishized heroine nor merely a grounded one, but of a character with psychological density, internal conflict, and dramatic continuity.

Her experience with franchises helps clarify both the risk and the bet. Game of Thrones was her formative work in serialized universes, where she learned to build a character over years, in layers, without shortcuts. X-Men, especially Dark Phoenix, was the opposite experience: a complex icon compressed into a project without time, focus, or identity, whose failure was less personal than structural. Turner knows, therefore, the weight of carrying a symbolic character and the danger of doing so without a solid narrative architecture. Tomb Raider becomes her third major franchise, but the first in which she does not enter merely as an interpreter of a pre-established system, but as the face of a project designed to endure.

What truly reorients this new phase, however, is who writes Lara. For the first time in live action, the character is born under a clear authorial signature: Phoebe Waller-Bridge, as creator, writer, executive producer, and co-showrunner. Waller-Bridge is not an architect of conventional action. Her strength lies in voice, in the construction of contradictory characters, in the tension between control and vulnerability, in the dry humor that does not dilute pain but exposes it. By taking on Tomb Raider, she signals a shift in axis. After two eras in which cinema tried to resolve Lara through image or physicality, the promise now is point of view. This is not merely about updating the character, but finally writing her.

The ensemble that surrounds Turner reinforces that ambition. Sigourney Weaver appears as a figure of ambiguous authority, someone who embodies power, strategy, and potentially sophisticated antagonism. Jason Isaacs connects Lara to a dimension of inheritance and family past, introducing the idea of legacy as conflict rather than comfort. Characters tied to museums, government, and institutions introduce an ethical layer: who holds the right to history, to artifacts, to memory? At the same time, the presence of allies drawn from the franchise’s mythology and of direct rivals sketches a universe of continuous relationships rather than isolated adventures. The Lara of this series does not merely run and fight; she collides with systems, with interests, with her own past.

The first official images of Sophie Turner in character distilled this transition. There was neither shock nor easy nostalgia. Recognizable elements of Lara’s iconography were there, but without the fetishistic stylization of earlier eras. The reaction was one of cautious curiosity, almost relief: recognition without caricature. It was not about recovering a fantasy, but about signaling a plausible character. Perhaps the most promising sign was not immediate enthusiasm, but genuine interest. For the first time in a long while, the conversation did not revolve solely around how Lara looks, but around what this version intends to say.

Angelina Jolie turned Lara Croft into a symbol. Alicia Vikander tried to turn her into a person. Sophie Turner, under the creative command of Phoebe Waller-Bridge, has the chance to turn her into a narrative. Lara has always returned because she has never been fully resolved on screen. In 2026, she comes back not as a mere icon to be reactivated, but as a character finally to be written. If this new phase succeeds, it will not be just another reinvention. It will be the moment when the most famous archaeologist in pop culture ceases to be only an image, body, or brand and becomes, at last, a story.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.