It cannot be easy to work with Stephen King or George R. R. Martin. They are not merely award-winning authors or global best-sellers: they are architects of worlds, creators of mythologies that cut across generations and cultures. Cinema — and now the platforms — is obsessed with them for precisely that reason. But that obsession is rarely simple. It produces a torturous relationship, marked by admiration, frustration, and, almost always, conflict.

Neither King nor Martin became screenwriters in the same way they became giants of literature. Their books are the territory in which they exercise absolute control over tone, structure, and moral ambiguity. When their work migrates to the audiovisual realm, that control necessarily dissolves: producers, budgets, schedules, audiences, and market strategies enter the picture. It is therefore no surprise that both view with suspicion those who must alter their storiestoo bring them to the screen. This is not mere vanity, but a deeper dispute over authorship: to what extent does a work remain “yours” once it becomes a collective product?

Because both authors have always been public about their criticisms, the result is a long record of exposed frictions, interviews tinged with resentment, and statements that feed the sense that no adaptation is ever fully sufficient. What often remains is this constant noise: a succession of disagreements that becomes a narrative in its own right. Not because they despise the audiovisual medium, but because, when they see their worlds reconfigured by other hands, they are forced to confront the most painful side of fame: the moment when creation ceases to be merely a work and becomes contested territory.

For this reason, the backstage drama surrounding Martin’s adaptations has ceased to be mere speculation and has become part of the story itself. Epic battles now take place off-screen, through declarations charged with authorial authority and a constant — not always positive — anticipation of what will reach the public. What might otherwise be dismissed as industrial noise is absorbed into the very mythology of the series.

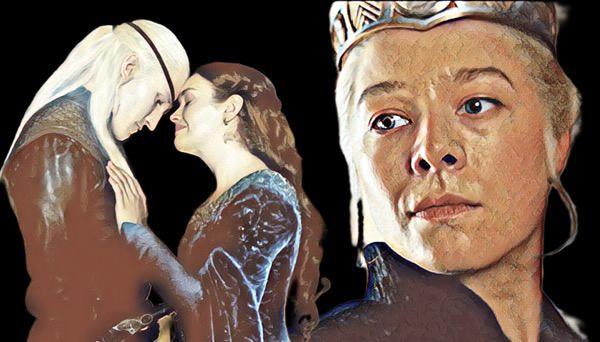

Whether on his personal blog or in interviews, Martin’s frankness — today openly dissatisfied with House of the Dragon — does the production few favors. The prequel did not provoke the near-unanimous rejection that marked the end of Game of Thrones (about which, tellingly, the author never offered direct criticism), but as it advances toward its third season — the penultimate one — it remains far from achieving the cultural impact of the original. What is left is a work crossed by public disputes over authorship, in which each episode carries not only the story of Westeros, but the weight of a creator who no longer fully recognizes himself in what airs.

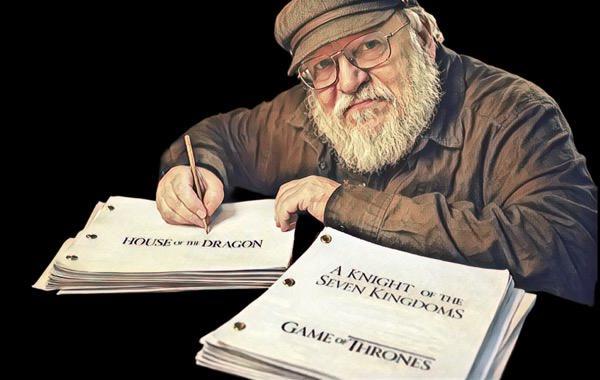

Thus, some interviews function as involuntary confessions. George R. R. Martin’s long conversation with The Hollywood Reporter is not merely a portrait of a celebrated author at seventy-seven; it is a document about the cost of turning a work into a universe, a writer into a brand, and a story into a franchise. The headline gets it right: the crown is heavy. But the weight here is not only fame. It is the contradiction that has accompanied Martin for more than a decade: he built an empire that depends on the world he created, while that very empire seems to drain the time, energy, and solitude required to complete the work that gave birth to it.

The text returns to the past, when Martin still feared becoming a Hollywood “one-hit wonder” and dreamed of a mythology that could survive for generations. That wish was fulfilled on a massive scale. Westeros expanded into series, games, stage productions, animation, projects in development, and physical ventures that reshape Santa Fe itself: a bookstore, a cinema, a bar, a themed train, and cultural investments. Martin did not merely write a world; he turned it into an ecosystem. The paradox is evident. The author who feared disappearing as a creator became an institution, but he pays for it with fragmented focus. His career is now a sum of open fronts, meetings, production decisions, creative disputes, and external expectations. The writer who wanted time to write became, in practice, a manager of legacy.

The interview makes clear that Martin views this success with pride, but also with a kind of moral fatigue. He did build the empire — and the verb matters — yet he does not sound entirely comfortable within it. When he speaks about A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms, his new HBO project, his satisfaction comes from its modesty: “smaller,” “more contained,” without dragons or colossal battles, as if simplicity itself were a creative relief. It is telling that, at the height of his media expansion, what gives him pleasure is a return to the intimate: two characters, a road, conversations, humor, heart. As if, after erecting a global mythology, Martin were seeking refuge precisely in the human scale that has always been the emotional engine of his writing.

But the emotional core of the interview is not the new series. It is The Winds of Winter. The book has become — for readers and for Martin himself — not merely a project, but an open wound in time. He speaks of it with a mixture of shame, stubbornness, and anticipatory grief. He does not deny the pressure; he feels its weight. The WorldCon episode, in which a fan suggested that another writer should finish the work because he “won’t be around much longer,” is described as a kind of symbolic violence. It is not only rudeness; it is the reduction of an entire creative life to an expiration date. Martin’s response — “nobody needs that” — resonates beyond the anecdote. There is here a bitter reflection on how fan culture, shaped by industrial schedules and serialized consumption, can turn expectation into moral pressure.

At the same time, Martin does not absolve himself. He acknowledges that the success of Game of Thrones was, paradoxically, the best and the worst thing that ever happened to his work. Fame brought resources, platforms, and influence, but also dispersion, interference, negotiation, and frustration. When he describes his writing process — opening a chapter, hating it, rewriting, jumping from Tyrion to Jon, pulling back because a solution would “change the whole book” — what emerges is not a writer blocked by laziness, but a creator trapped by a vast structural ambition. A Song of Ice and Fire has become a narrative organism so complex that every choice reverberates across dozens of dramatic lines. What was once an aesthetic virtue — multiple viewpoints, moral ambiguity, intricate architecture — has become a minefield when it comes time to end.

The interview also reveals, with rare frankness, Martin’s conflict with the adaptation of House of the Dragon. His “abysmal” relationship with showrunner Ryan Condal is less a backstage scandal than a symptom of something deeper: the difficulty of watching one’s “children” rewritten by others under the pressures of budget, production, and audience. Martin frames fidelity as an ethical principle of adaptation. When he says his characters are his children, he is not speaking only of emotional attachment, but of creative authority. The friction with HBO, the deleted posts, and the statement “this is no longer my story” expose the limits of authorship within an industrial system. Westeros may legally belong to Warner Bros., but for Martin it remains intimate territory. The fracture between creator and machine is one of the most revealing tensions in the piece.

That said, I will admit that I agree with Martin on many points, especially when it comes to House of the Dragon. On the page, the story already seemed ready for the screen: it did not require the changes the series has introduced, much less those still to come. But the very word “adaptation” anticipates the problem. It never means “transfer.” It is not copying, not mirroring, not absolute fidelity. It is a translation between languages, and every translation implies loss, choice, and rewriting. It is in this gray zone, between the work as it was written and the work that must exist as an audiovisual product, that the discussion becomes both more complex and harder to judge.

Perhaps the most moving passage is the one in which Martin speaks of the deaths of colleagues and idols, culminating in the episode with Robert Redford, who improvised the line “George, the whole world is waiting, make a move”, and died shortly thereafter. The scene functions almost as a metaphor: the unfinished work, finite time, and an acute awareness of mortality. There is no sentimentality here, only a brutal recognition that posterity is not guaranteed by fame, but by what one manages to complete. When Martin says that handing the book to another writer “is not going to happen” and that, if he dies, the work will remain unfinished as Dickens left The Mystery of Edwin Drood, he affirms a nearly tragic authorial ethic: finishing is part of the integrity of creation. Not finishing would, for him, be “a total failure.”

And yet there is a piercing irony at the interview’s close. Martin imagines darker endings than the series delivered, considers killing Sansa, insists that he sees no “happy ending for Tyrion,” and still admits that he does not yet know exactly how everything ends. The author who taught the world to distrust easy resolutions finds himself trapped by the very problem of the ending. The crown is heavy because it demands closure, coherence, and legacy. And perhaps because Martin, who always wrote against the comfort of tidy conclusions, must now offer a final chapter to a public that has grown up, grown older, and waits — with impatience, but also with love.

What emerges is neither the portrait of a capricious genius nor that of a victim of his own fame, but of a creator shaped by his time. Martin is a twentieth-century writer living under twenty-first-century dynamics: franchises, shared universes, global fandoms, and industrial content cycles. He built a world too large to fit on the page alone, yet he still believes it is on the page that his work ultimately justifies itself. The interview does not promise that The Winds of Winter will arrive soon. What it offers is something rarer: an artist’s awareness of the price of his own myth. The crown is heavy not because it is made only of gold, but because it is made of expectations, disputes, grief, time — and a question that follows him like a silent refrain: how do you finish, when everything around you conspires to keep the story from ever ending?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.