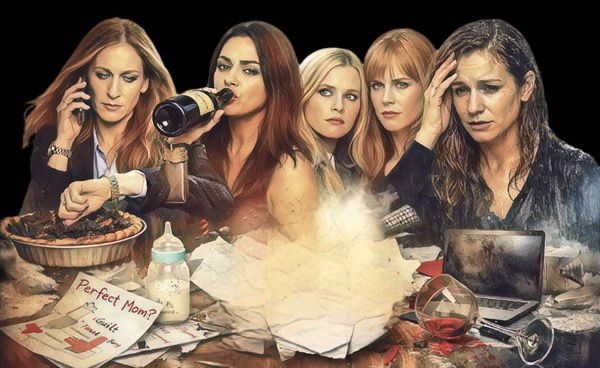

Even we, as women, resort to irony when talking about the “fix-everything” role that patriarchal society has piled onto female shoulders. Humor becomes a defense mechanism, a pressure valve, a usable language. But the truth is that this subject is far from a joke — even though comedy remains the most common way films and TV series attempt to address the problem.

The success of All Her Fault — and the many scenes in which female guilt is explicitly foregrounded — underscores exactly that. What is most disturbing about the series is not the mystery itself, that almost procedural engine of contemporary suspense, but the way it organizes, distributes, and multiplies guilt. Not guilt as a final revelation, but as atmosphere. As a permanent state. As an emotional language learned long before any facts are established.

All Her Fault understands something essential: women are taught to believe that control equals responsibility. If something slips out of alignment — a child, a marriage, a routine, an ordinary day — the failure must be theirs. It’s no coincidence that the narrative advances less through concrete clues than through emotional states. The real investigation isn’t police work; it’s internal. Each female character carries a private inventory of decisions that might have been different. And that inventory weighs more heavily on them than on the men around them. Men make mistakes. Women blame themselves.

That same mechanism appears, under a different mask, in I Don’t Know How She Does It. At first glance, it’s a light comedy about juggling work, motherhood, and marriage. But beneath the machinery of a “professional rom-com,” the film operates in exactly the same emotional territory: chronic female guilt. There’s no crime here — only something almost as socially unforgivable: failing to do everything with ease, a smile, and flawless efficiency.

The story’s origin helps explain this. The film adapts the 2002 novel by Allison Pearson, written from direct experience: a woman trying to balance career, children, and identity at a moment when the idea of the “woman who can have it all” had solidified — without any structural changes to support that “all.” Even the title carries the trap. I don’t know how she does it sounds like admiration, but functions as disguised pressure. If she can do it, why can’t you?

In the film version, starring Sarah Jessica Parker, the tone is softened, conciliatory, and almost hopeful. Guilt doesn’t explode; it’s managed. The store-bought cake passed off as homemade isn’t rebellion — it’s a coping mechanism. This isn’t about breaking the ideal, but surviving inside it without punishment. The protagonist doesn’t collapse because she fails; she collapses because she keeps functioning. And functioning becomes an obligation.

Where All Her Fault dramatizes collapse, I Don’t Know How She Does It normalizes exhaustion. Guilt becomes a joke — but a nervous one, instantly recognizable. We laugh because we see ourselves. Comedy works here as anesthesia, not as a cure.

That boundary between joke and drama becomes even clearer with Bad Moms. The film is born from a different energy. Its creators, Jon Lucas and Scott Moore, didn’t start from an abstract concept, but from direct observation of the women around them — wives, friends, mothers crushed by an impossible ideal. The initial question was blunt: When did motherhood become a competition?

Unlike I Don’t Know How She Does It, Bad Moms doesn’t try to organize guilt; it exposes it until it becomes absurd. The protagonist isn’t irresponsible or careless. She does everything right — and is still exhausted. The film’s transgression isn’t drinking, swearing, or abandoning duties for a few hours. The real transgression is admitting the model itself is unsustainable.

There’s a crucial point here: the critique isn’t aimed only at men or an abstract patriarchy, but at pressure among women. The “perfect moms” aren’t villains by accident. They embody internalized ideals — women who genuinely believe that control, surveillance, and demands are virtues. The laughter comes from uneasy recognition: many women see themselves both in the exhausted mother and in the enforcer.

This is where Big Little Lies becomes the connective tissue among these registers. It’s neither pure mystery nor outright comedy. It’s a psychological drama that understands guilt as social glue. The women in that community live surrounded by secrets, silences, and performances of happiness. Guilt isn’t only individual; it’s collective, shared, and normalized. Even as victims, they ask what they might have done differently.

Psychologically, all of these points point to the same mechanism. From an early age, women are taught to link worth to performance. They are “good” when they care, organize, anticipate, balance, and soften. When something fails, the mind doesn’t ask whether the task was impossible — it asks why she didn’t do better. Pressure rarely appears as overt violence. It shows up as constant vigilance, silent comparison, permanent self-monitoring.

The system is effective because it requires no visible aggressor. Guilt runs on its own. It activates in silence, in mirrors, in watching other women. And because of that, it spreads. Women reproduce expectations onto other women not out of cruelty, but out of survival within a model that only rewards those who appear to manage it all.

That’s why this guilt repeats itself. Why it crosses cultures, genres, and generations. In All Her Fault, it appears as psychological devastation. In I Don’t Know How She Does It, as manageable humor. In Bad Moms, as caricatured as rebellion. In Big Little Lies, as silent judgment. The setting changes; the internal script remains.

In the end, perhaps the distinction between joke and drama is merely aesthetic. The guilt is the same. The weight is the same. What changes is whether the narrative lets us laugh at it, sink into it — or, in the best cases, recognize it as a cultural construction rather than an individual failing.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.