Rome was dressed in black. But red was everywhere.

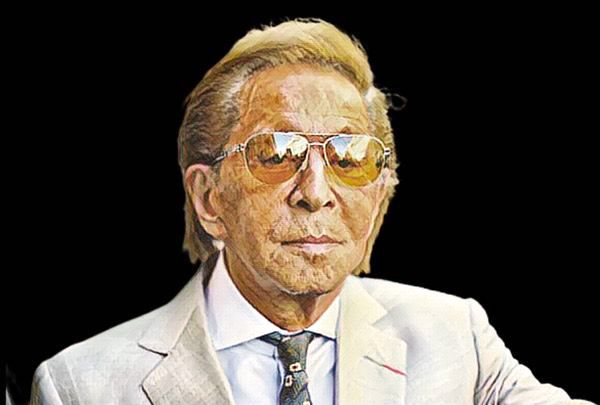

Inside the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels and the Martyrs, where the funeral of Valentino Garavani brought together designers, actresses, fashion editors and admirers, the farewell was not only to a man, but to an idea of beauty. Tom Ford, Donatella Versace, Anna Wintour, and Anne H,,athaway were among those present. Outside the church, fans wore red accessories, while some guests broke the mournin,g dress code with details in the colour that would become synonymous with the designer. Valentino red was not merely a tribute. It was language.

Valentino’s death at the age of 93, on January 19, 2026, crossed Hollywood as a symbolic mourning. For many actresses, he was not simply a creator, but someone who made them feel and look like the best version of themselves. The farewell in Rome was, at once, intimate and historic. A rite of passage for a designer who always understood that fashion is less about clothes and more about memory.

Even far from film sets and Hollywood front rows, Valentino defined for decades what cinema understood as glamour. On red carpets, where fashion often seeks impact, rupture,ure and spectacle, he chose permanence. His dresses were classic, almost simple at first glance, yet absolutely perfect. They did not compete with actresses or films. They amplified the moment.

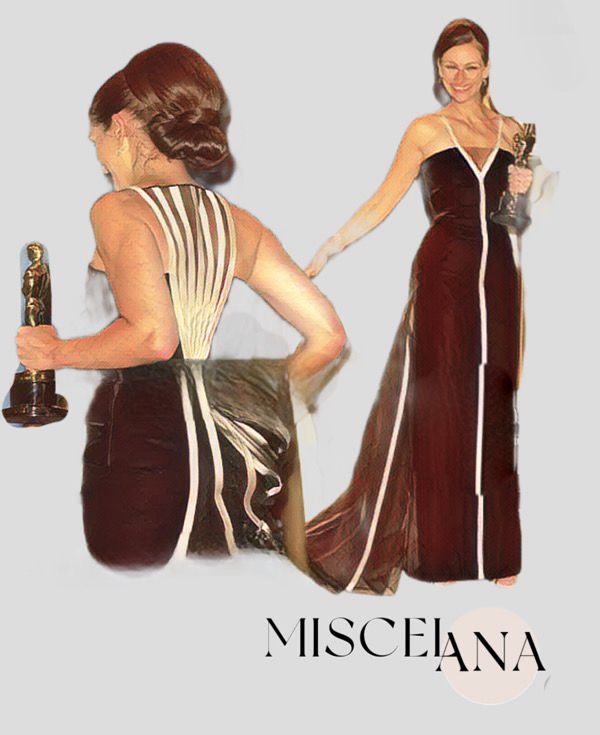

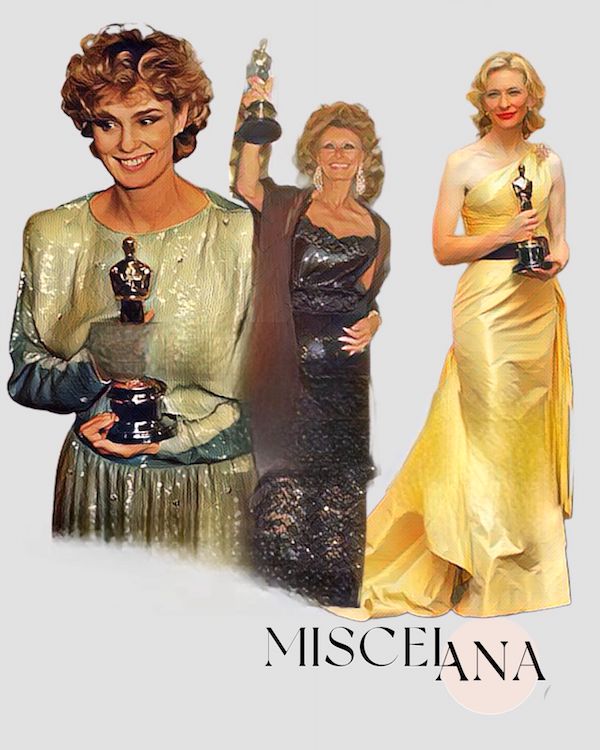

There was something almost ritualistic about Valentino’s relationship with the Oscars. In Hollywood, people used to say he was lucky. He dressed women who, minutes later, would become winners. Julia Roberts walked onto the stage in 2001 wearing a black-and-white archival Valentino gown when she won for Erin Brockovich. In 2005, Cate Blanchett received the Oscar in a pale yellow taffeta Valentino dress when she won for The Aviator. Before and after them, Halle Berry, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Lopez, Anne Hathaway, Sandra Bullock and Reese Witherspoon turned to his signature at decisive moments in their careers.

Valentino did not simply dress stars. He d,ressed narratives. His gowns seemed designed for the instant when a woman crosses a stage and becomes myth.

The creator who chose permanence

Born in 1932 in northern Italy, Valentino built his training between Paris and Rome, but it was in the Italian capital that he consolidated his own language. While fashion reinvented itself every decade, he chose continuity. The absolute red that would become his signature, the elongated silhouettes, the meticulous embroidery, the combination of delicacy and feminine power. Everything in his work seemed to resist time.

Alongside Giancarlo Giammetti, his creative and business partner, Valentino turned his maison into an aesthetic institution. What he offered Hollywood was not merely clothing, but a worldview. The belief that classical beauty could still be radical.

Valentino and cinema

Valentino was never a costume designer in the traditional sense, but he was present in cinema like few fashion creators. His creations did not function as ornament, but as language.

In Night Watch, he designed Elizabeth Taylor’s wardrobe, transforming elegant dresses into a symbolic contrast with the character’s psychological fragility. Luxury does not soften fear. It makes it more visible.

In The Taming of the Scoundrel, Ornella Muti appears as a strong, determined female figure, and Valentino’s costumes, especially a striking red jacket, become the visual axis of the narrative. Clothing ceases to be detail and becomes an assertion of power.

Decades later, his dialogue with auteur cinema intensified. In The Staggering Girl, directed by Luca Guadagnino, haute couture pieces from the maison appear as part of the film’s emotional architecture. Dresses, capes and coats translate memory, identity and the tension between past and present.

In contemporary mainstream cinema, the brand re, mains present. In Don’t Look Up, key characterswear Valentino as a contrast between formal elegance and the political absurdity of the narrative. In Priscilla, the maison’s dresses and suits help construct the atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s and the visual identity of a young woman trying to exist beside a myth.

But it was in the documentary Valentino: The Last Emperor that the designer became a character of himself. Directed by Matt Tyrnauer, the film follows the backstage of his career and reveals the conflict between the creator and the portrait made of him. Valentino resisted the documentary, rejected versions, demanded cuts, and feared exposure. What was at stake was not only public image, but the clash between perfection and vulnerability.

The film ultimately became the most honest portrait of a creator who always believed that beauty should be absolute and who, paradoxically, became more human when his cracks appeared.

Red as aesthetic inheritance

Long before becoming a symbol, red was a founding gesture. Valentino presented his first red dress in 1959. From that moment on, he decided there would be a red dress in every collection he produced.

The shade he developed, a scarlet with a subtle blue undertone, became more than a colour. It became language. A red capable of crossing skin tones, cultures, and eras. A sensitive, deep, human red.

Decades later, Valentino red remains one of the rare colours that carry author, memory and emotion at the same time. Few creators achieved something similar. Valentino did not leave only dresses. He left a colour as a cultural heritage.

His dresses still feel contemporary because they were never hostages to the present. Valentino understood before anyone else that glamour is not trend, but memory.

And as long as cinema continues to need images that survive time, there will always be something of Valentina or in Hollywood’s greatest moments. Even when he is no longer in the front row of the red carpet, but in the hardest place to occupy. Eternity.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.