There are families that belong to history. And some families belong to imagination. The Kennedys have always lived in the second realm, where politics, glamour, tragedy, and fiction blend until they become inseparable.

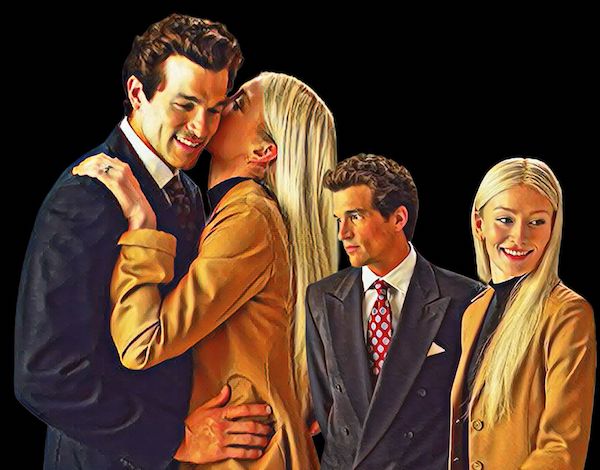

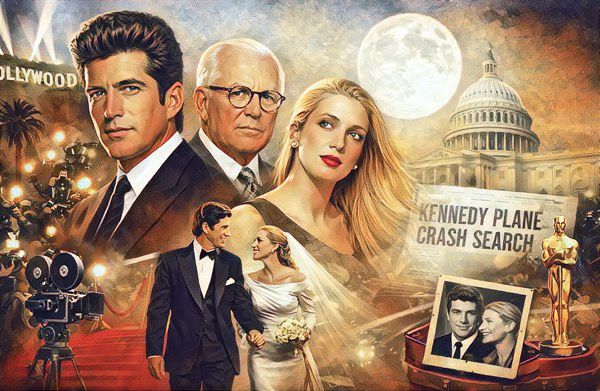

Decades after the assassinations that marked the clan, the scandals that eroded it from within, and the defeats that distanced it from power, the fascination remains. Perhaps it never diminished. The premiere of Love Story on FX/Hulu/Disney and the development of a Netflix series about the Kennedys, conceived in the mold of The Crown, are merely the latest signs of an obsession Hollywood has never abandoned.

The question, then, is not why the Kennedys have returned. They never left.

Hollywood has always had a particular relationship with dynasties. Cinema intuitively understands what politics sometimes tries to conceal: that power is, above all, a narrative. The Kennedys were perhaps the first modern political family to fully grasp this — and to stage it with cinematic perfection.

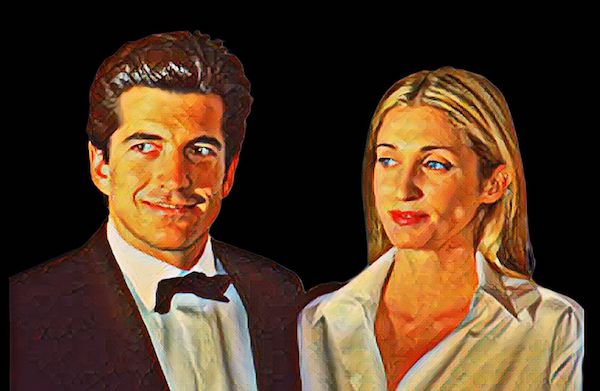

John F. Kennedy was not just a president. He was a character. Jacqueline Kennedy was not just a first lady. She was an image, an aesthetic, an idea of elegance that the entire twentieth century tried to imitate. Robert Kennedy, Ted Kennedy, their children, their grandchildren — all seemed to live under the logic of an ongoing saga, where each generation inherited not only privileges but also a prewritten script of greatness and ruin.

This combination is irresistible to the cultural industry: beauty, youth, ambition, idealism, scandal, and premature death. The Kennedys offer everything a great series needs. They are, at once, Camelot and Greek tragedy.

But there is something deeper behind this renewed interest. In times of political disillusionment, opaque leadership, and public figures without aura, the Kennedys represent nostalgia for a moment when power seemed to have style, purpose, and dramaturgy. Even if that image was, in part, constructed — or falsified — it remains seductive.

Love Story does not emerge by chance. By revisiting the romantic imagery associated with the Kennedy name, the series touches on a persistent fantasy: the idea that, at some point, politics and emotion, state and love, power and humanity were aligned. Netflix’s bet on a The Crown-style narrative reveals something else: the Kennedys are not just American history; they are global material, exportable, understandable anywhere in the world as a symbol of democratic aristocracy — a perfect paradox for streaming.

There is also the element of sin. The more one tries to crystallize the Kennedys as myth, the more irresistible it becomes to explore their fractures: extramarital affairs, ties to the mafia, family secrets, silent guilt, accumulated tragedies. Hollywood knows that there is no more powerful narrative than one in which brilliance and decay walk side by side.

In the end, the fascination with the Kennedys says less about them and more about us. About our need for heroes who seem larger than life, yet human enough to fail. About our desire to believe that power can be beautiful, that politics can be epic, that history can be told like a series — with charismatic protagonists, clear antagonists, and tragic endings.

The Kennedys keep returning because they were never just a family. They were — and still are — a collective fiction. And Hollywood, as always, knows how to recognize when a myth can still yield great stories.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.