There is something paradoxical about People We Meet on Vacation. The film is fragile as a cinematic work, predictable as a narrative, and timid as a romantic comedy. And yet, it worked. Not only did it work, but it became one of the most-watched titles on Netflix, reaching the global Top 10 and consolidating itself as a phenomenon among younger audiences.

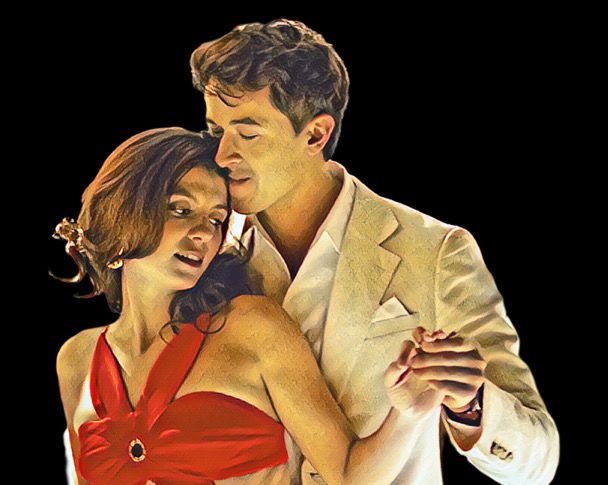

The explanation lies not in the film’s quality, but in the intelligence of its formula. People We Meet on Vacation is, essentially, a contemporary reimagining of When Harry Met Sally, with inverted roles and a sensibility adjusted to the spirit of the times. Here, Alex occupies the role of the neurotic, analytical man who rationalizes feelings. Poppy embodies the expansive, impulsive, and emotional energy that, in the 1989 classic, belonged to Harry. The dynamic is familiar, almost comforting, but rarely surprising.

The story follows Poppy and Alex, longtime friends who have turned annual trips into a ritual of intimacy. Over the years, they travel through cities, share confidences, and build a relationship that never quite defines itself as romance—until something breaks. The film returns to this past through fragmented memories, reconstructing the moments that led to their separation and the inevitable revelation of love. The structure alternates between present and past, but without major narrative risks. Everything is calculated to lead the viewer to the expected ending.

The film is based on the novel of the same name by Emily Henry, published in 2021, and quickly turned into a bestseller. Henry built her reputation by exploring affective relationships marked by irony, melancholy, and fear of intimacy, and her book precisely captures the sentimental imagination of a generation that loves cautiously and hesitates to name feelings. The adaptation preserves this atmosphere, but dilutes the emotional complexity of the text in favor of a more palatable and visually seductive narrative.

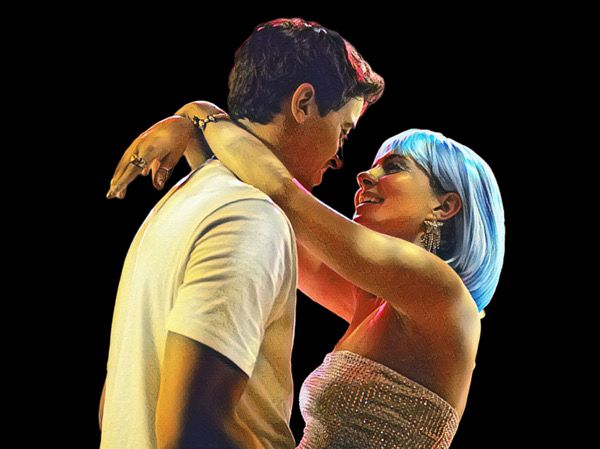

Tom Blyth and Emily Bader lead the cast with competent performances, but rarely memorable ones. Blyth builds Alex as a restrained, introspective character, almost excessively rational. Bader gives Poppy a restless, expansive energy, but one limited by a script that prefers likability to real conflict. The chemistry between them exists, but it never produces the kind of emotional tension that defines great romantic comedies. The supporting cast functions as a human backdrop, reinforcing the sense of displacement and nostalgia the film tries to construct, but without major highlights.

The greatest merit of People We Meet on Vacation is not artistic, but cultural. The film understands the audience it was made for. It speaks the language of a generation that prefers recognition to surprise, identification to complexity, comfort to rupture. There are no memorable dialogues, no scenes destined to endure for decades, as in When Harry Met Sally. What it offers instead is a succession of recognizable moments, calibrated to go viral on social media and generate emotional engagement.

That is why its success on Netflix is less a mystery than a symptom. People We Meet on Vacation is weak as a reinvention of the genre, but efficient as a product of its time. It does not reinvent the romantic comedy—it simply translates it for an audience that no longer expects love to be grandiose. And perhaps that is precisely why it reached the global Top 10: because it offers exactly what its audience wants to see.

In the end, the film behaves like a domesticated version of When Harry Met Sally. It replaces sharp intelligence with emotional comfort, verbal conflict with sentimental silence, and aesthetic ambition with algorithmic efficiency. It is not a great film, nor does it intend to be. It is merely a faithful portrait of an era in which love ceased to be epic and became manageable.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.