As Published in Bravo Magazine

I leave Tiradentes with the sense that Brazilian cinema is living through a paradoxical moment. Never before have we been so widely seen, discussed, and celebrated abroad, and at the same time, never has the gap between isolated success and the everyday reality of independent production been so evident. Here, this imbalance is neither ignored nor glossed over. It structures the conversation.

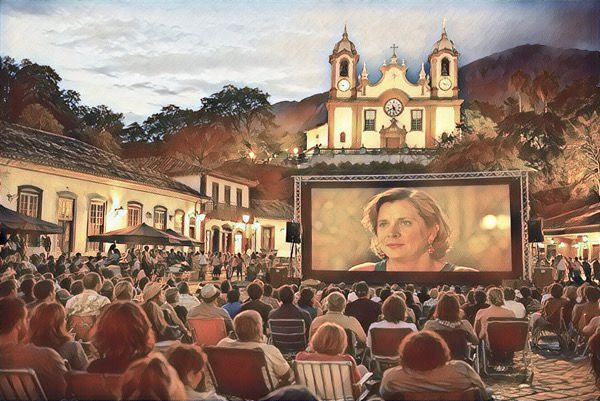

The numbers from the 29th Tiradentes Film Festival help measure the strength of the event. There were 137 Brazilian films in pre-release, from 23 states, more than 38,000 people circulated through the city over nine days, and more than R$10 million was injected into the local economy. Tiradentes is neither a small nor a self-absorbed festival. It is an event that mobilizes people, money, and ideas.

But data are never an endpoint. They are a starting point. What moved through theaters, debates, and corridors was a shared perception. The Oscar is a source of pride, yes, but it solves nothing on its own. Brazilian films that reached that stage are important, beloved, and legitimate, but they cannot represent independent cinema as a whole. They are exceptions within a system that remains fragile, unequal, and under pressure.

That is why Tiradentes keeps its discourse grounded. There is no atmosphere of euphoria or self-promotion. The festival continues to fulfill a less comfortable but more necessary role: that of a space where Brazilian cinema thinks itself structurally. A place to talk about public policy without evasions, circulation without illusions, and survival without romanticizing it.

The most immediate concern that ran through the festival and was formalized in the Tiradentes Charter is clear: the impact of streaming on the Brazilian audiovisual ecosystem. Not as an abstract enemy, but as a concrete force that concentrates resources, visibility, and decision-making power. The pressing question is no longer whether platforms are here to stay—that is already a given—but under what rules, with what obligations, and in service of which project of cinema.

In this context, Tiradentes reaffirms its historic function. While international awards celebrate the exceptional, the festival insists on the essential. The Brazilian cinema debated here does not live on peaks of recognition, but on consistent public policies, fair circulation, and sovereign imagination. It is not a comfortable or triumphalist discourse. It is a necessary one.

It is from this perspective that director Raquel Hallack speaks. More than an assessment of the current edition, her reflections point to the place the festival occupies today—not merely as a showcase, but as a space for formulation, listening, and the dispute of meaning. Below isan exclusive conversation with Bravo! magazine, in which Hallack expands on the ideas that shaped this edition and discusses the concrete challenges facing Brazilian cinema amid streaming and public policy debates.

BRAVO: We’re already talking a lot about the next edition, the 30th, but how—and if—the current one, the 29th, differed from previous editions?

Hallack: Look, we have a production format that includes training activities, screenings, reflection, and the dissemination of the best fruits emerging here at Tiradentes. The main difference is always the films. Each edition represents a theme under discussion—this year, Imaginative Sovereignty. To understand this curatorial cut, there were 137 titles from 23 Brazilian states, showcasing the plurality of content and the diversity of contemporary production. What’s always new is these films meeting their audiences.

BRAVO: And the public squares and theaters are always full, right? Everything is free. How is it to organize all of this? Is it easier 29 years later?

Hallack (smiling): No. Each edition is its own challenge, and we always start from scratch. Of course, over time, we acquire know-how in making the festival happen, but the funding model is based on incentive laws. We write the project, submit it to the Ministry, to federal and state incentive laws, seek sponsorship, and then arrive in Tiradentes, equipping the city with all the necessary infrastructure. There are three cinemas set up, plus all the technical equipment needed to support the breadth of programming offered to all ages. There are activities for children, young people, adults, and seniors. And it’s precisely this diversity that renews the challenge every year—putting cinema in dialogue with the edition’s theme, with literature, dance, visual arts, and the performing arts. Here, art is everywhere, and Brazilian film is the great protagonist.

BRAVO: What is the biggest challenge for a curator?

Hallack: Selecting 137 films out of more than 1,500 submissions. It’s about finding a representative cut for each edition that reflects this continental-sized Brazil. How can we bring, every year, a kind of X-ray, a cartography of the production being made by people entering cinema under very different conditions—where they come from, what kind of cinema they are making, what new narratives and aesthetics are emerging? This requires a curatorial team of ten professionals to arrive at the portrait we presented here.

BRAVO: What Brazil did the festival project in 2026? What Brazil are we seeing on screen?

Hallack: It’s Brazilian cinema made up of many Brazils. Many stories, many realities—films resulting from public grants, precarious productions, experimental films, and established works. This vast, plural production is what makes Tiradentes a space for exchange, knowledge, and business opportunities. Many productions and inspirations also begin here. This immense Brazil becomes present through the stories told by these films.

BRAVO: And the urgency—and priority—of regulating streaming?

Hallack: The bill has been debated in Congress for nine years. With the current administration, the debate intensified, and there was a unanimous decision among those who participated in the Tiradentes Forum: it is urgent and necessary that the regulation be voted on as soon as possible in the bill currently in the Senate. Even if it is not the ideal bill the sector envisioned, it is necessary, because every year this regulation is delayed, the sector loses more than one billion reais. Afterthe regulation, there is still a period before the law actually comes into force. The Tiradentes Forum hosted several discussions on this, making platform regulation one of its main thematic axes and the top priority for the sector.

BRAVO: How can Brazilian art situate itself within this battle of algorithms?

Hallack: I think that’s where the counterpoint to algorithms comes in: experience, living the festival environment. Here we are discussing all the possibilities involving audiovisual production—post-pandemic consumption shifts, algorithms, platforms, contemporary screens—while at the same time experiencing the darkened theater, being with family and friends, discussing the film you just watched, understanding the stories being told, and who is telling them. Developing a critical perspective on what is being shown. This combination of the modern, nostalgia, experience, and lived engagement has been transformative for those willing to immerse themselves in this audiovisual season.

*The reporter attended the 2026 Tiradentes Film Festival at the invitation of the event

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.