Since my adolescence, The Cure has been my favorite band. Not as a phase, but as a constant presence, one that has crossed decades while preserving the same feeling I had when I first heard A Forest and The Walk, that hard-to-name state somewhere between melancholy and emotional lucidity so characteristic of that period of life. That is why, when Robert Smith began publicly saying that The Twilight Sad was his favorite band, the gesture did not feel small. For those of us who grew up trusting Smith’s artistic instincts, listening becomes almost automatic, and unsurprisingly, I became a fan.

My point of entry came in 2015, when Smith re-recorded the single There’s a Girl in the Corner. It was a period of waiting for Cure fans, still longing for a new album, and the impact of that recording was immediate. Hearing the original version made the effect even stronger, because it sounded like a reissue of Joy Division displaced into the 2000s, not as an imitation, but as emotional continuity. The same dark pulse was there, the same sense of insistence, and that pushed me to look for more information. Because there was something beyond obvious reverence. There was affinity.

Origins: noise, poetry, and community

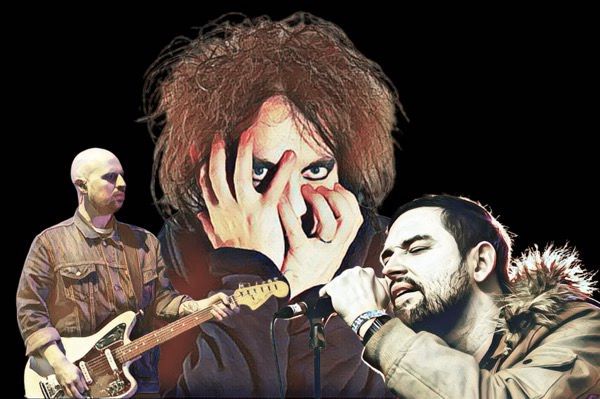

The heavy accent makes it clear from the start that The Twilight Sad comes from Scotland. Formed in 2003 in Kilsyth, the group has built a trajectory marked by emotional intensity, bold aesthetic shifts, and a constant refusal to settle. In 2025, after more than two decades of history, the band officially redefined itself as a duo, formed by its creators and main composers, James Graham, on vocals and lyrics, and Andy MacFarlane, on guitars, instrumentation, and music.

More than a musical project, The Twilight Sad has always functioned as a collective emotional archive, with songs that speak of small communities, silent traumas, unresolved losses, and feelings that rarely find direct language. Graham and MacFarlane met in high school, initially forming a cover band alongside drummer Mark Devine. Soon after, Craig Orzel joined as bassist, completing the original lineup. The band’s name comes from a line in the poem But I Was Looking at the Permanent Stars by Wilfred Owen, “Sleep mothered them; and left the twilight sad,” a choice that already pointed to the project’s melancholic and literary tone.

The earliest shows were radical noise experiments, with long jams, tapes, sound toys, and collages. The shift toward a more traditional structure led to the first original song, That Summer, at Home I Had Become the Invisible Boy, a title that already announced the band’s obsession with invisibility, memory, and displacement.

Sound and identity

From the beginning, the band has described its music as “folk with layers of noise,” a definition that helps explain the group’s central contrast: intimate lyrics anchored in dense walls of sound, shoegaze guitars, abrasive synthesizers, and live performances known for being physically overwhelming. Not by chance, their shows have been described as completely ear-splitting.

James Graham’s heavy Scottish accent functions as both a political and an aesthetic gesture, and The Twilight Sad has never sounded like a band willing to neutralize its own origins to reach some supposed universality. Listening to the group requires accepting that not everything will be immediately understood, but almost everything will be felt, and feeling, in this case, has nothing to do with comfort.

Robert Smith as a patron figure

The story of how Robert Smith came to The Twilight Sad is less mythical than one might expect, and precisely because of that, it says a great deal about him. There was no “discovery” in the classic sense, no label push or market strategy. Smith arrived at the band as an obsessive listener, attentive to contemporary British music, especially that which dialogued directly with post-punk without falling into caricature.

The first contact happened in the mid-2000s, when The Twilight Sad began to attract critical attention with their debut album Fourteen Autumns & Fifteen Winters, released in 2007. Smith heard the record through informal recommendation, something common in the independent circuit, and was immediately struck by the emotional climate, the use of accent, and the absence of any attempt to soften pain.

In interviews, Smith said he listened to the album repeatedly, describing it as one of the few contemporary records that genuinely affected him emotionally. What drew him in was not superficial similarity to The Cure, but the sense that this was a band treating difficult feelings with the same seriousness he had always defended, without irony and without distance.

From there, interest became a direct relationship. Smith began mentioning The Twilight Sad as his favorite band in interviews as early as the late 2000s, something that caught the attention of the press, and he started attending shows whenever possible, maintaining personal contact with Graham and MacFarlane. The most symbolic gesture came in 2015, when he decided to re-record There’s a Girl in the Corner, a track from the album Nobody Wants to Be Here and Nobody Wants to Leave. It was neither a commission nor a negotiated feature, but a personal choice. Smith has said he recorded the song because he felt the lyric and melody “asked” for his voice, as if there had always been a natural space for it there.

After that, the relationship deepened even further, with Smith inviting The Twilight Sad to open long Cure tours starting in 2016, including arena shows and historic dates, not as disposable opening acts, but as artistic partners, something extremely rare for an artist of his stature.

The interrupted tour and the weight of silence

With that history, when The Cure announced their South American tour in 2023, expectations were high, since The Twilight Sad was confirmed as the opening act, including dates announced at festivals such as Primavera Sound. Shortly before the start of the Latin American leg, however, the band announced they would have to withdraw from the tour. The statement was brief and cited personal and health issues, without further details.

This withdrawal needs to be understood within the emotional and structural context of The Twilight Sad. The band had come through intense years marked by constant lineup changes, grief over the death of close friends, illness within the family, long tours, pandemic-related postponements, and an extremely demanding relationship with their own material. By choosing to step away from the tour, the group did something few bands do when faced with a global spotlight: they prioritized their own emotional survival.

Out of that hiatus came the new album, It’s the Long Goodbye, which already has two released tracks and will be fully unveiled in March of 2026. The title carries an obvious weight, a long farewell, a process that does not end, a goodbye that stretches over time, and, precisely because of that, becomes part of life. James Graham has spoken openly in interviews about how the record also reflects saying goodbye to his mother, who died after many years living with dementia, often described as Alzheimer’s. That experience deeply shaped his personal life and his writing, marked by the idea of progressive loss and the anticipation of grief.

All of this is present behind the scenes of the first single, Waiting for the Phone Call, which marks the band’s return after six years without new studio albums. Robert Smith’s participation on guitar does not function as a novelty, but as a symbol, a direct dialogue between generations that share the same emotional territory. Graham described the song as a portrait of grief, love, and mental illness, three themes that run through the band’s entire body of work, now treated with less metaphor and greater frankness.

The second single, Designed to Lose, seems to condense the spirit of the album, with rare honesty in admitting that certain choices, paths, and even relationships are born with the seed of loss, not as stylized pessimism, but as acceptance and emotional maturity.

On It’s the Long Goodbye, The Twilight Sad writes directly about the inevitability of loss, not only of people, but of versions of oneself, of moments, and of places that do not return. The album offers no resolution and does not intend to, working instead with the idea that goodbyes rarely have clear contours.

Reducing the band to a duo does not impoverish the sound; quite the opposite, it makes everything more intimate, allowing the relationship between lyrics and music to become even more direct, almost confessional. Guest musicians appear in the credits, but the backbone of the album is the constant conversation between two creators who know each other deeply. Before the studio sessions came stripped-back performances, as if the band needed to face itself in the mirror before definitively recording those songs, and the result is an album that feels considered, intense, and never over-polished, emotional without being theatrical.

Perhaps that is why It’s the Long Goodbye feels like a record meant to be heard alone, yet shared as companionship. Because goodbye is a solitary experience, but recognizing it in someone else creates connection, belonging, and meaning. In the end, what unites The Cure, Joy Division, and The Twilight Sad is not aesthetics, but a refusal to turn pain into pose. These are bands that do not promise redemption, they simply remain in the dark with honesty, offering not answers, but presence.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.