Look, there is nothing more fascinating than Javier Bardem playing a villain. And the announcement that a new version of Cape Fear arrives on Apple TV Plus in June 2026 is worth celebrating, because if there is already a frightening character, whether on the pages of the original novel or in the two films made from it, that man is Max Cady. Even without seeing a single frame, I know it already. Bardem is going to crush it.

The new version of Cape Fear does not emerge as a traditional remake or as an automatic exercise in nostalgia, but rather as a kind of accumulation. From the book that inaugurated the nightmare, from the 1962 film that had to suggest what it could not show, and from the 1991 reinterpretation that decided to lay bare everything that had previously been contained. What Apple TV Plus proposes now is a Cape Fear that understands that, in 2026, the most effective terror is not immediate shock, but process, the slow erosion of safety, and the dangerous interval between threat and action.

Created, written, and run by Nick Antosca, the series starts from the same narrative engine that runs through all versions. A seemingly stable couple of attorneys, Anna and Tom Bowden, played by Amy Adams and Patrick Wilson, see their lives unravel when Max Cady, portrayed by Javier Bardem, is released from prison, determined to take revenge on those who put him behind bars. The difference lies less in the point of departure and more in the way the series chooses to look at this conflict.

Bardem takes on Max Cady as a character less interested in the final act than in the path leading to it. He is not merely a predator lying in wait, but someone who turns resentment into method, violence into discourse, and intimidation into a constant presence. There are echoes of Robert Mitchum’s insinuating Cady and Robert De Niro’s operatic one, but what dominates here is the idea of a man who understands the system, knows how to exploit it, and acts precisely where the law still cannot reach.

Casting Amy Adams as Anna Bowden reorganizes the emotional center of the story. If in earlier versions the lawyer was the absolute moral axis, the series shifts the focus to the one who senses the danger first and lives with it the longest. Anna is not merely a target or a witness, but a conscience. It is through her that Cape Fear comes closer to the spirit of the novel The Executioners, by John D. MacDonald, where horror never lies in the rape shown on screen, but in the constant threat, the unbearable anticipation, and the certainty that something terrible can happen while everything remains technically legal.

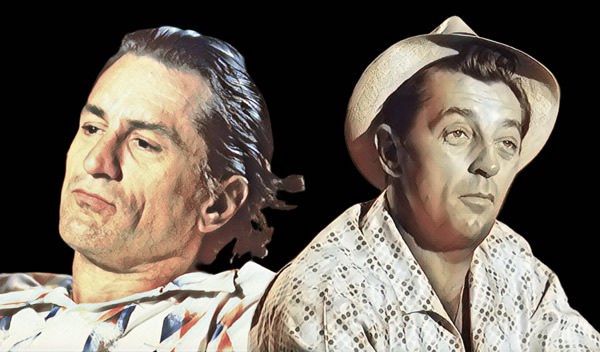

MacDonald’s book was direct for its time in making Cady’s past as a rapist explicit, yet it still chose not to turn sexual violence into spectacle. The terror resided in anticipation, in psychological wear, in the moral collapse of a father who realizes that the legal system fails precisely when it should protect the most. The 1962 film, directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Mitchum and Gregory Peck, translated this into silence and suggestion, limited by the Hays Code but also strengthened by it. Martin Scorsese’s 1991 version, on the other hand, broke with all restraint, brought the body to the center of the frame, and turned Cape Fear into an explicit nightmare about guilt, punishment, and sadism.

The Apple series seems fully aware of this trajectory and chooses another path. Instead of competing with the excess of the remake, it invests in what the serial format does best. Giving fear time. Following how the threat infiltrates everyday life, how symbolic violence precedes physical violence, and how justice reacts too late. In a world shaped by debates about abuse, power, and institutional responsibility, Cape Fear stops being merely the story of a vengeful ex-convict and becomes a commentary on the failure of the system to act preventively.

The production reinforces this historical weight. The series is developed by UCP in partnership with Amblin Television, with Steven Spielberg and Scorsese as executive producers, reuniting the duo behind the 1991 film. Adams also serves as an executive producer, as does Bardem, and the pilot is directed by Oscar nominee Morten Tyldum, signaling a visual and narrative ambition that goes beyond the conventional thriller. The supporting cast, which includes CCH Pounder, Jamie Hector, and Anna Baryshnikov, broadens the social field of the story and reinforces the idea that terror is not confined to the central family.

There is something circular and, at the same time, deeply current about this return. Spielberg and Scorsese reappear not to repeat a past impact, but to legitimize a reading that understands that today horror does not need to shout. It only needs to occupy the space between what is permitted and what is intolerable. In the end, the new Cape Fear seems less interested in asking what Max Cady is capable of doing and more in something far more unsettling. How long a society tolerates a threat before acting. It is a question posed in 1957, reformulated in 1962, radicalized in 1991, and one that, almost seventy years later, still has no answer.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.