Not every thriller wants to simply reveal who killed. Some want to show what happens when two people who know each other too well begin to fight over the same story, each armed with their own moral edit, their own selective memory, their own way of surviving what they have lived through. His & Hers, a Netflix limited series based on Alice Feeney’s novel of the same name, starts with a murder and moves toward something far more unsettling: the realization that intimacy and truth rarely coexist when the past returns demanding answers.

The story begins with Anna Andrews, a journalist and former TV news anchor living in seclusion in Atlanta, emotionally stalled, detached from her career and any sense of forward motion. When she overhears news of a murder in Dahlonega, the small Georgia town where she grew up, Anna is pulled back into a landscape shaped by memory, guilt, and identity. Professional instinct collides with personal history, and she decides to follow the case. The complication is that the detective officially assigned to the investigation is Jack Harper, her estranged husband, an experienced police officer who knows the town intimately and may know the woman who has returned without warning even better. The series unfolds exactly as its title suggests: his version and hers running in parallel, sometimes intersecting, often canceling each other out, always competing.

From the outset, His & Hers makes it clear that the crime is only the trigger. The real conflict lies in how these two people interpret the world and, more importantly, each other. Anna investigates with journalistic instinct, but also with open wounds. Jack investigates through police procedure, yet carries resentments, secrets, and losses that contaminate any claim to objectivity. Suspense arises not only from clues, but from the friction between two different ways of constructing truth.

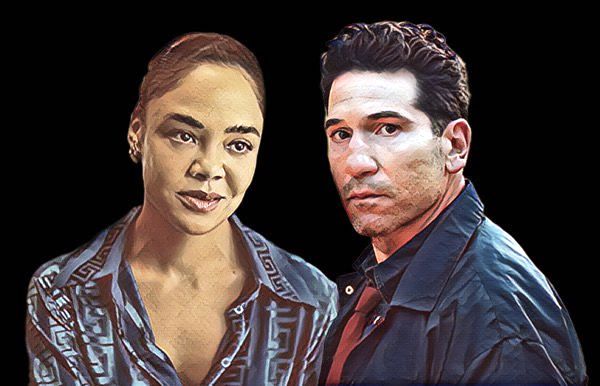

The cast sustains this tension with precision. Tessa Thompson plays Anna as someone constantly calibrating what she says, what she withholds, and what she truly believes, like a woman who learned early on that survival often depends on narrative control. Jon Bernthal shapes Jack as a man striving to be decent, yet whose choices reveal possessive impulses and a deep discomfort with anything he cannot contain. Around them, the series builds an entire community where everyone knows something, hides something, and participates, knowingly or not, in a collective lie.

Behind the scenes, the creative choices explain why the show refuses to behave like a conventional procedural. Led by William Oldroyd, the adaptation preserves the novel’s most important rule: there is no reliable narrator. Each episode repositions the viewer, invites allegiance, then quickly undermines it. The series does not seek comfort. It seeks doubt.

That strategy intensifies in the final episode, when His & Hers fully embraces excess. There are so many twists that the thriller edges toward melodrama, almost a classic soap opera of delayed revelations, hidden identities, and accumulated violence. And yet, curiously, it remains coherent with its original intent. Even when it flirts with implausibility, the series never abandons its emotional logic. Be aware of SPOILERS.

Lexy Jones’s transformation is the clearest example. The revelation that the charismatic news anchor is actually Catherine Kelly, the unpopular outsider hovering at the edges of Anna’s high school friend group, demands a generous suspension of disbelief. Lexy’s physical, social, and symbolic reinvention verges on the exaggerated. But the series leans into that excess because it needs the audience to accept the genre’s most obvious solution: the victim who returns as avenger, the woman who remakes herself in order to strike back. Everything points to her. The police point to her. Anna points to her. The audience does too.

Then comes the decisive shift. A final twist, withheld not from the characters but only from the viewer. Lexy was never the killer. The true murderer is Alice, Anna’s mother, responsible for the deaths of Rachel, Helen, and Zoe. This revelation is not a hollow shock. It reorganizes the entire narrative retroactively and displaces its moral center. The crime stops being about individual revenge and becomes something far more disturbing: maternal justice, a force that resists simple categories of good and evil.

Alice does not do it out of impulse, but conviction. She exploits her status as an older woman, underestimated, read as fragile or confused. She performs instability, simulates dementia, and makes herself invisible. The series is brutally precise in showing how ageism and misogyny function as social alibis. No one suspects Alice because no one imagines a mother capable of calculated violence. She succeeds precisely because she occupies a place society refuses to see as dangerous.

What drives Alice, however, is not rage alone. It is inherited trauma. Throughout the series, there are persistent hints of something terrible that happened on Anna’s sixteenth birthday. When the past finally surfaces, the truth is that sexual violence was inflicted on Anna, orchestrated and enabled by the girls she once called friends. The most unsettling detail is not only the assault itself, but the silence that followed. Anna never told anyone. Not her mother. Not her husband. Not even herself, fully.

Here lies one of the series’ most sophisticated moves. At the moment of “revelation,” Anna does not explicitly state that she was the victim. Her words remain ambiguous, almost displaced, as if she were speaking about someone else, as if she had escaped untouched. To the world, it appears she moved on. To her mother, watching the old tapes and finally understanding what happened, it becomes clear that Anna escaped nothing at all. She simply learned how to function despite the trauma.

That dissociation is what enrages Alice. Not only what was done to Anna, but also the fact that her daughter continued living without ever naming her own pain. Alice’s revenge is silent because it is born of a silent love, a desperate attempt to repair what was never spoken. By killing, she believes she is returning something to her daughter that was stolen: justice, control, voice.

The ending pushes this ambiguity to its limit. Anna learns the truth but does not expose it. The final look exchanged between mother and daughter is neither horror nor full approval. It is recognition. Alice did everything for Anna, including the unforgivable. And Anna understands.

The marriage to Jack survives, but only through omission. They reconcile, adopt Meg, build a new life, and expect another child. Everything appears resolved. It is not. Jack does not know the full truth. He does not know that his mother-in-law killed his sister. He does not know that the woman he has reunited with carries this secret. Anna chooses silence. The series closes by reaffirming its core thesis: in a story of his version and hers, someone is always lying.

It is rare to encounter a narrative that delivers such a clear ending while remaining so profoundly ambiguous. His & Hers leaves no doubt about what happened, yet opens every possible question about what it means. Unresolved trauma shapes not only the charactersbut the very structure of the story. The crime does not close the narrative. It crystallizes the silences that were always there.

In the end, His & Hers embraces its excess and almost turns it into virtue. It is a thriller that becomes melodrama, a melodrama anchored in real pain, and a story unafraid to suggest that truth, love, and justice rarely align. True to its premise, the series offers no moral comfort. It offers something far more unsettling: the certainty that when survival depends on the story we tell, the lie may be the only possible pact.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.