It may seem contradictory to celebrate Joni Mitchell’s art as legendary precisely because she did something that very few artists manage to sustain over an entire lifetime: she turned her own subjectivity into artistic language without softening it, without making it palatable, and without accepting the role she was expected to play. Her work does not stem from a desire to represent a generation or to offer neatly organized emotional answers, but from an insistence on thinking out loud through music, even when that meant losing audience, prestige,e or comfort. In today’s vocabulary, Joni was and has always been deeply authentic.

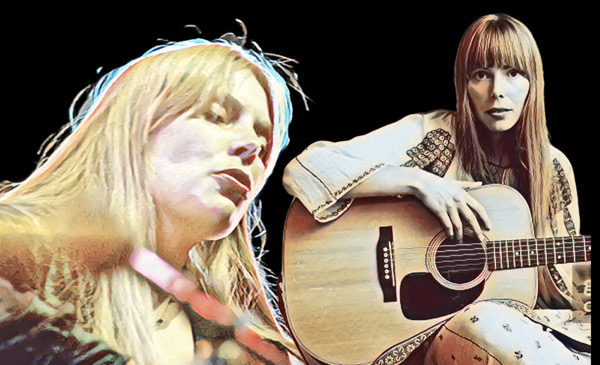

With her gentle voice, poetic lyrics, the visual signature of long hair, banjos, and almost no makeup, accompanied only by a guitar or a piano, Joni was one of the artists who rewrote the place of women in popular music worldwide. Before her, women sang emotions, but rarely controlled form, discourse, and point of view entirely. Joni composed, wrote, arranged, played, experimented with her own tunings, and spoke of desire, ambivalence, guilt, freedom, motherhood,d and abandonment without apology and without seeking absolution. Her presence was neither decorative nor conciliatory. It was authorial in the most radical sense of the word.

Considering that one of her greatest successes, Both Sides Now, has crossed decades and continues to be used in scenes of strong emotional impact,ct such as Love Actually, and the Oscar-winning CODA, telling Joni Mitchell’s story on film becomes a necessary gesture. Her trajectory escapes the models that still shape how pop culture narrates genius, success, ess and legacy, especially when women are involved. Joni was not just a celebrated singer or a talented songwriter welcomed by a generous system. She was an artist who built her work through conflict with that system, paying a high price for insisting on change, on risk, on refusing to stay where she was expected to remain.

Her importance lies not only in the impact of her songs but in how they redefined what could be said and felt within popular music. Joni emerged from the 1960s folk circuit, but quickly distanced herself from the idea of being a voice of a generation, rejecting the role of political standard-bearer or collective symbol. Instead, she wrote about desire, ambivalence, guilt, freedom, jealousy, motherhood, and loss with a frankness that does not seek easy empathy or narrative redemption. Her work does not organize emotions to make them acceptable. It exposes them as they are, contradictory and often uncomfortable.

That gesture reaches a decisive turning point with Blue, released in 1971. The album became a landmark not because it was confessional in the shallow sense the term later acquired, but because it shifted the center of popular song into female experience without filters, without idealization,n and without the need to explain itself. Blue is an album permeated by desire, love, and sadness, essence, and, more than fifty years later, it remains an unavoidable reference, repeatedly cited among the greatest albums ever recorded.

What makes Joni’s story even more relevant for cinema, however, is everything that came afterward. Rather than repeating the formula that made her famous, she chose risk. She moved toward jazz, altered harmonic structures, changed tunings, fragmented melodies, and challenged commercial and critical expectations. She was accused of being difficult, hermetic, and ungrateful to the audience that had embraced her. She lost space, was marginalized, and endured decades of delayed recognition. Today, that trajectory is celebrated as proof of artistic integrity. At the time, it was treated asa deviation. Telling this story now also means revisiting how the industry reacts to women who refuse to remain stable, recognizable, and comfortable.

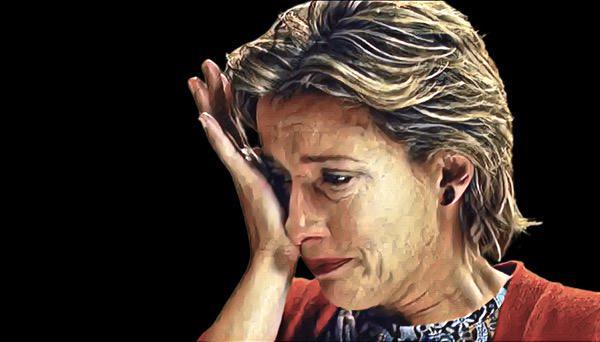

That is why a biopic about Joni Mitchell cannot be merely a chronological account of successes. Her life does not follow the classic arc of rise, fall,l and redemption. She does not offer a likable character or an uplifting journey. Perhaps that is precisely why the project currently in development has generated so much interest. According to recent confirmations, the film will be directed by Cameron Crowe, with consistent rumors that Meryl Streep will portray Joni in her later years.

Crowe is a particularly meaningful choice for this project, not only because of his historical relationship with music, but because his filmography has always shown an interest in creative processes, contradictions,s and gray areas. Almost Famous remains one of the rare films capable of understanding music not as myth, but as a formative experience marked by fascination, frustration, ego, and vulnerability. Crowe knows that world and, more importantly, knows how to listen to artists without reducing them to archetypes or caricatures.

The director himself has already made it clear that this will not be a traditional biopic. The script is not based on a biography written by third parties, but on Joni Mitchell’s own account of her life. The promise is of a film told through her prism, not through an external interpretation that organizes her trajectory into lessons or easy milestones. This is a fundamental choice. Joni has always resisted being explained. Her work is thought in motion. It makes sense that her story be told from within, with music functioning as both narrative and emotional axis.

At the center of this proposal is Meryl Streep, whose casting carries an evident symbolic weight. Streep is not merely an actress capable of imitation or surface reproduction. Her strength lies in building complex, contradictory characters sustained by emotional intelligence and silent presence. Playing Joni Mitchell requires less performative exuberance and more inner density, more listening than assertion. In that sense, the choice feels less obvious than profound.

For the younger version of the artist, names such as Anya Taylor-Joy and Amanda Seyfried have been mentioned, although nothing has been officially confirmed. This very uncertainty reinforces the idea of a film that may not be interested in dividing Joni’s life into didactic phases, but rather in capturing states of mind, inner rupture,s and creative displacements.

Telling Joni Mitchell’s story on film matters because it speaks to something still under dispute. Creative freedom within a system that punishes deviation. Artistic aging without complacency. The refusal to become a predictable brand. At a moment when Hollywood revisits icons of the past through domesticated nostalgia, Joni demands another kind of gaze, one that accepts complexity, silence,c,e and contradiction as narrative substance.

Perhaps, in the end, the importance of this film lies less in consecrating Joni Mitchell as a myth and more in recognizing something her work has always taught us. That the most enduring art is not the kind that comforts or explains, but the kind that remains in motion, open and unresolved. Joni never wanted to be resolved. If cinema can respect that, this will not be just a biopic. It will be a rare act of listening.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.