When The Walt Disney Company announced that Josh D’Amaro would become its new CEO on March 18, 2026, following a unanimous board vote, the news was initially framed as the conclusion of a long and finally resolved succession process. Reading it merely as a leadership change, however, misses its historical weight. D’Amaro’s appointment functions as a belated and explicit diagnosis of the crisis Disney endured throughout the 2020s and, by extension, of Hollywood’s broader structural collapse after betting everything on endless expansion, unrestrained streaming, and growth without a stable foundation.

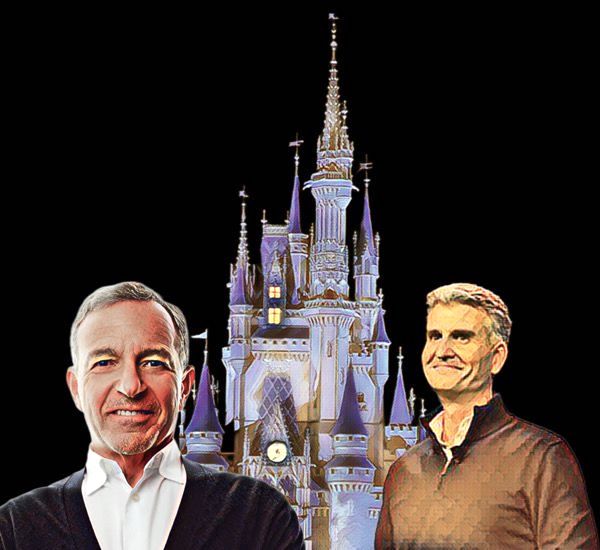

The story begins with Bob Iger’s original departure in 2020, presented at the time as a model transition after fifteen years of leadership that reshaped global entertainment through franchise consolidation and strategic acquisitions. The official narrative promised continuity and planning, but reality quickly exposed deep vulnerabilities. The pandemic shut down parks worldwide, removing Disney’s primary financial anchor, while streaming was accelerated as an emergency response, growing too fast, too expensive,y and without a clear long term identity or cost discipline.

Iger’s chosen successor was Bob Chapek, then head of parks, products, and experiences. The historical irony is unavoidable. Chapek also came from the parks, also embodied operational expertise, and appeared, on paper, to be a stabilizing choice. Instead, his tenure revealed the fragility of a succession executed at the worst possible moment. Chapek took over with parks closed, streaming artificially inflated by the pandemic,c and the company undergoing a reorganization that centralized financial power while weakening creative authority.

Disney produced more, spent more, and communicated less coherence. Investor confidence eroded, talent relationships deteriorated, and audiences began to feel the weight of content saturation stripped of cultural gravity. Chapek’s downfall was not simply personal. It marked the failure of a succession built on the assumption that operational control alone could replace symbolic leadership, especially when the company’s financial foundation had temporarily collapsed.

This context explains why Iger’s return in 2022 should be understood as an emergency intervention rather than a triumphant comeback. He returned to a company under pressure from activist investors, burdened by an unprofitable streaming model and soon confronted by historic writers’ and actors’ strikes that exposed fundamental tensions around labor, compensation,n and technology. His task was containment, not reinvention, restoring predictability and preparing a transition that would not repeat the earlier collapse.

Did it work? Partially. Disney regained stability, slowed production, recalibrated its strategy, and restored a sense of institutional control. But it was never meant to be permanent. Iger returned to close a cycle that had been abruptly broken, but time and step aside once the company could stand on its own again.

This is why Josh D’Amaro’s appointment represents a historical correction rather than a repetition of Chapek’s failure. The context has fundamentally changed. The parks are no longer vulnerable. They are dominant. In 2025, Disney’s parks, experiences, and products division generated roughly 35 to 36 billion dollars in revenue and accounted for more than half of the company’s operating profit. In the first fiscal quarter of 2026 alone, the parks brought in approximately 10 billion dollars, driven by higher per guest spending, premium offerings,s and resilient demand.

Those numbers settle the debate. If Disney was once defined by animation, then by films, then by television, then by global franchises such as Marvel and Star Wars, the 2020s made one truth unavoidable. It is Disney’s parks that now command the empire. Not by sentiment, but by structural necessity. The parks absorb creative risk, offset box office volatility, ty and give the company time when streaming burns cash or franchises lose momentum.

By choosing D’Amaro, Disney openly acknowledges that content no longer leads on its own. Films, series, and franchises are now components of an ecosystem whose center is physical, experiential, and financial. Stories must be expandable, recognizable, and capable of becoming space, riritual and memory, something no algorithm can replicate.

The creation of the Chief Creative Officer role and the appointment of Dana Walden further reinforce this reorganization. By clearly separating financial stewardship from creative guardianship, Disney seeks to avoid the Chapek era mistake, when financial centralization weakened creative coherence without solving the underlying structural problem. Walden becomes the protector of narrative identity, while D’Amaro ensures the system’s sustainability.

Bob Iger’s final exit by the end of 2026 closes this arc with a nearly pedagogical gesture. He leaves not because he failed, but because he represents an era that can no longer be replicated under the same conditions. His ultimate legacy may not be expansion, but the recognition that even empires must retreat, reorganize, and accept that the center of power has shifted.

In the 2020s, Disney learned the hard way that stories cannot survive on their own. They need ground beneath them. And in the Disney universe, that ground is still made of concrete, queues, ticketscastlese, and crowded parks.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.