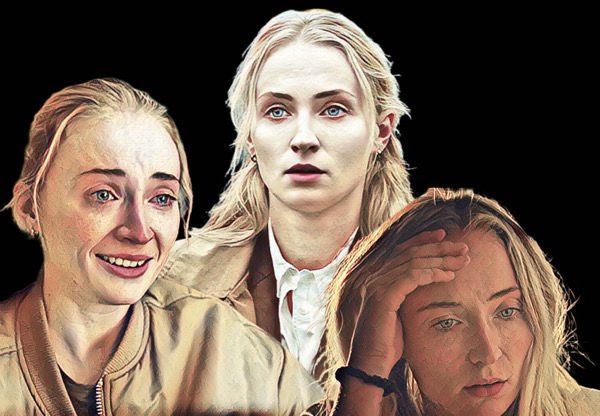

Sansa Stark, from Game of Thrones, used to say, rightly, that she was “slow to learn, but she did learn.” The role turned Sophie Turner into a star. The distance between Sansa and Zara Dunne, from the series Steal, is vast, but for the first time in many years, I found myself genuinely surprised by Sophie: at ease, versatile, and convincing. And if she were not quite so good here, the series itself might not work nearly as well.

Steal begins as a precise thriller and ends as something more unstable, more ambiguous,s and, for that very reason, more revealing. At first glance, it is a series about a heist of historic proportions, the armed invasion of a financial office, and the theft of billions of pounds from pension funds. But it quickly becomes clear that the narrative’s real interest is not the robbery itself, but what this extreme event draws out of ordinary people once the veneer of normalcy breaks.

Set within the antiseptic space of an investment management firm, Steal relocates the crime genre to an uncomfortably familiar territory. There is no glamour, no jewels, no cinematic vaults. What is at stake are abstract numbers that represent the future of thousands of anonymous workers. The heist does not invade a legendary bank, but an office like so many others. And that choice changes everything. Crime stops being a spectacular exception and becomes a mirror of a system that already operates, daily, through risk, betting, and inequality.

At the center of this collapse is Zara herself, who is, as mentioned, one of Turner’s most interesting post–Game of Thrones roles. Zara is neither constructed as a heroine nor as an exemplary victim. She appears disorganized, resentful, and emotionally adrift. A worker who feels stalled, undervalued, and trapped in a cycle of professional and familial frustration. Turner avoids any easy redemptive arc. Her Zara reacts like someone cornered. There is no choreographed bravery, only instinct.

This choice is not accidental. Turner has spoken openly about her interest in complicated, chaotic, potentially hard-to-love characters. Women who make mistakes, contradict themselves, who do not quite know who they are or where they are going. In Steal, that philosophy finds fertile ground. Zara does not “discover her strength” in an inspirational way. She is pushed into morally murky decisions by an accumulation of circumstances: wage inequality, a violent family past, and the constant feeling of having no value. What the series proposes is not a question of right or wrong, but of limits. How far can someone be pushed before they break?

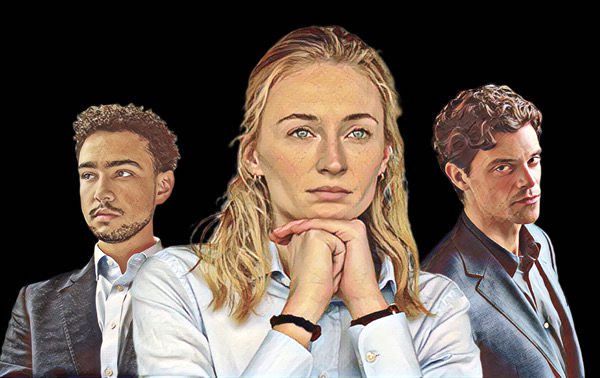

The dynamic with Luke, played by Archie Madekwe (Saltburn), reinforces this logic. While Zara hardens, he falls apart. Trauma does not produce universal responses. Some survive by adapting. Others simply break. The friendship between the two, built with an intimacy that spills beyond the screen, emotionally anchors the series even when the plot becomes more abstract.

Outside the besieged building, the investigation led by DCI Rhys, portrayed by Jacob Fortune-Lloyd (The Great), adds a clear thematic layer, though not always a dramatic one. His gambling addiction functions as a direct metaphor for the world Steal wants to explore: a world in which everything is a wager, in which a few gamble with the money of many and rarely lose. It is a powerful idea, even if the script does not always manage to translate it into narrative conflict of equal weight.

It is precisely here that Steal reveals both its greatest ambition and its main weakness. The series wants to talk about money as a moral force, about the obscene concentration of wealth, about the normalization of a system in which shielded executives accumulate bonuses while workers live on the edge. The diagnosis is accurate and relevant. The problem is that, after raising these questions, the narrative hesitates to take them to their ultimate consequences.

The first episode works as an exemplary thriller: lean, tense, almost self-contained. As the episodes progress, the series accumulates conspiracies, layers, and twists that do not always deepen what has already been established. But this is typical of British dramas: reversals that shift the course of the story. And here, it works.

Steal is compelling because it tries to go beyond genre, because it refuses to treat money as a neutral abstraction,n and because it trusts a protagonist who does not seek easy sympathy. And Sophie Turner stands out precisely for that reason, sustaining the ambiguity with intelligence, giving Zara a tense physicality, dry humor, and a vulnerability that never turns into self-pity.

The final arc offers no full catharsis, no clear redemption. Zara ends the series changed, more aware of her own capacity, but not unscathed. It is an ending consistent with a show that understands chaos not as spectacle, but as a contemporary condition. In a world where the system itself is already violent by nature, perhaps Steal’s greatest discomfort lies exactly here: realizing that the heist is merely the most visible symptom of something deeply wrong long before the guns came out.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.