As published on Bravo Magazine!

I am a Carioca who grew up away from the city. I was born in Rio, but only returned at 15, and perhaps because of that, I still consider myself a kind of eternal tourist in my own home. No matter how much time passes, I am still struck by the landscape, by the light slicing across the sea, by the perfect curve of the shoreline. For my foreign friends, walking through Copacabana or Ipanema feels almost like an initiation ritual, an experience that seems to step out of a living postcard. And there is something even more powerful when Copacabana stops being scenery and becomes a stage. In that moment, the beach takes on an almost mythological dimension, because what is at stake is not merely a concert, but the feeling that we are witnessing a chapter of the city’s cultural history being written before our eyes.

This monumental vocation was born on New Year’s Eve, long before any structured international megashow project existed. For decades, the turn of the year served as the great laboratory of the beach as a mass arena, and the leading figures were always essentially national. The concert was part of a collective celebration of popular identity, of the Carioca tradition that blends fireworks, white clothing, the sea, and music.

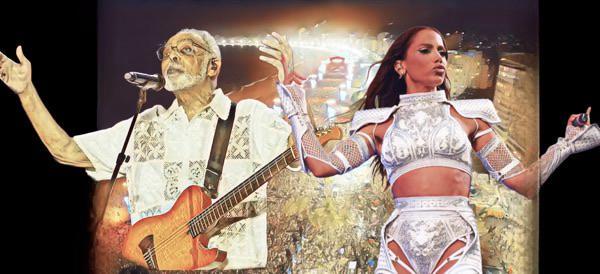

In 1994, when Rod Stewart performed before an estimated audience of between 3 and 4 million people, the record entered the Guinness Book and definitively established Copacabana as the largest open-air arena on the planet. Yet the phenomenon neither began nor ended there. Brazilian artists had already mobilized impressive crowds along the shoreline, and would continue to do so in the decades that followed. Jorge Ben Jor, Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, and Ivete Sangalo led New Year’s celebrations that traditionally gathered between 2 and 3 million people, numbers that make most international festivals seem almost intimate by comparison.

At the turn of 2025, for example, the Rio New Year’s Eve celebration brought together around 2.6 million people along Copacabana and Leme beaches alone. On the main stage, Caetano Veloso shared the spotlight with Maria Bethânia, while Ivete Sangalo led central moments of the night. At the turn of 2026, the pattern continued, with Gilberto Gil opening the evening alongside Ney Matogrosso, João Gomes sharing the stage with IZA, Alok commanding the midnight countdown with a drone spectacle, and Belo and Alcione reinforcing the presence of samba and pagode.

These events belong to a deeply rooted popular tradition in which the concert is part of a civic and collective celebration, rather than a deliberate strategy of international positioning. The distinction becomes clearer when we observe the second phase of this history, which begins to take shape outside the New Year’s Eve context.

In 2006, The Rolling Stones gathered around 1.5 million people for a free concert that was not tied to the turn of the year. The operation involved hundreds of tons of equipment, thousands of professionals, and an urban machine that transformed the beach into an autonomous spectacle. It was no longer merely a traditional celebration, but a demonstration of logistical strength and global reach.

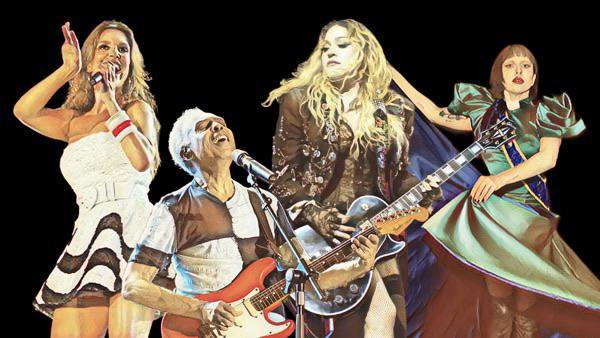

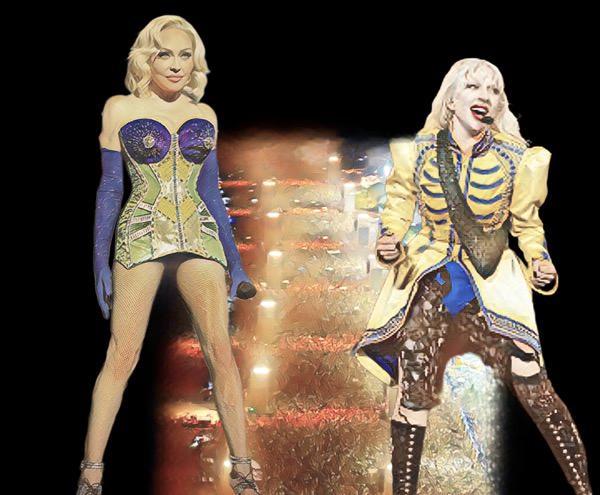

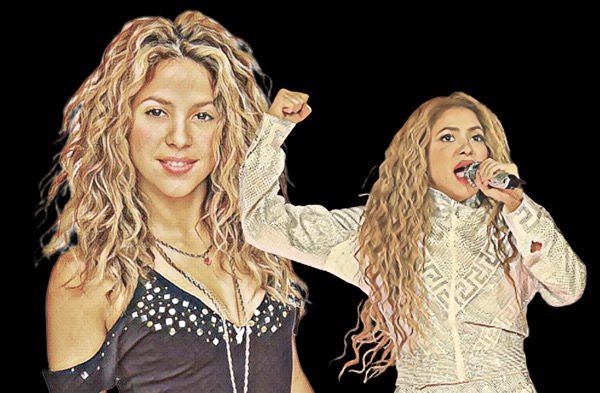

This movement has recently been consolidated with the Todo Mundo no Rio project, which deliberately transforms the beach into an instrument of soft power. In 2024, Madonna closed her Celebration tour before approximately 1.6 million people, with an estimated economic impact of over 300 million reais. The following year, Lady Gaga drew around 2.5 million fans to a free concert independent of New Year’s Eve, solidifying Copacabana as a global showcase for the closing acts of historic tours. In 2026, it will be Shakira’s turn.

Here, the concert ceases to be merely a celebration and becomes an urban strategy, structured cultural policy, and the construction of the city’s international brand. The scale remains monumental, but the meaning shifts.

Over the course of three decades, Copacabana has established a pattern that is extraordinarily rare in the world, combining an iconic landscape, free access, and crowds ranging from 1 to 4 million people, along with economic impacts that can surpass hundreds of millions of reais. These operations involve thousands of security agents, complex urban closures, stages rising up to 30 meters high, and broadcasts reaching international audiences.

It is within this context that Shakira steps in. She does not arrive merely to sing on the beach, but to occupy a space already layered with memory, tradition, and strategy. Copacabana amplifies everything it touches, and every artist who passes through ultimately becomes woven into Rio’s urban narrative.

Between New Year’s Eve as a popular ritual and Todo Mundo no Rio as a global strategic project, the beach has built something that transcends entertainment. It has built a narrative about itself. And when millions gather before the sea to sing in unison, what is reaffirmed is not only that night’s repertoire, but the very idea of Rio as a permanent spectacle, a city that lives from image, but also from encounter.

Perhaps that is why each new name announced carries the same silent question: will it be legendary? In Copacabana, it almost always is.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.