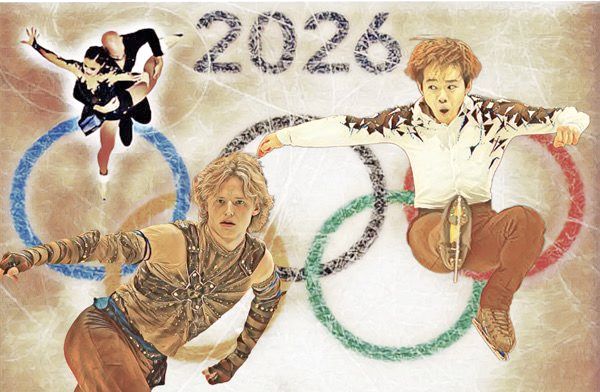

With all the fanfare surrounding Ilia Malinin at Milano Cortina 2026, an old question resurfaced with near indignation. Is it allowed? How is it allowed? And why wasn’t it before? The backflip, the popular backward somersault on ice, reappeared at the Olympic Games fifty years after its debut and immediate ban. And its story reveals less about acrobatics and more about power, memory, and who gets to challenge the rules without paying for it.

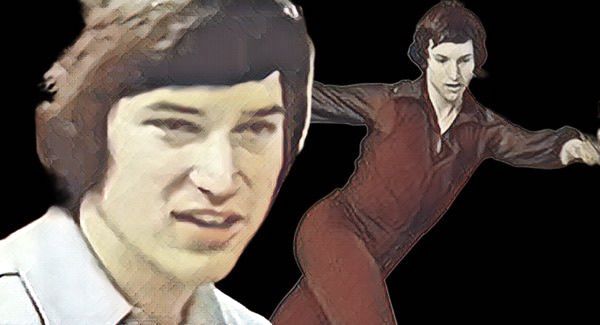

American skater Terry Kubicka was the one who “invented” the Olympic backflip, in the institutional sense of the word. At Innsbruck 1976, he executed the move in official competition. Kubicka was not an eccentric seeking notoriety. He was the 1974 World Junior Champion, a U.S. Junior National Champion, and one of the leading names on the American team that season. He finished seventh in Innsbruck. He did not win a medal, but he entered history.

The reaction was immediate. In 1977, the International Skating Union banned the move. Officially, for safety reasons. The argument centered on the loss of visual reference during the rotation and the potential risk of severe falls on the head or neck. There had been no specific accident in figure skating to justify the decision. But the broader sporting climate was increasingly sensitive to extreme risk. A few years later, in 1980, Soviet gymnast Elena Mukhina suffered a devastating cervical injury while training a high-risk element. Although Mukhina’s case was not directly related to skating, it crystallized a global debate about how far athletes should be pushed beyond physical limits. The atmosphere in elite sport had become one of growing caution.

There was also an aesthetic dimension. The backflip seemed too acrobatic for a sport that still viewed itself as an extension of classical ballet. Figure skating valued continuity, elegance, and codified landings on a single blade. The somersault disrupted that narrative.

Kubicka retired shortly after, became an orthopedic surgeon in the United States, and built a life far from the spotlight. His name remained attached to the first gesture, but not to the symbolic battle the move would later represent.

Five decades later, in 2024, the ISU removed the explicit ban. That allowed Malinin to execute the backflip at Milano Cortina 2026 in the team event. First with two feet. Then, in the free skate that secured gold for the United States, with one. The crowd erupted. Novak Djokovic threw his hands to his head in the stands. The move carries no specific scoring bonus, but it no longer results in a deduction. What was once an infraction has become a climax.

Social media, inevitably, was quick to resurrect the story of the last athlete who dared to perform it in Olympic competition: the French skater Surya Bonaly.

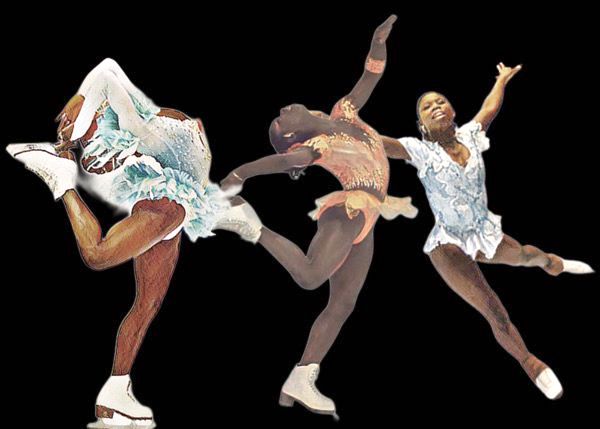

At Nagano 1998, Bonaly ended her Olympic performance with a one-footed backflip, fully aware of the penalty. In that moment, the gesture ceased to be merely technical and became symbolic.

Bonaly was a five-time European champion, nine-time French national champion, and three-time World silver medalist. She was one of the first women to land a quadruple toe loop in competition. She competed three times for Olympic gold. In the 1990s, figure skating’s television golden age, she was raw athletic power in an era that rewarded the choreographed delicacy of the so-called “ice princess.”

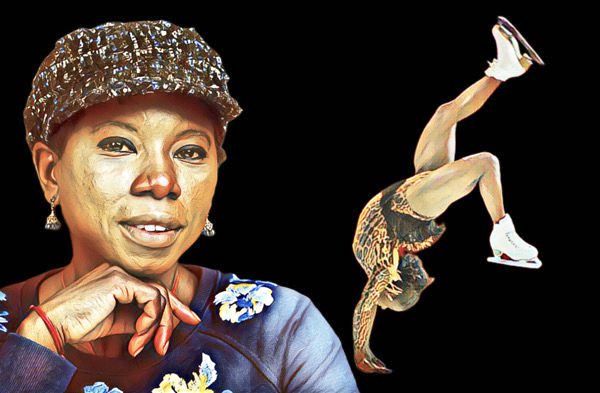

Adopted by a white French couple, with biological roots in Réunion Island and the Ivory Coast, Bonaly was too different in a sport that was too codified — and that remains largely white to this day. Her style, influenced by gymnastics, was considered unorthodox. She has always been cautious when speaking about racism, but artistic judging is fertile ground for implicit bias. For years, she was labeled a rebel.

Before the 1998 backflip, she had already made headlines in 1994, at the World Championships in Chiba, Japan, when she refused to wear the silver medal she had just received.

That night, Bonaly delivered a nearly clean program. She executed her jumps with power, maintained great technical difficulty, and left the ice convinced she had done enough to win gold. The title, however, went to Yuka Sato. The margin under the old 6.0 system was minimal. But the system was deeply subjective. There was no mathematical transparency as there is today. Judging combined technical execution with “artistic impression,” a category inherently open to personal interpretation.

When the result was announced, Bonaly stepped onto the podium, received the silver medal, and removed it from her neck in front of the audience. It was a silent yet explosive gesture. Years later, she acknowledged it was unsportsmanlike. She avoids calling it injustice. She does not directly accuse racism. Still, the context is impossible to ignore. The episode became emblematic of her challenge not only to a result, but to a judging system that rewarded a very specific ideal of femininity and elegance.

As an explosive athletic force, applying gymnastic technique to ice, she did not fully fit that mold. Today, under the post-2004 numerical scoring system, many specialists argue that Bonaly would have benefited from a code that objectively rewards technical difficulty. In 1994, under 6.0, judging was taste disguised as numbers.

And that is what she contested, even without words.

At the next Olympics, in 1998 in Nagano, she included the backflip in her program and was again penalized. By then, she was already out of medal contention. The deduction was 0.2 points per judge under the 6.0 system. It affected both technical marks and overall placement because rankings were ordinal. The backflip did not cost her a medal. She finished 10th. But with that conscious, symbolic gesture, she ended her Olympic career with a moment that entered history.

After Nagano, she turned professional, toured the world during skating’s commercial golden era, and has lived in the United States for over two decades. She now works as a coach and has spoken about becoming a motivational speaker. Recently, she underwent treatment for breast cancer while caring for her mother, who is also battling cancer. During that period, her Las Vegas home was burglarized, and her medals were stolen — European, national, junior, and awards once handed to her by French officials. They were not merely metal. They were memories.

There is something profoundly symbolic in the fact that the move that cost her points now lifts crowds under applause and legality. The American inaugurated it. The young prodigy revived it. But it was the Frenchwoman who turned it into History and was punished for challenging rules that were not yet ready for her.

The backflip has returned to the Olympics fifty years later. But what truly returned is an old question. On ice, as in culture, it is never simply about whether something is allowed. It is about who is allowed — and when the world decides it is finally ready for the audacity it once punished.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.