If Milano Cortina 2026 feels like the height of an era in which costumes are stealing the spotlight, it is because there was a long road to get here. Figure skating has never been only about technique, but for a long time it dressed as if it were. The ice was a territory of disciplined elegance. Costumes followed protocol. Creativity existed, but it was contained.

In the early twentieth century, when skating still carried a strong influence from European ballet, women competed in long dresses with closed sleeves and heavy fabrics. Decorum was the priority. The sport was associated with aristocracy and social refinement. Freedom of movement was limited not only by technique but by clothing.

In the 1940s and 1950s, skirts shortened, fabrics became lighter, and silhouettes adapted better to jumps and spins. Still, the visual ideal remained classical. Nothing was meant to distract from what was understood as the purity of line. Men wore dark trousers and discreet shirts. Neutrality was the unspoken rule.

Sparkle began to gain ground in the 1970s as television expanded the sport’s reach. Closer cameras demanded visual impact. Crystals and embellishments became more common. Even so, the overall aesthetic remained relatively homogeneous. Romantic femininity for women. Athletic restraint for men.

The 1990s brought heightened public drama. The rivalry between Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan exposed something uncomfortable. Harding, often competing in handmade or less polished costumes, was judged not only on her technique but on her appearance. Clothing became a marker of class and belonging. Media narratives made clear that image and scoring were never entirely separate.

Until the early 2000s, however, formal rules still limited creativity. Women were required to wear skirts in singles and pairs competitions. The expectation that costumes preserve a traditional standard was institutional.

The major inflection point came after the judging scandal at the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics. In 2004, the ISU introduced a new scoring system. Program Components began to formally assess interpretation, composition, and presentation. Costumes did not receive direct points, but they began to influence how those components were perceived. Presentation became codified. Clothing entered the equation, even if indirectly.

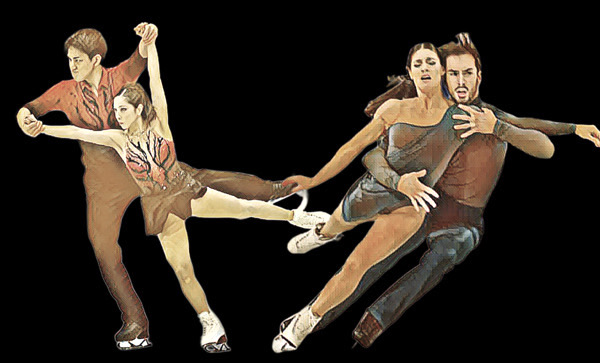

That same year, the requirement for women to wear skirts was removed in singles and pairs. Unitards, trousers, and alternative silhouettes became permissible. This technical shift opened space for new visual languages. In 2022, further updates expanded flexibility in ice dance as well. Creativity, once constrained by explicit regulation, gained institutional ground.

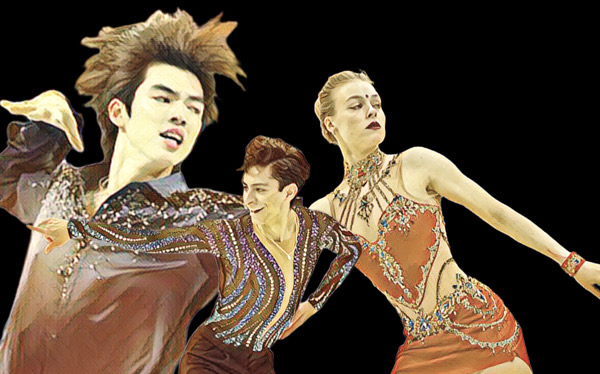

At the same time, fashion’s relationship with skating intensified. Vera Wang, a former skater herself, became a symbol of that bridge between haute couture and the ice. She dressed Nancy Kerrigan at the 1992 Olympics, collaborated extensively with Michelle Kwan, and designed for Evan Lysacek and Nathan Chen. With Wang, the costume became more than functional. It carried fashion vocabulary.

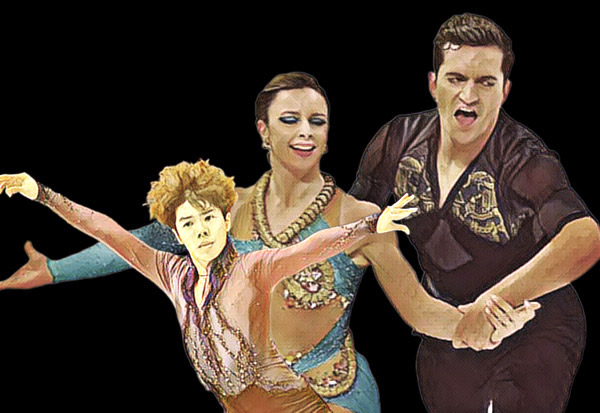

Other names professionalized the field. Mathieu Caron elevated the visual sophistication of ice dance through close collaboration with elite athletes. Lisa McKinnon built a strong presence in the American circuit, dressing skaters such as Alysa Liu and Amber Glenn while incorporating pop and couture references. Ito Satomi redefined modern men’s skating aesthetics through her work with Yuzuru Hanyu, blending Japanese tradition with contemporary drama and influencing an entire generation.

Creativity became not merely allowed but expected. Costumes evolved into strategic tools of differentiation. In a sport decided by fractions of a point, a clear visual identity can help judges and audiences understand the story being told. Clothing does not replace technique, but it shapes perception.

The rules still draw boundaries. Attire must be modest, dignified, and appropriate for athletic competition. It cannot resemble a literal theatrical costume. Removable props are prohibited. Any piece that falls onto the ice results in a deduction. Designers learned to sew with redundancy, reinforce closures, and distribute crystals carefully to manage weight. A costume may contain thousands of stones, but it must remain light enough not to interfere with rotation and lift.

What Milano Cortina 2026 reveals is the culmination of this evolution. The costume is no longer simply an elegant uniform. It is symbolic armor. It is an extension of choreography. It is identity in motion.

When Alysa Liu steps onto the ice in a grunge-inflected look adapted to regulation, she carries decades of transformation. When Ilia Malinin performs in the precise constructions of Ito Satomi, he embodies a moment in which masculinity in skating moved beyond timidity or caricature into intentional design. When ice dance embraces cinematic storytelling through flamenco, architecture, or surrealist inspiration, it reflects a process that began when creativity stopped being tolerated and became language.

Costumes steal the spotlight today because they no longer ask permission. And because the ice has finally acknowledged that aesthetics, too, are performance.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.