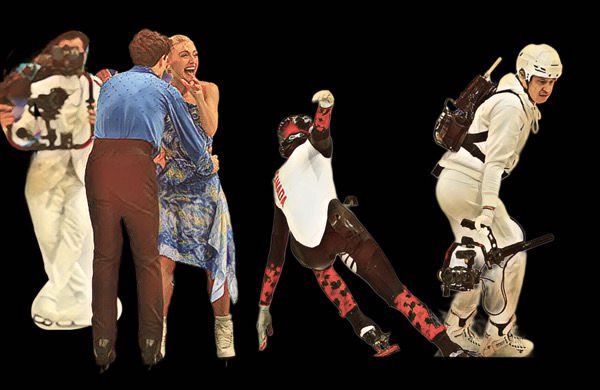

As Milano Cortina 2026 approaches its end, it is not only the athletes who are obsessively refining every detail. Broadcast productions are doing the same, aiming to deliver something that now feels essential: the sensation of being inside the rink. If today we are moved and able to perceive with almost intimate clarity every nuance of figure skating, it is because the visual language of sports coverage has evolved to the point of placing the camera on the ice itself, gliding alongside the athlete. This is neither a metaphor nor an editing trick. In many performances, the person filming is literally skating too, following the choreography in real time and transforming the viewer into an almost physical presence within the spectacle.

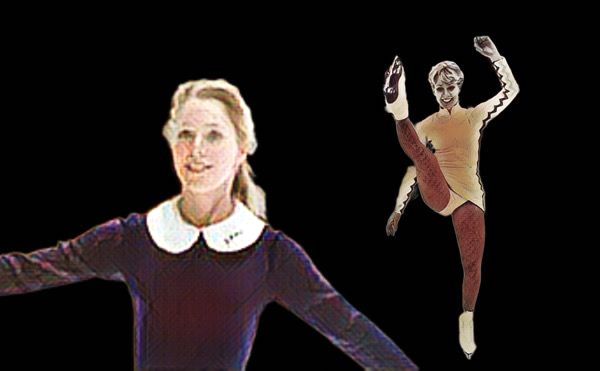

For decades, however, figure skating was conceived as something to be contemplated from a distance, closer to a ballet viewed from the audience than to an immersive experience. Cameras remained in the stands, along the rink boards, or suspended above the ice, recording the choreography as an elegant, controlled, deliberately distant pattern. Viewers watched as one observes a painting in motion, fully aware of the beauty yet separated from it by an invisible barrier. Skating seemed to belong to a world of its own, silent and untouchable, where the body wrote on ice while the camera merely documented, never participated.

When we think of Ice Castles, the film that helped shape popular imagination around figure skating, this logic is still evident. Although it includes shots taken on the ice, they do not produce the immersive sensation that now feels natural. These were cautious approximations, often achieved with heavy equipment, improvised tracks, or operators being guided by skaters. The camera visited the ice but did not converse with it. There was no sense of breathing alongside the athlete, of sharing the speed, the risk, or the vertigo of a jump. The result was beautiful yet external, as if the visual narrative maintained a ceremonial distance from the moving body.

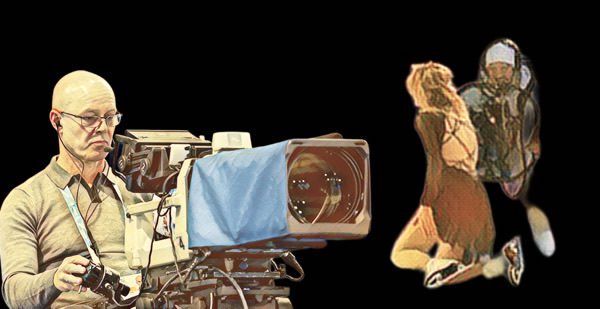

The shift began when technology stopped imposing such rigid limits on movement. The miniaturization of digital cinema cameras, the development of increasingly sophisticated stabilizers, and above all, reliable wireless transmission allowed the camera to become truly mobile without sacrificing image quality or stability. In productions tied to major sporting events and television broadcasts, operators began strapping on skates and following athletes during rehearsals and performances, sending live images to crews positioned safely outside the rink. Directors and technicians could monitor everything in real time and even control focus and zoom remotely while the operator concentrated solely on framing and trajectory.

A significant milestone in this transformation was the introduction of specialized live capture systems operating directly from the ice, such as the so-called “Ice Cam,” handled by experienced figure skaters equipped with body-mounted stabilization rigs. In these setups, a broadcast-quality camera transmits the signal off the ice while another operator controls the lens remotely, creating an invisible collaboration between the person skating and the one ensuring technical precision. Extensive rehearsals are required to synchronize movements, anticipate paths, and avoid interfering with the performance. The operator’s background as a skater is crucial because only someone who understands the mechanics of the sport can intuitively predict accelerations, spins, and jumps that demand clear space.

Before these innovations, even when cameras entered the rink, the methods were far more rudimentary. Operators sometimes walked on the ice wearing spiked shoes to prevent slipping or used heavy Steadicam systems that restricted fluid motion. Oval tracks around the rink, remote heads mounted on dollies, and crane systems attempted to simulate proximity without actually sharing the skaters’ space. They produced close images but still felt external, unable to replicate the organic sense of movement that defines skating.

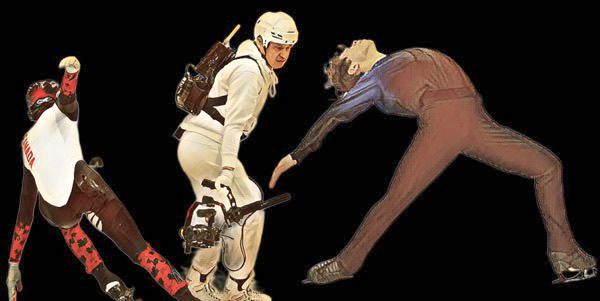

Stepping onto the ice with professional equipment requires a skill set that goes well beyond traditional cinematography. Operators must master advanced skating techniques, including high-speed travel, abrupt directional changes, and above all, the ability to skate backward with absolute stability while maintaining precise framing. At the same time, they carry stabilized rigs that distribute weight and absorb vibrations transmitted through the blades. In high-level broadcasts, these systems incorporate electronic gimbals, monitors, transmitters, and additional batteries, turning the operator into a complex and delicate mobile platform.

The greatest challenge, however, is not purely technical but choreographic. Figure skating is fast and unpredictable, with sudden accelerations, spins that compress visual space, and jumps requiring safety zones. The operator must know the music, memorize the sequence of elements, and anticipate trajectories in order not to invade critical areas or disrupt the athlete’s concentration. Each movement is calculated as part of a parallel dance that viewers rarely notice, yet upon which the fluidity of the images depends. A mistimed step can lead not only to a lost shot but to dangerous collisions.

Lighting and the physical nature of ice introduce further complications. The white surface reflects light irregularly, creating intense contrasts and unexpected shadows, while shimmering costumes can alter exposure from one moment to the next. The operator must constantly adjust angles to avoid reflections that obscure details or distort depth perception. All of this unfolds in continuous motion, without the possibility of interruption.

The emotional impact of this transformation is profound. Contemporary broadcasts bring viewers closer to physical effort, micro-expressions, and the tension preceding each jump, creating a sense of presence that once did not exist. We no longer see only the finished choreography but the bodily process that sustains it, the breath, the impact of landing, the fleeting instability before graceful recovery. Skating ceases to be a distant pattern and becomes an almost tactile shared experience.

If in the past the ice functioned as a symbolic boundary between performer and audience, today it has become a space traversed by the camera and, by extension, by the viewer’s gaze. This evolution is not merely technological but sensory and narrative. By learning to skate, the camera has altered the very nature of the spectacle, transforming a ballet observed from afar into an immersive experience that seems to unfold within reach. What was once contemplation has become presence, and perhaps this is the most significant change of all, because it is no longer simply about seeing better but about feeling more intensely what happens on the ice.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.