To understand why John Hughes’s films shaped an entire generation, you had to live through adolescence in the 1980s, when his stories transformed everyday conflicts into pop mythology. Many of those films have aged in ways that remain tied to the spirit of their time, but one endured with a vitality that is almost disconcerting precisely because it seemed the least ambitious of them all: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Four decades after its release, it remains not only a teen classic but a timeless portrait of youth, anxiety, and the desire to stop time for one perfect day. Ferris Bueller did not become legendary over the years. He entered the world that way.

Forty years after its release, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is not merely an 1980s classic. It is a film whose meaning has shifted without changing a single frame. In 1986, it felt like an impossible adolescent fantasy, a radiant comedy about a brilliant teenager who outwits the system to experience a perfect day in Chicago. In 2026, John Hughes’s film sounds less like escapism and more like a diagnosis. The exhaustion with rigid institutions, the refusal to perform productivity at all costs, and the pursuit of meaningful experiences instead of accumulated achievements have become a generational language. Generation Z does not need Ferris Bueller to teach them how to skip school. They were born already tired of what school represents.

The enduring success of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off explains why the film is still screened, analyzed, and quoted forty years later. At 40, Ferris Bueller remains relevant because he speaks about freedom, privilege, anxiety, and friendship with a lightness that conceals deep melancholy. It is not simply a teen comedy. It is an emotional portrait of someone who realizes too early that adulthood will not be gentle.

Behind the scenes: a film written at the speed of impulse

John Hughes wrote the screenplay in just a few days, during a period in which he seemed to capture American adolescence with almost supernatural precision. The film was conceived as a love letter to Chicago, and this is evident in how the city functions not merely as a setting but as an accomplice. The museum, the stadium, the skyscraper, the improvised parade. Everything seems to conspire in favor of that day.

The famous Ferrari was not a real Ferrari. They were replicas based on the 250 GT California model, used to preserve authentic cars and to allow the controlled destruction of the version that crashes through the garage. The museum scene was not fully choreographed in the script. Hughes allowed the actors to explore the space, which explains the almost contemplative atmosphere that contrasts with the chaotic energy of the rest of the film.

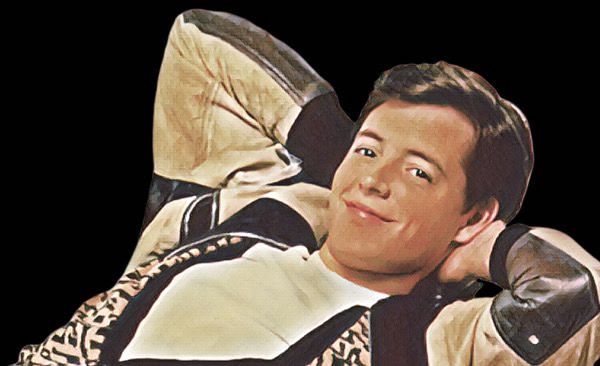

Matthew Broderick constructed Ferris as a conspiratorial narrator, someone who not only breaks the fourth wall but transforms it into an emotional bridge. This choice helped redefine the tone of mainstream comedy, anticipating the intimacy with audiences that now feels entirely natural.

Box office and immediate impact

With a modest budget, the film grossed tens of millions of dollars and became one of the decade’s biggest youth hits. More important than theatrical revenue was its continuous circulation on VHS, television, and later streaming, which allowed each new generation to discover it as if it were contemporary.

Ferris Bueller became a cultural symbol, an archetype of the charmingly irresponsible, invincible teenager. The line about life moving fast became an existential slogan. The parade sequence turned into one of the most recognizable scenes in popular cinema history.

Cameron, the true emotional protagonist

Over time, critical readings shifted. Many viewers began to see the film as Cameron Frye’s story rather than Ferris’s. The emotional breakdown in front of the pointillist painting, the oppressive relationship with the unseen father, the panic attack disguised as hypochondria. Cameron represents anxiety before anxiety became a common word.

This change mirrors a broader cultural transformation. The carefree genius friend is no longer aspirational. The paralyzed, fearful young man feels painfully familiar.

Where the actors are today

Matthew Broderick built a solid career across theater, film, and television, including major Broadway successes and significant dramatic roles. He never repudiated Ferris Bueller, but he never wanted to be defined by him either. Over the decades, he has repeatedly said he does not enjoy being called Ferris on the street, perhaps because the character represents a youth frozen in time while the actor moved forward. Today, he is recognized both for his stage work and for his personal life alongside Sarah Jessica Parker.

Alan Ruck had a quieter film career but returned to prominence with the series Succession, playing Connor Roy. It was a symbolic comeback, since Connor is also a character emotionally vulnerable, displaced, and slightly out of sync with the world around him. The connection to Cameron is unavoidable.

Mia Sara stepped away from Hollywood in the 1990s to focus on her personal life and family, returning only occasionally to selected projects. Her Sloane remains one of the most elegant and quietly self-assured portrayals of the idealized girlfriend in teen cinema.

Jeffrey Jones, who played Principal Rooney, saw his career severely damaged by later legal troubles. The character, already cartoonish in the film, came to carry an uncomfortable weight offscreen.

Jennifer Grey, Ferris’s resentful sister Jeanie, soon became a romantic icon with Dirty Dancing. Years later, she spoke openly about the surgery that changed her face and affected her career, a case frequently cited in discussions about identity and celebrity.

Charlie Sheen appears in a brief but memorable early role as the delinquent teenager at the police station who shares a scene with Jeanie. Built largely on improvised dialogue and quiet tension, the sequence became one of the film’s most unexpectedly iconic moments. Sheen appears disheveled and defiant, gradually revealing a surprisingly sensitive side as he talks to Jeanie about family pressure and rebellion. The scene functions as a counterpoint to Ferris’s sunny charm, introducing a darker note of reality. Decades later, Sheen’s turbulent public life adds an almost unintended layer of irony to that encounter, as if the film captured a raw, not yet domesticated version of the actor who would later become one of Hollywood’s most controversial figures.

“Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

Ferris Bueller

The friendship between Broderick and Alan Ruck

The chemistry between Ferris and Cameron was not created by script alone. Broderick and Ruck developed a genuine friendship before filming, a connection rooted in theater and marked by improvisation and trust. That bond is visible in the dynamic between the characters, which oscillates between admiration, dependence, and subtle rivalry. The film works because Ferris seems to truly believe he is rescuing his friend, while Cameron slowly realizes he must rescue himself.

Choosing Sloane

Mia Sara was cast because she conveyed emotional maturity without losing a youthful aura. Sloane is not merely a love interest. She is an anchor. Her presence legitimizes the day off as something more than childish mischief. There is a serenity in her character that contrasts with Ferris’s performative energy.

Lines and scenes that became part of culture

The parade set to Twist and Shout, the fake Abe Froman at the upscale restaurant, the baseball game, the frantic race home. These sequences have outgrown the film itself and now function as independent cultural references.

The line about life moving fast continues to be quoted in speeches, self-help books, and motivational posts, often without attribution. It is a rare case of dialogue that evolved into a cultural proverb.

What feels problematic today

Ferris Bueller lies compulsively, hacks school systems, manipulates adults, and faces no real consequences. In a contemporary context, this can be interpreted as white male privilege operating without friction. Principal Rooney’s caricature is also viewed with less sympathy, especially since the film invites audiences to laugh at an adult who, from another perspective, is simply trying to do his job.

Still, the film has not been canceled or rejected. It has been reinterpreted. Ferris has shifted from an unquestioned hero to an ambiguous figure.

The forgotten series and the musical

In 1990, NBC launched a sitcom based on the concept. Without the original cast and without Hughes’s tone, it failed quickly and is now mostly a historical curiosity, especially considering that a young, little-known Jennifer Aniston had hoped it would make her a star.

The subversion that became normal

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect is how the film’s central gesture no longer feels transgressive. Skipping school to protect mental health, prioritizing experiences over academic performance, and questioning institutional authority. These ideas have become part of mainstream discourse about well-being.

Generation Z does not see Ferris as an extraordinary rebel. They see someone who simply did what was necessary. Subversion has turned into self-preservation. Hedonism has turned into improvised therapy. The perfect day is no longer a fantasy but a survival strategy.

Why Ferris Bueller still matters at 40

Ferris Bueller at 40 remains a classic because it captures something universal and timeless. The desire to interrupt the automatic flow of life and experience the present intensely. The fear of growing up. The sense that adulthood is a closed system no one truly wants to enter.

The film not only teaches how to skip school. It teaches how to look around before it is too late. That may be why it still resonates so powerfully. Not because it offers answers, but because it recognizes a restlessness that crosses generations.

Forty years later, the question is no longer whether Ferris Bueller could exist today. The question is whether we are still capable of living a day like that without guilt, without productivity, without justification. The real fantasy is not escaping school. It is escaping the feeling that we must always be doing something useful.

And as Ferris says, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” In just 24 hours, he offered us an emotional repertoire capable of accompanying an entire lifetime.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.