Even amid recurring controversies over age, ethnicity, and fidelity to the novel’s letter, Jacob Elordi takes a significant step in his career by adding Heathcliff to his gallery of characters. For those who follow him on television in Euphoria or saw him shine on the big screen as Elvis Presley and Frankenstein, the mysterious gypsy who emerged from the pages and imagination of Emily Brontë is not merely another period role. Heathcliff is, in fact, a challenge comparable to Hamlet. Not by superficial analogy, but because both occupy the same symbolic place in the history of acting: that of the character who tests the boundary between technique, risk, and emotional exposure.

To understand why Hamlet and Heathcliff became this “double summit” of performance, one must return to the stories they carry and to the way those stories place the actor in a permanent state of instability.

Hamlet, created by William Shakespeare, is the tragedy of a young prince called to act in a morally decayed world. After his father’s death, Hamlet discovers that the king was murdered by his own brother, now married to his mother and seated on the throne of Denmark. The plot, on the surface, is simple: avenge the father. What Shakespeare constructs, however, is the portrait of a man incapable of turning awareness into action without destroying himself. Hamlet thinks too much, feels too much, perceives too much. Every possible gesture carries ethical, political, and existential implications that paralyze him. The story advances less through external events than through the character’s internal erosion, as he observes himself, accuses himself, and continually tests his own limits.

Heathcliff, in Wuthering Heights, is born from another wound. An orphan, a foreigner, and socially displaced, he is taken in by the Earnshaw family and grows up viscerally bound to Catherine. The narrative follows this absolute and impossible love, crossed by class differences, humiliation, and resentment. When Catherine chooses a socially acceptable marriage, Heathcliff transforms pain into a project of revenge. He does not hesitate, doubt, or reflect as Hamlet does. He acts, but acts from an emotional core so radical that everything around him becomes contaminated. The story moves not toward redemption but toward the repetition of trauma, passing that hatred forward as inheritance.

Here lies the first deep point of contact between the two characters. Hamlet and Heathcliff are figures shaped by an inaugural loss. Both have identities fractured by an event they cannot fully process. One loses his father and his trust in the world. The other loses love and the possibility of belonging. From that moment on, both live in a state of excess. In Hamlet’s case, an excess of consciousness. In Heathcliff, an excess of emotion. For the actor, this means sustaining characters who never rest, never stabilize, and never offer a secure center of interpretation.

Another essential similarity is that both resist simple explanations. Hamlet is not merely indecisive, just as Heathcliff is not merely cruel. They are characters constructed to frustrate direct moral readings. Hamlet can be seen as a coward or as the only lucid figure in a corrupt world. Heathcliff can be viewed as a victim or a villain. The text does not choose for us. This structural ambiguity is what turns both roles into permanent challenges for great actors, because any attempt to “solve” the character diminishes the experience.

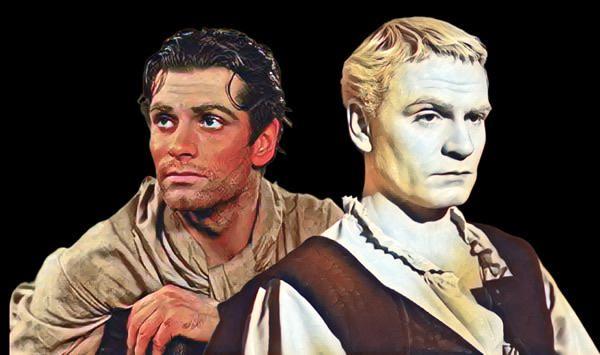

The tradition of viewing Hamlet and Heathcliff as twin roles of the high repertoire began to consolidate in the twentieth century, particularly with Laurence Olivier. Olivier was not the first to play them, but he crystallized the idea that these characters require a rare combination of formal rigor and internal disorder. By portraying Heathcliff on film in 1939 and Hamlet on stage and screen, he demonstrated that both demand the same kind of courage: restraint to intensify. His performances rejected easy outbursts and relied instead on accumulated tension, on the silence that threatens to break. Critics of the time sensed something new there. These were not simply great characters; they were roles that revealed the actor’s own method.

From Olivier onward, the notion that confronting Hamlet or Heathcliff meant passing through a rite of artistic maturity spread widely. It is no coincidence that figures such as Richard Burton and Ralph Fiennes returned to both characters at key moments in their careers. Burton brought to each a nearly destructive verbal and physical energy, drawing them toward fury. Fiennes, decades later, explored the claustrophobic and bodily dimension, emphasizing how profoundly these men are prisoners of themselves. Even the most debated case, that of Timothy Dalton, reinforces the logic of the tradition: actors drawn to Heathcliff tend to orbit Hamlet, as if one role inevitably summons the other.

At the deepest level, Hamlet and Heathcliff share something fundamental to the history of acting: both relocate the conflict of the story from the world into the actor’s body. The plot matters, but it is the internal state that drives everything. These are characters who do not ask for charisma, but for presence. They do not ask for empathy, but for sustained intensity. And they do not tolerate vanity.

This is why Jacob Elordi’s entry into this territory matters. Regardless of the controversies, taking on Heathcliff is not a gesture of comfort but of risk. It means accepting participation in a lineage that begins to take shape with Olivier and continues with actors who understood that certain roles do not exist to confirm talent, but to challenge it. Hamlet and Heathcliff do not crown those who portray them. They expose them. And perhaps that is precisely why, more than a century later, they remain the definitive test for great actors.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.