When it was first announced, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms seemed like a smaller project within the Game of Thrones universe. No dragons ruling the skies, no wars capable of destroying entire cities, and no palace intrigues deciding the fate of the world in a single episode. Yet it is precisely this reduced scale that proves to be its greatest strength. The series not only works, but it fills an essential narrative gap between House of the Dragon and Game of Thrones by showing the brutal everyday reality of those who live under the power of the great houses.

If House of the Dragon exposes how dynasties destroyed themselves from within, and Game of Thrones presents the collapse of that system, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms shows who actually pays the price for those struggles. It is the Andor of Westeros in the most precise sense of the comparison. Just as the Star Wars series revealed life under an oppressive empire through ordinary people, Knight shifts the focus to landless knights, orphans, mercenaries, peasants, and bastards struggling to survive at the margins of power. There is no romanticism in this world. There is dust, hunger, arbitrary violence, and a fragile dignity constantly under threat.

This perspective creates a powerful connection to the rest of the saga. Dunk and Egg travel through a realm that still appears stable but already carries the seeds of the chaos that will devastate Westeros decades later. The series works as a quiet study of cause and consequence. It does not compete with Game of Thrones or House of the Dragon; it explains them. It shows how the Blackfyre rebellions continue to shape politics, how the idea of honor was already a dangerous rarity, and how the feudal system produces unlikely heroes and inevitable tragedies.

The adaptation demonstrates remarkable respect for the tone of George R. R. Martin’s novellas. Instead of inflating the story with unnecessary battles or artificial intrigue, the production embraces intimacy. There is room for silence, for observation, and for the gradual construction of human bonds. The heart of the series is the relationship between Dunk and Egg, developed with a delicacy rarely seen in contemporary television, where shock and speed usually dominate.

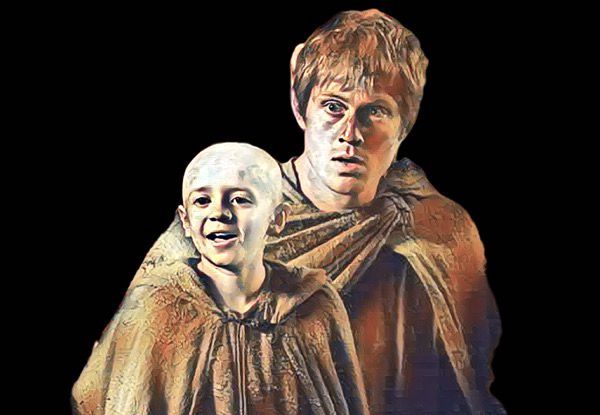

The casting is simply perfect. Peter Claffey delivers a Ser Duncan the Tall who captures the character’s essence with striking naturalism. His Dunk is physically imposing yet emotionally transparent, almost defenseless against the world’s cruelty. He does not seek heroism or glory. He acts out of moral instinct, as if he does not know how to exist otherwise. That purity makes him both admirable and vulnerable.

Dexter Sol Ansell, as Egg, is equally impressive. He builds a boy who is intelligent, proud, and profoundly lonely, avoiding any caricature of the disguised prince. His Egg already carries the weight of the king he will one day become, but also the fragility of a child stripped of any chance at a normal life. The chemistry between the two actors is immediate and convincing. They do not feel like newly introduced characters but like a pair that has always belonged to this world.

The supporting cast reinforces that sense of authenticity. Even brief appearances carry emotional weight and implied backstories. Every face feels as though it truly belongs to Westeros, strengthening the sense of reality. This is not a grand fantasy stage; it is a lived-in place.

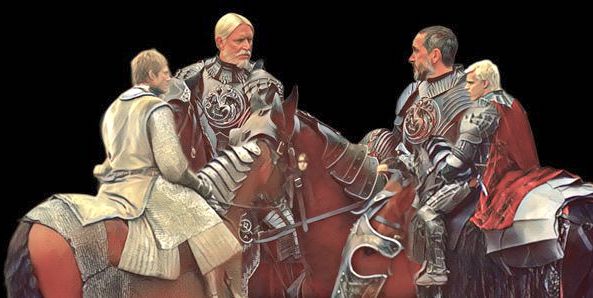

The production is equally impressive for how much it achieves with less. Far from the monumental budgets of Game of Thrones’ later seasons, the series relies on natural locations, weathered costumes, realistic cinematography, and intimate direction. The result is a tangible, almost historical Westeros where armor looks heavy and every journey exhausting. Instead of spectacle, the series offers immersion.

My only reservation is the score. It is competent and functional, but it lacks the emotional signature Ramin Djawadi gave the saga. The music of Game of Thrones did not merely accompany scenes; it defined the identity of the universe. In Knight, the score rarely rises beyond utility. There is no instantly recognizable theme, nothing that immediately evokes the series. This becomes especially clear in the rare moments when musical motifs associated with the larger franchise appear. In those instances, the audience response is immediate, as if the collective memory of the saga has been activated.

Even so, this detail does not undermine the whole. A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms succeeds because it understands exactly what it wants to be and never tries to compete with its predecessors in scale or spectacle. It expands the universe without inflating it, humanizes the story without simplifying it, and reminds us that the great tragedies of Westeros always begin with small decisions made by ordinary people.

By following Dunk and Egg along the dusty roads of the realm, we realize that dragons, thrones, and wars are only the surface. The true heart of this saga has always belonged to the people walking beneath them. By giving those characters center stage, the series not only honors Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, but it also deepens their legacy in a quiet, elegant, and profoundly human way.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.