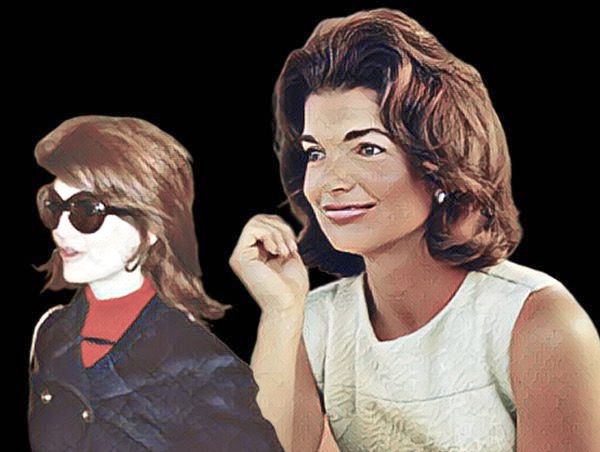

Few figures of the twentieth century remain as instantly recognizable as Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis. Decades after the assassination of John F. Kennedy and more than thirty years after her own death, Jackie still exerts a singular magnetism, as if she were simultaneously a real person and a mythological character. She was not merely an elegant First Lady nor simply the widow of a murdered president, but a figure who condensed beauty, symbolic power, vulnerability, and strategic self-control into a combination that is almost impossible to reproduce.

A revealing detail from Jackie’s early life helps explain why she was never simply a well-dressed woman swept along by history. Before becoming one of the most photographed women on earth, Jacqueline Bouvier worked in Washington journalism as a reporter and photographer, walking the streets with a camera, interviewing ordinary people, and crafting small narratives from fleeting encounters. This seemingly modest experience illuminates the woman she would become. Jackie learned how to observe, edit, frame reality, and create meaning through selection and omission. She would not only be photographed. She understood from the inside how public attention operates.

Her student years in Paris were equally formative. Away from rigid academic structures, she refined the ability to produce an intentional impression and to invent herself into a character while maintaining control over the narrative. What later appeared as aloof elegance may have been disciplined emotional management. She was not distant because she lacked feeling, but because she understood the cost of being consumed by the public gaze.

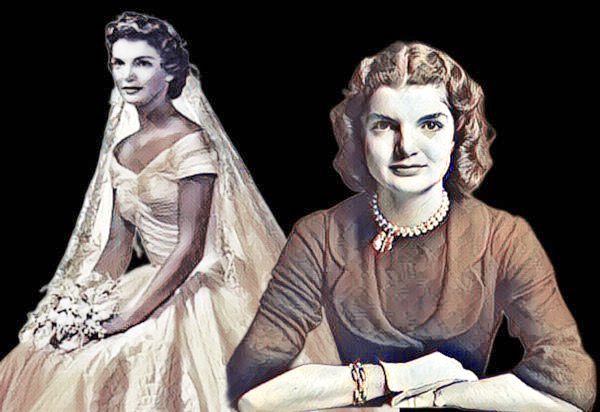

Born in 1929 into an American elite family, Jackie grew up surrounded by privilege and strict expectations regarding behavior and appearance. Intelligent, cultured, and multilingual, she cultivated interests in literature, art, and history that far exceeded the ornamental role assigned to women of her class. Her destiny changed when she met the young senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy, heir to a political dynasty, acutely aware of the importance of image. Their 1953 marriage united two power narratives and placed Jackie at the center of a carefully constructed political project.

The public image of the couple resembled a modern fairy tale, yet their private life was far from idyllic. Jackie endured miscarriages, the death of a newborn son, and the silent humiliation of JFK’s persistent infidelities, widely known within Washington’s political circles. Among these affairs, his relationship with Marilyn Monroe assumed almost mythic proportions because it threatened the presidency’s carefully cultivated aura of elegance and stability.

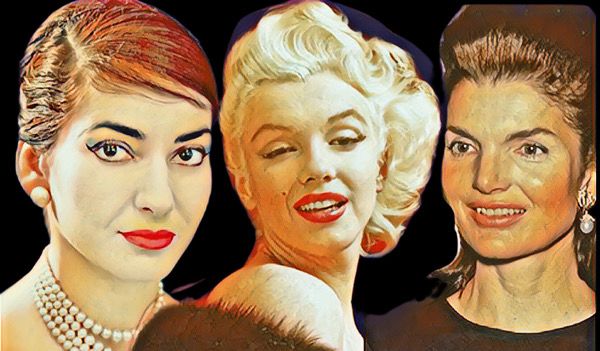

This tension reached a symbolic peak at Kennedy’s forty-fifth birthday celebration in 1962, which Jackie refused to attend because Marilyn would be present. The event gathered, almost theatrically, other central figures in this drama. Maria Callas, then Aristotle Onassis’s companion, opened the celebration with her legendary voice, while Marilyn Monroe closed it with her sensual rendition of “Happy Birthday,” one of the most iconic moments in American popular culture. The fact that Marilyn deeply admired Callas lends the scene an operatic quality, as if these women orbited the same emotional center without ever directly confronting one another.

Months later, JFK’s assassination transformed Jackie into a symbol of national mourning and composure under unimaginable pressure. The image of the young widow still wearing her blood-stained suit became one of the most powerful of the twentieth century, representing not only personal grief but the loss of a nation’s innocence. It was also during this period that Aristotle Onassis entered her life definitively, offering protection and security at a moment of extreme vulnerability.

Her marriage to the Greek shipping magnate in 1968 shocked much of the American public, which expected the presidential widow to remain an untouchable guardian of Camelot’s memory. For some, she had traded a pedestal for luxury. For others, it was an act of survival by a woman exhausted from living under constant threat. The fact that Onassis left Maria Callas to marry Jackie transformed the story into an emotional triangle worthy of classical tragedy.

Widowed again in 1975, Jackie reinvented herself as a book editor in New York and cultivated a sophisticated urban life alongside Swiss financier Maurice Tempelsman. Her relationship with her children, Caroline and John Jr., reflected both intense protection and rigorous control, particularly in the case of John Jr., whose existence symbolized the continuation of the Kennedy legacy.

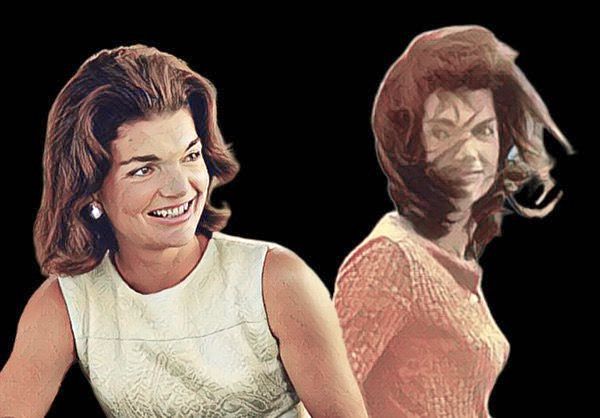

At the same time, she consolidated a personal aesthetic that redefined modern elegance. Her structured suits, pillbox hats, and oversized sunglasses functioned as visual armor, creating distance between herself and the world’s gaze. More than fashion, this style was a language of self-containment, projecting dignity while concealing vulnerability.

Jackie’s enduring place in the collective imagination can also be explained by her belonging to a lineage of women whose personal lives became global narratives. Grace Kelly and Diana, Princess of Wales, share with her extraordinary beauty, marriage to powerful men, and relentless media scrutiny. Yet Jackie distinguished herself through calculated opacity. While Diana connected with the public through emotional openness and Grace through fairy tale fantasy, Jackie maintained strategic distance, revealing only carefully curated fragments of herself. Her power resided in what she chose not to disclose.

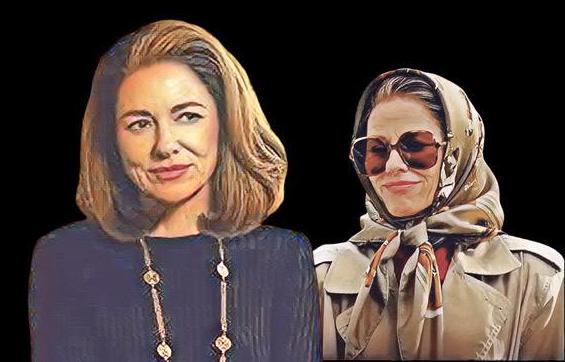

Each generation rediscovers Jackie through film and television, as if no single portrayal could ever be definitive. Natalie Portman’s performance in Jackie offered perhaps the most intimate and unsettling interpretation, focusing on the days after the assassination and on how Jackie actively constructed the myth of Camelot. Katie Holmes, in The Kennedys, emphasized the elegance and isolation of the young First Lady within a formidable political dynasty. Minka Kelly, in The Butler, presented a more luminous and classical version, while earlier portrayals, such as Roma Downey’s, highlighted the ceremonial public figure.

In The Crown, her meeting with Queen Elizabeth II is depicted as a collision between two distinct models of female power, glamour confronting monarchy with a mixture of fascination and restrained rivalry. In Love Story, Naomi Watts portrays Jackie with a complex blend of dignity and emotional intelligence, shaded by subtle touches of arrogance and by an unconditional devotion to her children that underscores her role as both matriarch and survivor. Future productions about the Kennedy family will inevitably return to her, because her story functions as both historical drama and modern myth.

The paradox is that the violence that shattered her personal life also made her eternal. The Jackie the world remembers was born at the moment when a young woman refused to erase the visible evidence of tragedy before millions of viewers. From then on, she ceased to be merely Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy and became a symbol of an era’s lost innocence.

Perhaps the world remains obsessed with Jackie because her story connects lives that feel almost mythological. JFK, Marilyn Monroe, Maria Callas, and Aristotle Onassis are not isolated historical figures but intertwined destinies whose choices produced emotional and symbolic consequences for all involved. To imagine how those trajectories might have differed is to imagine another version of the twentieth century itself.

Jackie Kennedy Onassis survived them all and became the inadvertent guardian of that shared memory. Her life demonstrates how fame, tragedy, and beauty can combine to create something more enduring than an individual biography. She was not simply an extraordinary woman in extraordinary circumstances but the embodiment of an era and proof that certain public figures never truly leave the stage.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.