John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr., the son of President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, has returned to the center of cultural attention with Ryan Murphy’s new series about his relationship with Carolyn Bessette Kennedy. Yet long before any television dramatization, his life already carried a symbolic weight that few people in history have had to bear. Since the assassination of JFK in 1963, he was seen as the living continuation of the Kennedy family and of the interrupted promise of the Camelot era. The image of the three-year-old boy saluting his father’s coffin during the state funeral became one of the most powerful photographs in American history, permanently fixing his position as the emotional heir to a grieving nation.

For decades, John-John was treated as an uncrowned American prince, someone expected to restore the Kennedy legacy in American politics. Cinematically handsome, educated, witty, and outwardly confident, he seemed to possess every quality required to fulfill that destiny. Yet adulthood revealed a man more hesitant than heroic, more human than mythic, someone living under constant tension between expectation and personal freedom.

His childhood was tightly controlled by Jackie Kennedy, who was determined to protect her children from the media scrutiny that had shaped her own life after her husband’s death. This protection ensured a degree of normalcy but also created an early awareness that he would never truly be anonymous. John grew up knowing he was watched even when no cameras were present, and this quiet sense of surveillance shaped his adult identity.

As an adult, he explored several paths without committing fully to any of them. He earned a law degree after academic struggles that were widely reported, a reminder that even his setbacks were public. Despite constant speculation that he would enter politics, he hesitated. Instead, he founded the political magazine George in 1995, an ambitious project that aimed to blend politics with popular culture and reinvent public discourse in the United States. The magazine became influential but faced financial and editorial challenges that prevented it from becoming a long-term success.

His personal life was followed with the intensity usually reserved for European royalty. His marriage to Carolyn Bessette Kennedy was celebrated as a modern fairy tale and as the union of two extraordinarily attractive figures, yet it quickly became a relationship under relentless siege from paparazzi and tabloids. Differences in temperament, external pressures, and the struggle to maintain privacy created instability, although friends reported genuine affection and attempts at reconciliation.

Comparisons with British princes arise almost automatically. Like Prince William, John carried the burden of continuity and stability. Like Prince Harry, he displayed impulses of escape and a desire to define himself outside institutional expectations. The crucial difference was that no formal institution existed to absorb his contradictions. He was heir to a political dynasty without an official role through which to express it.

The final months of his life appear less like those of a defeated man than those of someone profoundly exhausted. The terminal illness of Anthony Radziwill, his cousin and closest friend since childhood, represented an impending emotional loss of enormous magnitude. At the same time, George magazine faced serious challenges, his marriage was under strain, and public pressure for him to finally run for political office was becoming increasingly explicit.

Describing him as professionally unsuccessful would be misleading. He had created an influential publication and remained young by the standards of American public life. Nor is there evidence that he was on the verge of announcing an inevitable candidacy. What emerges from the most reliable accounts is the portrait of a man suspended between possibilities, aware that any decision would redefine not only his own life but also the symbolic future of the Kennedy dynasty.

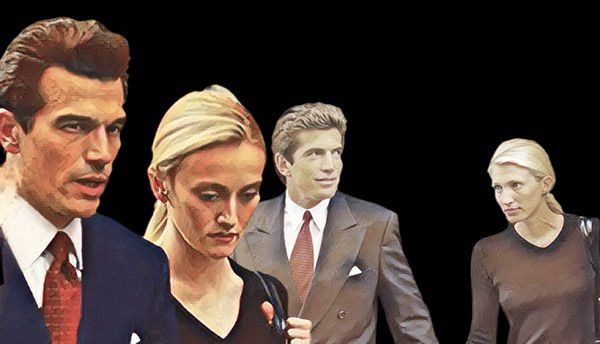

It is in this context that Ryan Murphy’s contemporary interpretation becomes particularly revealing. In his series about John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, called Love Story, Murphy moves away from the narrative of a fairy tale abruptly cut short and instead explores the slow erosion of a relationship lived under constant public scrutiny. The couple appears not merely as glamorous icons of the 1990s but as two individuals struggling to preserve intimacy in an environment that transformed every gesture into spectacle. Their love is portrayed as genuine yet persistently strained by personal differences, external expectations, and the weight of the Kennedy name.

Murphy has emphasized an empathetic and respectful approach, highlighting the human reality behind the iconic images. Rather than a sudden collapse, the story suggests a gradual process of compression, as if the couple were being squeezed by forces larger than themselves. This interpretation aligns with contemporary accounts of John’s final months, which depict not a defeated man but one emotionally drained by a lifetime lived under public observation.

His death in July 1999, in a plane crash off Martha’s Vineyard, became one of the most traumatic events in modern American memory and reinforced the perception of a recurring tragedy within the Kennedy family. The aircraft crash also killed Carolyn Bessette Kennedy and her sister Lauren, abruptly ending the life of a man who, at thirty-eight, still seemed like an unfinished project.

The paradox of John F. Kennedy Jr. is that he passed through history without leaving a political legacy comparable to that of his father, yet he remains one of America’s most enduring cultural enigmas. He symbolizes both the continuation of Camelot and its impossibility, embodying the idea that some lives are defined not by what they accomplish but by what they might have become.

Perhaps the lasting fascination with John-John lies precisely in this absence of resolution. He was neither a fully realized hero nor an isolated tragic figure, but a man caught between unrealistic expectations and private desires, between inheritance and identity, between national myth and ordinary human experience. Like a prince in a republic, he lived without a clear kingdom and died before deciding whether he even wanted one.

More than a political symbol, he remains an open question about what the United States expected of itself at the end of the twentieth century. Not merely the son of an assassinated president, but the mirror of a collective nostalgia for a future that never arrived.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.