For decades, the red carpet was merely the antechamber to the ceremony, an elegant corridor where stars paraded in gowns polished enough not to distract from what supposedly mattered: the films. Today, it is a stage of its own, a parallel spectacle in which the battle for attention, influence, and money begins hours before any envelope is opened. Somewhere between classic Hollywood glamour and global digital culture, the red carpet stopped being a formality and became a full-scale fashion show with enormous economic implications for everyone involved.

If one must identify a symbolic turning point at the Oscars, it has a name, a date, and a very specific color: Nicole Kidman, 1997, wearing Dior Haute Couture designed by John Galliano. The chartreuse green gown, embroidered and inspired by Eastern references, felt almost provocative against the safe, predictable aesthetic that had long dominated the ceremony. It was not merely elegant; it was conceptual. It did not aim to please everyone but to be remembered. The choice transformed the red carpet into a genuine fashion conversation rather than a celebrity footnote and placed European haute couture at the center of a ceremony traditionally ruled by custom American glamour. Many editors and fashion historians regard that moment as the true ground zero of the modern red carpet, when the Oscars began to engage directly with the global fashion industry.

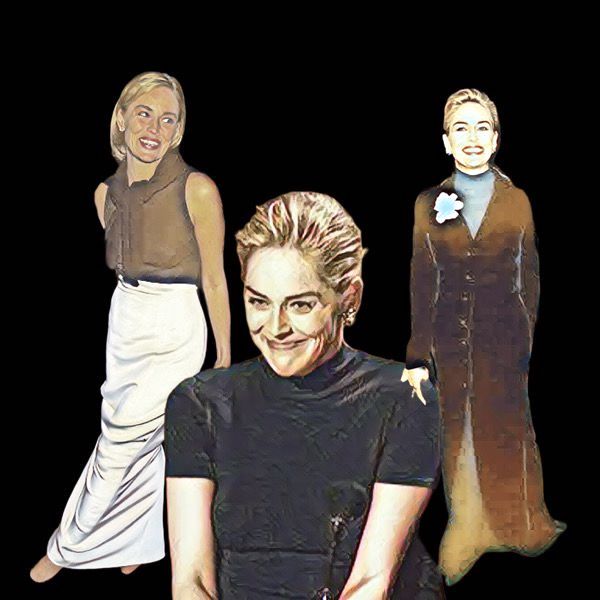

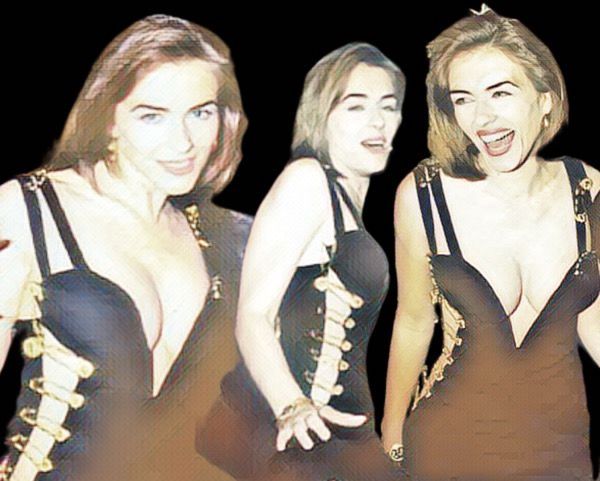

The shift, of course, had been building beforehand. In the 1990s, moments such as Elizabeth Hurley’s Versace safety-pin dress had already demonstrated the power of a look capable of dominating international headlines. Madonna turned the carpet into a performance, Winona Ryder popularized vintage, and Sharon Stone subverted expectations by pairing haute couture with a simple Gap shirt. These isolated gestures proved that audiences responded to boldness. What Kidman did was consolidate all of it into a single moment of planetary reach, inaugurating a logic that would never be abandoned.

From then on, the transformation accelerated through global television, the internet, and above all, the realization by major maisons that dressing an Oscar nominee amounts to purchasing the most efficient advertising campaign in the world. When millions watch the arrivals simultaneously, and the images continue to circulate for days — now for weeks — across social media, the gown stops being wardrobe and becomes strategy.

It was also during this period that the stylist emerged as a kind of personal brand director, responsible not merely for selecting clothes but for constructing a visual narrative aligned with awards campaigns, public persona, and commercial contracts. Today, figures such as Danielle Goldberg, Law Roach, and Kate Young operate with the influence of executive producers of image.

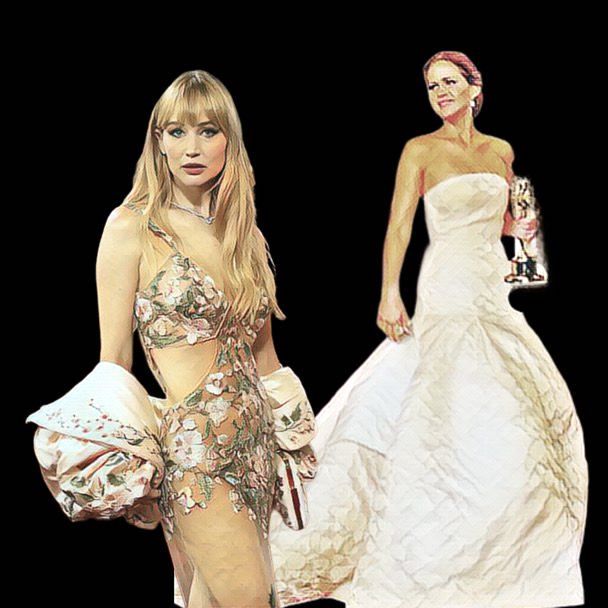

A recent feature on Jessie Buckley illustrates this mechanism with unusual clarity. As soon as she became an Oscar frontrunner for Hamnet, the actress hired — or rather, was equipped by the studio with — an elite stylist. This is not indulgence; it is investment. A single major red-carpet appearance can earn an actress between $50,000 and $250,000 simply for wearing a particular brand. An ambassadorship deal, meanwhile, moves into the millions. Jennifer Lawrence, for instance, reportedly received about $15 million for a three-year agreement with Dior. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that some careers are sustained as much by fashion contracts as by film salaries.

For the brands, the return comes in a more diffuse but equally powerful form. The industry calls it the halo effect: the image of a star in haute couture generates an aspirational aura that translates into sales of accessible products such as perfume, makeup, and handbags. No one needs to buy a $100,000 gown to participate symbolically in that glamour. A lipstick from the same house will do. It is emotional advertising on a global, instantaneous scale.

The result is that the red carpet has fragmented into aesthetic “tribes,” almost like living editorials. There is the classic glamour of the so-called Golden Age, dominated by houses such as Armani Privé or Versace Atelier, evoking old Hollywood. There is contemporary minimalism associated with brands like Louis Vuitton, favoring clean lines and architectural modernity. And there is the realm of calculated risk — sheer fabrics, daring silhouettes, runway references — where Dior and Chanel often lead. Each choice communicates something about the actress: tradition, audacity, youth, power, cultural relevance.

In this context, a gown is no longer simply beautiful or not. It becomes narrative. An actress who dominates the red carpet throughout the season builds a continuous media presence, reinforces her image as a leading figure, and often fuels a sense of inevitability around a potential win. The award still depends on Academy voters, but the symbolic atmosphere is shaped there, in front of the photographers.

Perhaps that is why the modern red carpet resembles Gladiator more than Cinderella, as the article suggests. It is not an innocent ball but an arena where armor made of silk, tulle, or velvet is chosen to defeat the competition. Glamour still exists, but it is calculated, strategic, and deeply intertwined with money, power, and public narrative.

In the end, cinema remains at the heart of Oscar night. But to reach it, stars must first cross this global runway where fashion and entertainment have become indistinguishable — and where, ever since that unforgettable appearance by Nicole Kidman in 1997, the outfit can speak just as loudly as the film itself.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.