Seventy years after its premiere, completed on February 16, 2025, Carousel remains one of the strangest and most profound musicals ever produced by Hollywood. Not because it lacks grandeur, romance, or memorable songs, but because it refuses to offer comfort. Unlike virtually all the other major titles of the Golden Age, this is a musical about failure, violence, guilt, and belated redemption. It is also a love story when love does not save anyone in time.

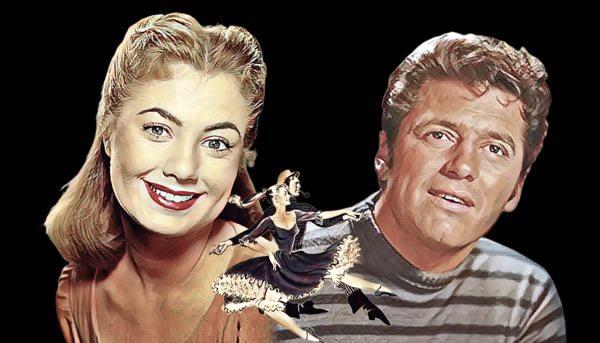

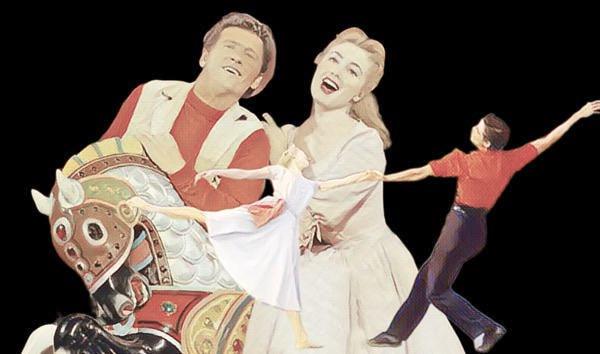

Directed by Henry King and starring Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones, the film adapts the Broadway musical created by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II in 1945, itself inspired by Ferenc Molnár’s 1909 play Liliom. The cinematic version preserves the moral ambiguity of the original work, something exceedingly rare for the genre. But there is a fascinating detail in the credits that often goes unnoticed: the screenplay was written by Henry and Phoebe Ephron, the husband-and-wife writing team who would later also be remembered as the parents of Nora Ephron.

This creative lineage is revealing. Long before Nora redefined the modern romantic comedy, her parents were already working within the classical Hollywood system, adapting one of the most painful love stories in musical theater. There is something almost ironic in that: the future author of witty, urban romances descends from a text about a man incapable of saying “I love you” while he is still alive.

A story that begins after death

The film’s narrative structure also defies convention.

The story begins after the protagonist’s death. Billy Bigelow has been dead for fifteen years and, standing outside the gates of Heaven, finally decides to accept the chance to return to Earth for one day. He had refused this opportunity before, but now he knows there are problems with his wife Julie and with the daughter he never met. Before descending again among the living, he must convince a celestial gatekeeper that he deserves permission, and it is while recounting his story that the film plunges into flashback.

Billy and Julie met when he worked as a carousel barker, both insisting they did not believe in love or marriage. They married anyway. Fired by the carousel owner, who was jealous and wanted him to remain single to attract customers, Billy ends up living off his wife’s family, unable or unwilling to take jobs he considers beneath him. His desperate attempt to prove he can provide leads him into a botched robbery with a criminal accomplice, Jigger Craigin, a decision that results in his death. Returning to Earth, he hopes not only to help his child but finally to express to Julie what he could never say in life.

Broadway: a daring success for a traumatized audience

When it opened on Broadway in April 1945, Carousel was already seen as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s most complex work. It is not the most popular, nor the most frequently revived, nor the most luminous. Paradoxically, it was the one most cherished by its creators, especially Rodgers, who always maintained it was his finest score. Seventy years after the film’s release, the work remains an outlier in American musical theater: grand in form, devastating in content, and strikingly modern in its psychology. The original production ran for about 890 performances at the Majestic Theatre, a remarkable achievement for such an emotionally heavy piece.

Postwar audiences recognized something deeply familiar in the story: the attempt to rebuild life after irreparable losses. The show consolidated the model of the “integrated musical,” in which dance and music function not as ornament but as dramatic narrative. That DNA was preserved in the film adaptation, perhaps even intensified.

Classics such as “If I Loved You” and “You’ll Never Walk Alone” became more than standards; they are true anthems that stand on their own beyond stage or screen, resonating across generations.

Hammerstein used to say that Carousel was “a story about ordinary people who make irreparable mistakes.” That definition explains why the show never fit comfortably within escapist entertainment. The music does not soften the narrative; it deepens it.

Unlike many of their other works, Carousel was not conceived as a collection of independent numbers. The score functions almost like a popular opera, with recurring motifs and continuous dramatic progression.

“If I Loved You” is the most famous example. It is not a direct declaration of love but a duet of evasions, two people unable to admit what they feel. Musically, it alternates spoken and sung passages, an innovation on Broadway in the 1940s preserved in the film.

“Soliloquy” is a rare tour de force for a male protagonist. Billy imagines the future of his unborn child, assuming it will be a boy, only to realize it might be a girl. The tone shifts from bravado to tenderness and finally to fear that he may not be able to protect her. Few musical theater songs expose masculine vulnerability so frankly.

“A Real Nice Clambake” has a curious origin: it was originally written for Oklahoma! and cut, then repurposed here with a new dramatic function. “June Is Bustin’ Out All Over” provides the show’s sunlit counterpoint, a burst of collective joy that makes what follows even more painful.

And then there is “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” perhaps the duo’s most transcendent song. It is neither romantic nor narrative but spiritual. Within the story, it offers consolation in the face of death and loss. Outside it, it has become a universal hymn of resilience, sung in stadiums, ceremonies, and moments of collective mourning.

Louise’s ballet: psychology through dance

At the emotional center of the film lies Louise’s ballet, featuring Billy and Julie’s daughter. The sequence runs approximately 12 to 13 minutes on screen and is one of the first major fully psychological narratives told entirely through dance in a Hollywood musical, precisely because it functions as an autonomous piece within the story. Before this, dance numbers typically served as decorative spectacle or technical display, only loosely tied to character development.

Without dialogue, the ballet depicts adolescence marked by social shame, loneliness, and the emotional legacy of an absent father. It is choreography as trauma: the body expresses what language cannot.

The sequence originates in Agnes de Mille’s groundbreaking choreography for the Broadway production, which introduced the concept of dramatic ballet to American musical theater. In the film, it acquires an almost dreamlike quality, blending memory and fantasy with imagery of the amusement park, a visual echo of Billy’s interrupted life.

De Mille had first developed the “dream ballet” in Oklahoma!, a sequence expressing inner desires and conflicts, common in classical ballet. In Carousel, she pushed that concept into darker, more mature territory.

This is what makes the sequence extraordinary. It is not an interlude but a revelation.

Behind the scenes: Sinatra walked away

Few productions of the era had such a turbulent process.

Frank Sinatra was originally cast as Billy Bigelow and even recorded the songs, but withdrew before filming was completed when he learned that scenes might need to be shot twice, once for standard CinemaScope and again for the experimental CinemaScope 55 format.

Later, more sensational stories claimed he left to join his wife, Ava Gardner, who was filming Mogambo in Africa. Shirley Jones later recounted that Gardner allegedly demanded his presence and hinted at an affair with Clark Gable, who, in fact, was involved with Grace Kelly during the shoot. Supposedly obsessed with Gardner, Sinatra flew out immediately, leading to Gordon MacRae’s emergency casting.

The more plausible explanation, confirmed by Sinatra himself, was technical. He was even sued by the studio for breaching his contract. The reality, as so often, is less dramatic but more revealing of the industry’s workings.

Sinatra had wanted the role for years. When finally offered it, he agreed on the condition that filming would not conflict with other commitments. Upon arriving in Maine and learning that scenes might need to be duplicated for two formats, he refused.

He later explained: “The Carousel deal happened suddenly… When I got to Maine, they sprang this crazy idea on me. I just don’t work that way.” He described the process as artistically and technically unworkable: “It would mean shooting a scene, relighting everything, changing marks, and doing it all over again… five or six extra weeks of work.”

He insisted he had not lost interest: “I had wanted to do Carousel for seven years. It broke my heart.” He also rejected the notion of ego: “Money wasn’t the issue… they were paying me well. And you can’t keep the money if you don’t work.”

Gordon MacRae later said the change did not surprise him. He suspected Sinatra might withdraw and had informed producer Darryl F. Zanuck he was ready to step in at any moment. He even refused to cut his hair after finishing Oklahoma! and kept himself prepared, performing the role in a summer production at the Texas State Fair as if anticipating the call.

Ironically, the technical team soon discovered a way to film both formats without duplication, but too late to bring Sinatra back.

Hollywood lost a potentially darker, more ambiguous Billy, but gained a legend. As with many stories from classical cinema, the dramatic version endured better than the plausible one.

Why Judy Garland did not star

Judy Garland was also seriously considered for Julie Jordan, a casting that now seems both ideal and unlikely. Ideal because few performers embodied vulnerability and strength with such intensity. Unlikely because by the mid-1950s, she was viewed as a financial and logistical risk after years of studio conflicts, delays, and health issues.

Her triumphant comeback in A Star Is Born reaffirmed her talent but also highlighted a difficult production process. Fox wanted stability, especially for a technically demanding project. Producers also sought a younger, more pastoral innocence for Julie, which Shirley Jones provided.

Garland represented the MGM era; Jones represented the new widescreen musical aesthetic. The choice signaled a generational shift.

Imagining Garland (and Sinatra) singing “If I Loved You” or “You’ll Never Walk Alone” suggests a different film, likely darker and less lyrical. Hollywood chose apparent purity over emotional volatility.

Modest box office, triumphant soundtrack

Commercially, the film’s reception was mixed. Critics praised it, but it did not match the box-office success of contemporaries like The King and I, released the same year. The soundtrack, however, became a national bestseller, and the film itself has since achieved classic status.

The film Hugh Jackman wanted to make

After the success of Les Misérables (2012), Hugh Jackman announced plans to produce and possibly star in a new film version. A script was completed, but the project stalled due to the difficulty of financing serious musical drama without guaranteed commercial appeal.

Perhaps inevitably so. Carousel demands empathy without absolution, lyricism without anesthesia. It is exactly the kind of work Hollywood admires but fears.

Why it remains a mega classic

Carousel endures because it does not fully belong to its genre. It has the scale of a musical but the structure of a moral tragedy. Billy is not a redeemed hero, Julie is not a passive victim, and the ending promises not happiness but the possibility of continuing.

Its emotional honesty feels strikingly modern. The film understands that love can coexist with violence, that remorse can arrive too late, and that the emotional legacy of a family does not vanish with death.

Seventy years later, the carousel keeps turning not as a symbol of childhood joy but as a metaphor for the human cycle of guilt, memory, and hope. Some classics survive because they make us dream. This one survives because it forces us to feel.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.