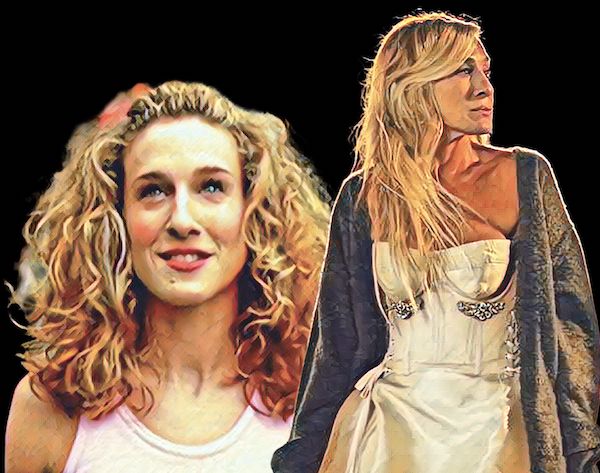

Freud might say I’m projecting — and maybe I am — when I spend these lingering moments trying to articulate how it feels as if, somehow, Carrie Bradshaw has been punished for the choices she made in life. It’s like reading a silent sentence written between the lines of the script. Not that I believe she deserves it, but (here comes the projection), it’s as if, after turning 50 and approaching 60, even being a widow doesn’t exempt her from proving (to whom, exactly?) that she’s worth less for being alone. She became a widow and a millionaire, yet “old” and “alone.” Unsurprisingly, we’re left grieving the absence of that vibrant woman who enchanted us for 25 years. The less-than-30-minute episode leading up to Carrie’s grand finale was nothing but nostalgia, sorrow, and deep questioning.

Since its premiere, And Just Like That has hovered over its characters with a sense of loss, emptiness, and doubt—especially Carrie, the only one of the four friends who married but never had children. That was a conscious choice she and Mr. Big made, never fully explored because, in her 40s, their life together was just beginning, and Carrie sought parties, dinners, and the freedom of a husband-boyfriend without anything to disrupt their chemistry. Samantha, out of the equation, never wanted marriage or motherhood; Charlotte always dreamed of husband and daughters—and got both; Miranda, who once didn’t care, was blindsided by surprise and ended up with a husband, a child, and now girlfriends. This rich, untapped material was always there in Sex and the City, yet it barely saw the light of day in the show’s four seasons.

From the moment Big’s unexpected death was announced, I said And Just Like That was about grief—about restarting when the energy and will to rediscover others have faded. I stand by that, but it makes the series darker than intended. In this episode, Carrie wrestles with Duncan’s absence, her editor’s blunt critique that her book (ending with a “widowed woman, alone at home”) is too depressing and won’t sell, and the discomfort of being questioned for living alone in a massive home. Before diving into it, I can’t help but wonder: why does she still have to follow someone else’s formula?

Carrie voices that question but agrees with the criticism. One of the most touching moments in the Sex and the City movies—whether the first or second, I think the latter—is when she and Big are subtly judged for having no children, the line being “it’s you and me, kid.” Yet no one imagines that phrase turning into “it’s only you, kid” a decade later. Not even the kitten eases the loneliness, because Carrie never emerged from her mourning.

For deeply personal reasons that only fiction makes grimmer, the series removed Mr. Big entirely from the narrative— the missing puzzle piece to understanding that Carrie’s soul left with him. The untamable Carrie of the 2000s only looks backward: she revisited Aidan and a love story that never worked in 22 years; she moved homes for him; now she longs for the apartment where she lived, trapped with her ghosts. The choice of Finneas’s For Cryin’ Out Loud! perfectly underscores the lessons she never learned.

Alone, rewriting the final chapter of her life story, Carrie must find a way to satisfy readers’ craving for a more uplifting ending. Will she manage?

Meanwhile, the stories around her echo the same dilemma: whether to accept or resist life’s offers. Charlotte and Harry have survived his health scare and, as always, face everyday domestic dramas. Yet something lingers: seeing Rock dressed and groomed like a girl, we realize Charlotte is swallowing her daughter’s choice, not fully accepting it. She doesn’t want Rock to be different, but her dream for her daughter was another. What will come of this?

Giuseppe, finally freed from his controlling mother, proposes to Anthony, who accepts—but Anthony, still haunted by the happiness shattered by his breakup with Stanford, is fearful.

Lisa Todd, irritated by Herbert’s lingering depression after losing the election, remains self-centered and insensitive. She flirts with her editor and repeats Miranda’s pattern: blaming her partner for her near cruelty. “Since when is it always about them?” she asks. And when did it stop being about her? I don’t like her—and thankfully, she’s leaving next week.

Seema and Adam continue their happy, uncomplicated romance. They offer the hope for a happy ending—and that comforts me.

Clueless Miranda presses on: without Brady’s consent or knowledge, she invites the future mother of his child to Thanksgiving, causing him to lose it upon discovery. Their fight, in front of Joy, only gives the British journalist a second reason to flee that intense, chaotic, and unstable relationship named Miranda Hobbes.

Yes, all that in less than 30 minutes. Next week promises Miranda’s Thanksgiving disaster (with everyone trying to bail), Charlotte searching for a boyfriend for Carrie (and failing). I’ve already said what I think will happen: Carrie no longer loves New York—and next week, she’ll say goodbye to the city for good.

Maybe she’ll move to London, maybe nowhere at all. But what matters is that, for the first time in 25 years, Carrie Bradshaw will cease to be the woman we knew—and we don’t know who will be waiting on the other side of the door she closes.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.