We are so starved and anxious that a handful of frames — barely adding up to a minute — are being dissected in detail as we try to imagine what lies ahead in the fourth season of House of the Dragon. In HBO’s year-end trailer, the images do not disappoint, because the message is clear from the very first seconds: the war has entered an irreversible phase.

The juxtaposition of Corlys Velaryon’s voice — grave, strategic, almost resigned — with the image of Alicent standing before Aemond on the Iron Throne immediately establishes the season’s dramatic axis. This is not simply about who occupies the throne, but about who understands the cost of occupying it. The scene suggests a point very early in the season’s chronology: before Harrenhal, before the effective seizure of King’s Landing, when calculation still exists, hesitation is still possible, and choices have not yet hardened into inevitability.

Alicent, in particular, is an especially eloquent presence in these images. She is no longer wearing Hightower green. The blue that appears in her costume echoes the Alicent who existed before the war — the woman she was before resentment hardened into political identity. This is not merely an aesthetic decision; it prepares the ground for what the season seems to suggest: an Alicent physically present in the Red Keep, likely under Rhaenyra’s rule, reenacting — in a distorted and tragic form — the intimacy the two once shared in their youth. If this proves true, it would mark a significant departure from the book, but at this stage, the original text may serve more as a suggestion than a blueprint.

The battle imagery reinforces the sense that the series has no intention of softening the impact of the season’s opening. The Battle of the Gullet appears in fragmented yet brutal flashes: fire reflected on ship decks, maritime chaos, and the explicit promise that this will be the largest naval conflict ever shown in Westeros — and possibly the bloodiest. What once loomed as a threat at the end of the second season now materializes as imminent catastrophe.

Interspersed with these moments are glimpses of the Winter Wolves advancing into battle, drums setting the rhythm of a war that no longer belongs solely to the Targaryens. The images suggest narrative compression: distinct battles seem to speak to one another, as if the Dance of the Dragons were spiraling forward, with conflicts colliding rather than unfolding in orderly succession.

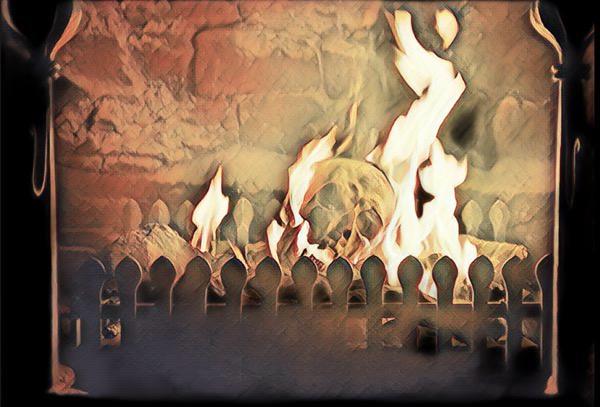

There is an image of a skull burning in a fireplace, and it is impossible to ignore. It is there to be interpreted, and honestly, everything points to it being Otto Hightower’s head. Not as an explicit spoiler, but as a symbolic construction. Otto has always been a power exercised far from the battlefield: the strategist, the political architect, the man who believed he could control war at a distance. This image visualizes the end of politics as a cold, calculated game. And yet — Otto ended the second season imprisoned in an unknown location, held captive by someone whose identity we still do not know. By whom?

The image gains even greater weight when read in dialogue with Ormund Hightower, who appears powerfully framed on a battlefield, played by James Norton. If Otto represents the House’s past — power exercised through influence, intrigue, and backroom maneuvering — Ormund emerges as its brutal present: the Hightower who goes to war. His stance before the Green army lacks any trace of subtlety. It is a direct summons to confrontation, most likely tied to the First Battle of Tumbleton. There is no calculation here, only inevitability. And we know he is destined to face Daemon.

The subtext is unmistakable: while Otto’s head likely burns in the fireplace — literally or symbolically — Ormund assumes the role of executioner. House Hightower trades the mind for the armed hand. Politics gives way to slaughter. And this reinforces the sense that the third season marks a definitive turning point: victory is no longer achieved through cunning, but through a willingness to endure horror to its very end.

One of the most loaded images is the strategy table, where figurines representing dragons are placed like expendable pieces. The shot anticipates Tumbleton not merely as a battle, but as a moral rupture. Committing multiple dragons at once signals betrayal, the collapse of loyalty, and deaths that permanently reshape the balance of the war. It is the moment when the series seems to say, without words: no one emerges unscathed. And yet, we still do not see any dragons.

Rhaenyra appears in images that blend conquest with isolation. Guards dressed in black draw their swords in the throne room, suggesting the reorganization of power after the fall of King’s Landing. The gesture is both political and symbolic: replacing the Greens, reconfiguring the guard, legitimizing rule not only through blood, but through presence. In another moment, she appears armed, wearing garments that evoke a queen under siege — almost a form of light armor, patterned like dragon scales. She is no longer merely the heir; she is a ruler preparing to fight for what she believes is her destiny.

That destiny returns explicitly in the image of Rhaenyra holding Viserys’s crown in her father’s former chambers. The framing is intimate, almost solemn. It closes a circle: the prophecy, the Valyrian dagger, the belief in the Prince That Was Promised. The season seems poised to argue that this faith — more than any army — may become one of the character’s greatest traps. In Westeros, prophecies exist, but they are rarely understood without cost. The series knows this. George R.R. Martin has always known it.

Daemon appears in an open field, armored, beside Oscar Tully, whose expression alone seems to capture the belated realization of someone who understands there is no way back. Everything suggests this will be the season’s final great battle, following Game of Thrones tradition: the penultimate episode as the apex of horror, the final one as the silence that follows, the accounting of losses.

Taken together, the images suggest a deliberate shift in perspective. If the second season ended with the sense that the Blacks held the advantage, the third works to restore uncertainty. Alliances fracture. Numerical superiority in dragons dissolves into betrayal. The war becomes less about winning and more about surviving what was done in the attempt to win.

Nothing in these images promises redemption. What they offer instead is consequence. And in House of the Dragon, consequence has always been the most merciless form of storytelling.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.