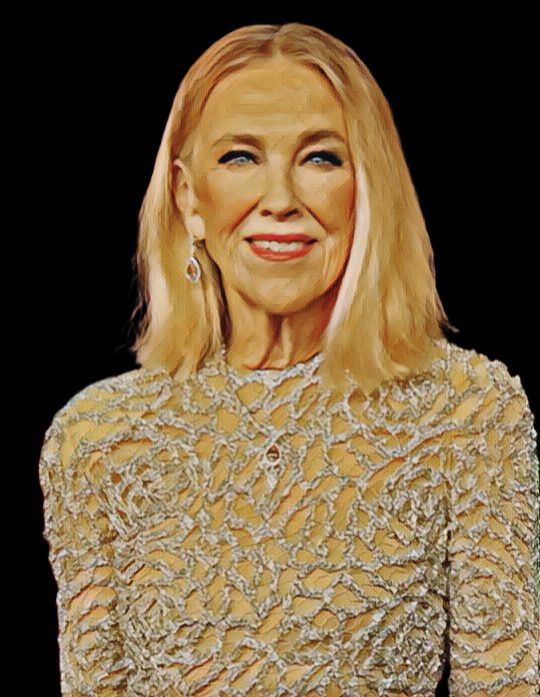

It’s hard to say what comes to mind first: the iconic scream of “Kevin!” in Home Alone, the unforgettable dance to Harry Belafonte in Beetlejuice, her priceless turn in the brilliant Schitt’s Creek, or the way she stole every scene in the recent hit The Studio. Catherine O’Hara’s comic genius was legendary, and her death at 71, following a brief and rare illness that has not been officially confirmed, brings to a close one of the most singular careers in contemporary comedy.

In a genre often associated with immediate laughter and fleeting impact, O’Hara built something far rarer: excessive characters, sometimes grotesque, almost always eccentric, yet deeply imbued with humanity, melancholy, and emotional intelligence. She was never merely funny. Above all, she was an actress who understood humor as a dramatic language.

Born in Canada, Catherine O’Hara emerged in the 1970s as one of the most inventive voices of the legendary SCTV, where she helped create and solidify a form of comedy rooted in improvisation, satire, and absurdity as tools of cultural critique. It was there, too, that a decisive partnership for her career was forged: her encounter with Eugene Levy, with whom she would go on to build, over decades, one of the most sophisticated collaborations in North American comedy. Together, they developed a language in which exaggeration never erased emotion, and ridicule never excluded dignity.

Her entry into American cinema came in the 1980s, through roles that brought her closer to Hollywood, including After Hours, directed by Martin Scorsese. In Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice, she definitively demonstrated her ability to turn excess into an aesthetic language, a role she would revisit decades later in the sequel released in 2024. In Home Alone, she became part of the emotional memory of generations by playing the desperate mother who crosses the world to reunite with her son—a seemingly simple figure, but one charged with emotional tension, guilt, and urgency.

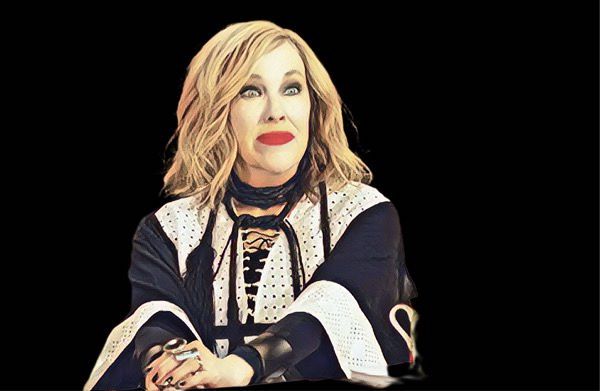

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, she deepened her artistic identity in Christopher Guest’s mockumentaries, such as Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show, and A Mighty Wind, consolidating a style built on eccentric, ridiculous, and profoundly human characters. On television, she appeared in series like Six Feet Under, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and 30 Rock, before achieving definitive recognition as Moira Rose in Schitt’s Creek, created by Eugene Levy and his son Dan Levy.

Moira synthesizes O’Hara’s legacy: aristocratic and pathetic, arrogant and vulnerable, ridiculous and tragic. Through the role, O’Hara won an Emmy and the kind of late-career consecration that often comes only to artists who endure without ever relinquishing their singularity. Her partnership with Levy reached its apex there, turning Johnny and Moira Rose into one of the most complex and emotionally resonant portrayals in contemporary comedy.

In recent years, her presence remained both relevant and symbolic. She earned an Emmy nomination for The Last of Us and appeared in The Studio, a sharp satire of Hollywood’s inner workings, reaffirming her affinity for narratives that dismantle the spectacle of the entertainment industry itself—as if her entire career had been, from the beginning, an ironic commentary on the system that celebrated her.

Over more than five decades, Catherine O’Hara moved seamlessly between auteur cinema, Hollywood mainstream, and prestige television, always with the same signature: characters that seemed larger than life, yet revealed something profoundly human. Her talent never lay in easy laughs, but in her ability to expose, beneath excess, fear, desire, fragility, and loneliness.

Off-screen, she lived far from the spotlight. She had been married since 1992 to production designer Bo Welch, with whom she had two children. According to the New York Post, paramedics were urgently called to the actress’s home and transported her to a nearby hospital, but she died hours later. The newspaper reports that O’Hara lived with a rare congenital condition called dextrocardia with situs inversus, in which the organs of the chest and abdomen are positioned in reverse relative to standard anatomy. It is not clear, however, whether this condition had any connection to her death.

Catherine O’Hara leaves behind not only an iconic filmography but an idea of comedy that resists time, less as a genre than as a way of seeing the world. Perhaps that is her greatest legacy: proving that humor can be profound, political, melancholic, and unforgettable, without ever losing its power to make us laugh.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.