While he was alive, in an already homophobic Russia, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky hid being homosexual and eventually got married on impulse to bury the already obvious suspicions. The chosen one was the young Antonina Miliukova, who for many years was known as a neurotic and nymphomaniac. She ended her days in the hospital like a madwoman. Today, Antonina’s role in Tchaikovsky’s life is no longer seen in the one-dimensional terms that tarnished his memory, even though, in fact, her existence contributed to worsening the composer’s psychological and physical state.

This tragic story always put Antonina negatively, and not even her account was taken seriously, having been labeled as the product of a reckless and insane woman. In the 1971 film, The Music Lovers the director Ken Russell brought an excellent Glenda Jackson in the role of the unhappy young woman, and Richard Chamberlain as Tchaikovsky. Now, 51 years later, the Cannes Festival brings a daring Russian production that dared the repression of its country to tell the story of one of its heroes, who happened to be gay. This trajectory and all the toxicity of the couple’s unhealthy relationship is the theme of the film Tchaikovsky’s Wife, which opened the festival in 2022

Directed by Kirill Serebrennikov, the production faced censorship at the hands of its national government and tells the story of Antonina as the composer’s devoted but renegade wife. For the director, more than an unhappy love story, it is a metaphor for other forms of resistance to authority.

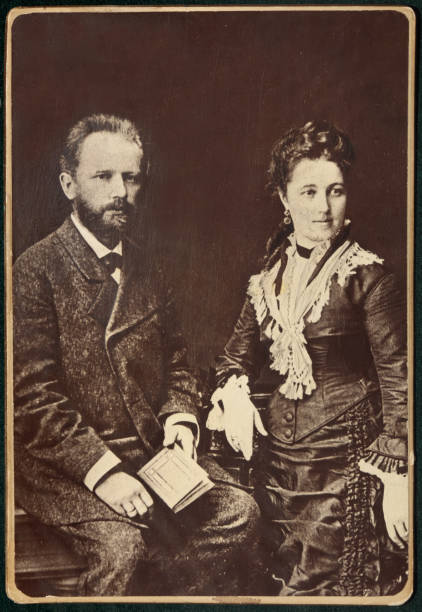

Revised now, Antonina is portrayed as a woman so sincerely in love with her idol that she accepts being a part of the farce that cost her mental health. Played by Alyona Mikhaylova on screen, the reality is different. Historians confirm that the young woman met Tchaikovsky in 1865, 12 years before they were married, through a mutual friend, the singer Anastasia Khvostova. Aged just 16 at the time, she fell in love with internationally famous Tchaikovsky (in the current film, played by Odin Biron), who was 25 at the time. The impact of that first contact was never remembered by him, but Nina, as they called her, became obsessed. She gave up her job as a professional seamstress to study music at the Moscow Conservatory of Music and take classes with him. With no money, the plan backfired, but in 1877, when she received an inheritance, she decided to send love letters to her idol and found that now things would have changed.

It’s just that at this point Tchaikovksy felt vulnerable to society’s criticism and in an impetus, he proposed marriage to Nina. Disaster announced. The composer was never in love with his wife, he disliked her simple origins and complicated family. In just six weeks they broke up. One of the great conflicts, today more than ever is clear, was the fact that she married and hoped to have a family, that is, to have sexual relations. For Tchaikovsky, the relationship would always be fraternal. By having relationships with other men, Antonina went down in history as a nymphomaniac. Not quite true.

The negative image of Nina, perpetuated for centuries, was also born from the description of the composer’s brother, Modest, who described her as a maddened idiot (sic), also based on reports from the musician’s friends, who were also concerned about signs of imbalance in Nina. Coming from a dysfunctional family, she spent her childhood in an unfavorable emotional environment. When she resumed contact with her future husband, in March 1877, it was immediately with a confessional love letter. Surprisingly, he responded and in just four encounters, proposed marriage, promising the bride only his “brotherly” love. It was the way he’d found to anticipate the truth, but Nina ignored it and accepted it, expecting a complete union. The fact that at the time this all happened the composer was working on the opera Onegin, one of his classics, to this day generates speculation that life imitated art. Bearing in mind that Tatiana wrote a love letter to Onegin, and it was rejected, it’s ironic to think that he was experiencing something similar in his personal life. According to his letters to his patron, Nadezhda von Meck, he made clear his sympathy for Tatiana and his desire to avoid “repeating” Onegin’s cruelty towards a woman who loves him. Be that as it may, he married without thinking and regretted it immediately. Even 20 days later, the marriage was still not consummated.

Repentant and “stuck” in marriage, Tchaikovsky had a nervous breakdown. He even asked his brother, Anatoly, and his friend, the composer Nikolai Rubinstein, to inform his wife that their separation was permanent. Nina, happy to be Tchaikovksy’s wife, reacted as if nothing was happening and the denial worried both men. This meeting is the main evidence against Nina, the fact that she didn’t react emotionally when she was informed of the end of the marriage.

In fact, Nina has always seen herself as the victim of a family conspiracy that has always rejected her. Furthermore, he considered that Tchaikovsky’s breakdown was caused by the anguish of being torn between his wife and his music. Maybe that could give hints to an unbalance.

Tchaikovsky undertook several attempts at divorce between 1878 and 1880, but to no avail, as for a long time, Antonina continued to believe in the possibility of some kind of future “reconciliation” and refused to go along with what her husband proposed, thus invoking his wrath, with accusations of stupidity, suspicions of “blackmail”, etc. It was not until 1881 that Tchaikovsky finally abandoned the idea of divorce. Nina went on to have sex with other men. She refused bribery attempts that were made to change her mind. Desperate, the musician even tried to kill himself by entering the frozen river in Moscow. Nothing shook Mrs. Tchaikovksy.

Although many have put the negative image of the obstinate wife, Tchaikovsky himself would have written to Nadezhda von Meck that Nina was innocent. “My wife, whatever she is, is not to be blamed for bringing the situation to the point where marriage became necessary,” he wrote. “It’s all my lack of character, my weakness, impracticality, childishness!” he admitted. However, with relatives and friends, he was less discreet and began to hate his wife, who he called a “reptile”, becoming hysterical when he received news from her.

Afraid she would make her secret public, especially as Nina was soon described as “unpredictable,” Tchaikovsky kept away from his wife, paying an allowance. Between 1881 and 1884 Antonina had three illegitimate children with Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Shlykov, a lawyer she had lived with since resigned that her husband had left her anyway. To this day, however, still under the narrative that she was a nymphomaniac, some claim that there were more males and that each child would have a different father and all were given up for adoption, but all three died during childhood.

The distant but frayed relationship came to an end with the musician’s sudden death at the age of 53, in 1893. Officially they allege that it was cholera, after accidentally drinking a glass of unboiled water. Others consider it to be suicide. Nina still lived 24 years, but very badly. Soon after the composer’s death, she began to show signs of emotional disturbance (persecution mania), and when it worsened, three years later, she was admitted to an asylum, where she stayed for 20 years, diagnosed with chronic paranoia. She died of pneumonia in 1917. Nina recorded her memories of the marriage in letters and documents that were never published, and where Tchaikovsky’s biographer, Alexander Poznansky, says that there was a memory of a “naive, superficial and not very intelligent”, woman, dedicated to the memory of her husband, still his unwavering fan.

In the film Tchaikovksy’s Wife, Serebrennikov bets on theatricality to revisit the drama, transforming the film, as critics warn, into “a terrifying tale of mental disintegration in its final act”. A tragic and still very current story.

2 comentários Adicione o seu