There are several clichés surrounding the figure of the ballerina, but if we were to follow the cinema, the world of dance is a crime scene deified on stage. With the arrival of the horror film Abigail in cinemas, they rescue the ethereal image of a dancer in a false facade of a murderous vampire. Calm down, Abigail is not a ballet film, but rather, it uses Tchaikovsky’s music for Swan Lake and the eternal duality of the work’s main roles – Odette-Odile – to reinforce the narrative of fear. Well, in cinema (including European cinema, it is not Hollywood’s privilege), the rigor of ballet is synonymous with pain and death. With violence.

The smile that hides the pain

A few years ago, the image of the ballerina’s feet gained legendary context with a photo that no one knows anymore who was the author of. One, with pointe shoes, and the other, injured and with blood. The image that reflects what dance is: Art and Beauty achieved with physical Pain, never seen on stage.

Add to these other challenging elements for mental health: the brevity of the career that depends on physique and youth; the physical type that needs to be light (that is, under excessive weight control); dealing with injuries (mild or serious, after all, the knee and feet are used in unnatural positions, not forgetting jumping) and the need for an artistic soul that includes interpretation and musicality, without forgetting an exact concentration needed to maintain the counts. It doesn’t help that the image of the teachers and choreographers was also marked by rigidity, aggressiveness, and arrogance, it really seems like ballet is a horror film.

This drama is irresistible to the imagination, literature, visual arts, theater, and cinema have helped to immortalize the image of this ethereal figure who is anything but what he seems. Partly because the world to this day is fascinated by the developed ability to dance on tiptoe, since 1831, when Marie Taglioni, as the sylph, “proved” that ballerinas were sylphs. The world was never the same again.

Backstage rivalry: a ballet classic

If you ask, all dancers will deny the cliché of rival dancers fighting for a chance to be the season’s principal, but if we look at history, it existed. Part of patriarchal culture? Without a doubt, it is undeniable that stories of enmity are more famous than those of sisterhood, although it has the same weight in the world of dance.

It was not an invention that Fanny Elssler was competing for audiences and roles with Marie Taglioni. Nor was it a lie that friends and fans chose whether Anna Pavlova was better than Tamara Kasarvina. The beloved Lynn Seymour never reached the popularity of Margot Fonteyn, in fact, several incredible dancers remained under her shadow, but it was Lynn who “lost” her main role to a more famous Fonteyn, even after having an abortion to continue dancing. My favorite was the day Mathilde Kschessinska let real chickens on stage to disrupt Olga Preobrajenska‘s solo at a performance of La Fille Mal Gardée because she considered her competition. With these true stories, the “legends” of putting glass inside sneakers to get “threats” out of the way was just a pirouette ahead, how could Cinema resist the cliché?

How does hierarchy impact the legend of the rivalry?

A dancer has always had defined characteristics in almost every film she stands out in: she is disciplined, she is a perfectionist, she is competitive, she is insecure, she is ambitious and she also feels the pressure of having to choose between her career and Love.

Yes, there are many hours of training and rehearsal compared to what you get in return. In a large company, if there are two productions a year (in Europe and the USA there are more), it is worth celebrating, but the season does not exceed two weeks, with a maximum of five nights. In other words, your years of training have rare opportunities to be put into practice, jealousy and envy behind the scenes are absolutely inevitable.

Join this account, the Ego. Dancing the classics is a constant dream, dancing them again too. And, within this, there is a dynamic of “hierarchy”. The choreographer chooses his dancer for the opening night and this definition is where the greatest prestige of any dance professional lies. This is the basis of the drama of Black Swan, for example, and developed with horror colors when we follow the impact that this fact has on the mental health of Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), who is panicked by the talent of her replacement (Mila Kunis). Therefore, over time, the dancer dreams and strives to lead a season, whether in classics or even better, in a new production. Anyone else who can take that away from her is naturally a rival.

Classical dance has had “fewer new ballets” for centuries, and when we say that we have to differentiate the “full length” of “symphonic”. The last one, immortalized by the genius of George Balanchine, is a choreography set to the music, highlighting the movement. “Full-length” works with a dramatic plot, which includes the cast’s acting skills in the production. These are rarer nowadays. In Russia, Yuri Grigorovich created some spectacular full-length ballets, but that was until the 1980s when he stopped. In Europe there are more choreographers still creating today, but the most famous who remain in memory and managed to create something still relevant are from the 1970s: Kenneth McMillan and John Cranko. I know professionals will argue with me that there are still ballets being created, Alexei Ramtansky is one of the active ones, but the historical impact doesn’t beat McMillan’s Romeo and Juliet or Manon or Cranko’s Taming of the Shrew and Onegin.

Neurosis highlighted through the Hollywood lens

With so many aspects of Dance, neurosis is the most common aspect that Cinema chose to define a dancer. From Limelight to Black Swan, entering a studio we know that the dancer necessarily has a tormented soul. The most iconic of these is perhaps Victoria Paige (Moira Shearer) in the best film ever made about a ballet company and the behind-the-scenes of dance.

Victoria is a talented young woman who rises to stardom in a prestigious company, gains notoriety, and finally has a ballet created for her, The Red Shoes. In other words, it combines training, ambition, discovery, prestige, and finally, stardom. However, she falls in love and in dancing there are some challenges: motherhood is not well regarded, or it wasn’t, being a choice that almost everyone would have to make: career or femininity.

The 1948 film takes us to follow the process of Vicky’s mental deterioration, who, faced with the impossibility of having both, chooses death. Everything about the film makes it one of the greatest works ever created for the screen, I can’t recommend it more.

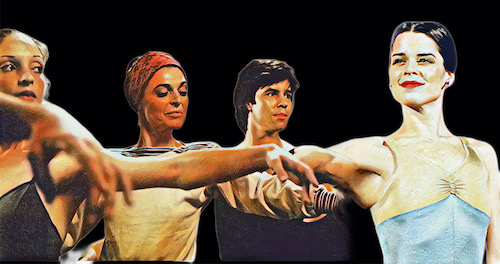

After him, there are other successes, but the best is still the 1977 film, The Turning Point, inspired by a true story and which, although it highlights the drama of the brevity of a dancer’s career (and the weight of her choices), shows the closest competitiveness to reality (there are no violent gestures or baseness, but envy and jealousy) and inspires the love of dance through the naivety and honesty of Emilia (Leslie Browne).

The Swan theme in horror films

For somewhat obvious reasons, the two main ballets of an artist’s career – Swan Lake and Giselle – reinforce the basis of negative dance clichés. The duality of Odette and Odile, and the madness of the betrayed peasant girl, are at the heart of the biggest recent dance film success: 2010’s Black Swan. Natalie Portman won the Oscar for Best Actress and the film is being adapted into a musical on Broadway. But what the film effectively did was forever solidify the “Swan Lake theme” as a horror one.

How is it possible in front of one of the most famous melodies of all time, yet emotional and romantic? Simply, Hollywood used her for Dracula. When Bela Lugosi immortalized the image of the vampire, it was to the sound of Tchaikovsky and since then, the dark and tragic soul of the composition has entered the popular imagination as a theme of pain, loneliness, and fear. Abigail also uses music for this reason. In the case of the 1931 work, the choice for classical music was simple: a way of reducing production costs and not paying for an original theme. Yes, vampire even in that, sucking its main source from ballet.

How to change the “bloody tutu” narrative?

In an excellent article published in the New York Times, journalist Margaret Fuhrer highlights the theme of this post, precisely questioning the connection between an ethereal art like classical dance and the horror genre. “For decades, film and television have wrung drama from the idea of the ballerina whose elegance on stage hides a terrible darkness,” she writes. “Sometimes this drama is anchored in the truths of ballet life: the search for impossible perfection, the bodily sacrifice required by a physical art. But sometimes these stories rely on broader clichés, using ballet as a beautiful canvas to splatter blood,” she adds.

I would say that the panic of pain and blood has a greater impact than talking about the risks of eating disorders (illustrated in Black Swan and Center Stage, but ignored in The Red Shoes or The Turning Point), or mental health. The problem is that, as Margaret also points out, today the most popular image is that of the “dangerous ballerina”, an unbalanced and violent sociopath (which generates the cliché known as “bloody tutu”, about the clothes that the ballerina wears in the stage), which is far from reality, is repetitive and predictable and does not help to address the most sensitive themes in the ballet universe. As she says, “The dangerous ballerina – as imagined on-screen and later in the popular imagination – is obsessed, tormented, and probably the “You will end up harming yourself or other people.”

Notice: popular imagination. It is already established. And the speech of Terry Gillet, one of the creators of Abigail, who in the article describes dancers as “dedicated, obstinate and powerful” people, but who “know how to hide all this” the mirror of professionals who are disguised in some way.

According to the NYT, Abigail takes a lot of inspiration from Black Swan to construct the vampire of the title, saying that the duality of the “transformation” of the white swan into black is not the story of Swan Lake, but the horror story created by Darren Aronofsky, not necessarily close to what happens behind the scenes. It is the wave that writer Adrienne McLean comments that cinema today reinforces the wrong idea that “ballet will make you lose your mind” and those ballerinas are potentially “crazy”. That’s not cool, not even in fiction.

If one day the drama of Vicky Paige’s choice was the reference, today mothers who hear their daughters dream of being ballerinas fear the “black swan” effect, iconized by Nina Sayers. Of course, as Abigail is a vampire – literally – the film is a “joke” that uses the image as a basis. Especially the “innocent-looking ballerina covered in blood”. Precisely what the sneaker photo inadvertently inspired.

Is there no other story to tell? After all, research data cited in the New York Times says that, in the United States, less than 2% of the population has even seen a ballet in their lives, that is, associating dancers with psychopaths and vampires does not seem to help popularize dance, but rather fuels more distortions and bad examples. My heart feels for this.